Humans have an innate knack for identifying food that is fit to eat. There’s a reason you instinctively enjoy fresh fruit and vegetables, but find maggot-infested rotting flesh offputting, for example. However, we like to automate as much of the food production process as possible so we can do other things, so it’s necessary to have machines sort the ripe and ready produce from the rest at times. [kutluhan_aktar] has found a way to do just that, using the power of neural networks.

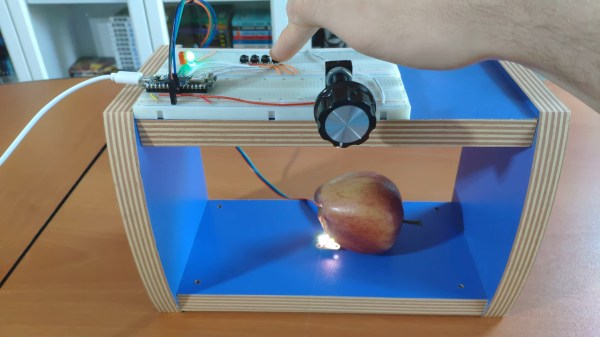

The project’s goal is a straightforward one, aiming to detect ripeness in fruit and vegetables by monitoring pigment changes. Rather than use a camera, the project relies on data from an AS7341 visible light sensor, which is better suited to capturing accurate spectral data. This allows a better read of the actual light reflected by the fruit, as determined by the pigments in the skin which are directly related to ripeness.

Sample readings were taken from a series of fruit and vegetables over a period of several days, which allowed a database to be built up of the produce at various stages of ripeness. This was then used to create a TensorFlow model which can determine the ripeness of fruit held under the sensor with a reasonable degree of certainty.

The build is a great example of the use of advanced sensing in combination with neural networks. We suspect the results are far more accurate than could have reasonably be determined with a cheap webcam, though we’d love to see an in-depth comparison as such.

Believe it or not, it’s not the only fruit spectrometer we’ve featured in these hallowed pages. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Detecting Ripeness In Fruit And Vegetables Via Neural Networks”