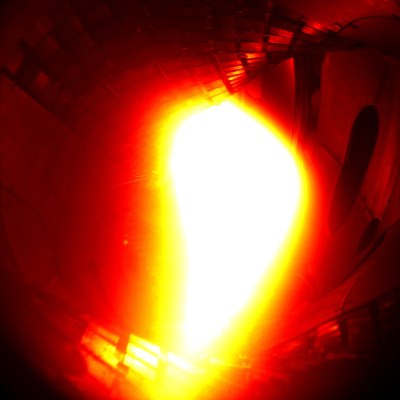

In nuclear fusion, the triple product – also known as the Lawson criterion – defines the point at which a nuclear fusion reaction produces more power than is needed to sustain the fusion reaction. Recently the German Wendelstein 7-X stellarator managed to hit new records here during its most recent OP 2.3 experimental campaign, courtesy of a frozen hydrogen pellet injector developed by the US Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory. With this injector the stellarator was able to sustain plasma for over 43 seconds as microwaves heated the freshly injected pellets.

Although the W7-X team was informed later that the recently decommissioned UK-based JET tokamak had achieved a similar triple product during its last – so far unpublished – runs, it’s of note that the JET tokamak had triple the plasma volume. Having a larger plasma volume makes such an achievement significantly easier due to inherently less heat loss, which arguably makes the W7-X achievement more noteworthy.

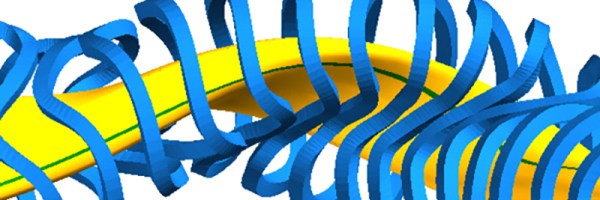

The triple product is also just one of the many ways to measure progress in commercial nuclear fusion, with fusion reactors dealing with considerations like low- and high-confinement mode, plasma instabilities like ELMs and the Greenwald Density Limit, as we previously covered. Here stellarators also seem to have a leg up on tokamaks, with the proposed SQuID stellarator design conceivably leap-frogging the latter based on all the lessons learned from W7-X.

Top image: Inside the vacuum vessel of Wendelstein 7-X. (Credit: Jan Hosan, MPI for Plasma Physics)