If you want to blink an LED once every second, you could use just about any old timer circuit to create a 1 Hz signal. Or, you could go the complicated route like [Anthony Vincz] and grab 1 Hz off a radio clock instead.

The build is an entry for the 2025 One Hertz Challenge, with [Anthony] pushing himself to whip up a simple entry on a single Sunday morning. He started by grabbing a NE567 tone decoder IC, which uses a phase-locked loop to trigger an output when detecting a tone of a given frequency. [Anthony] had used this chip hooked up to an Arduino to act as a Morse decoder, which picked up sound from an electret mic and decoded it into readable output.

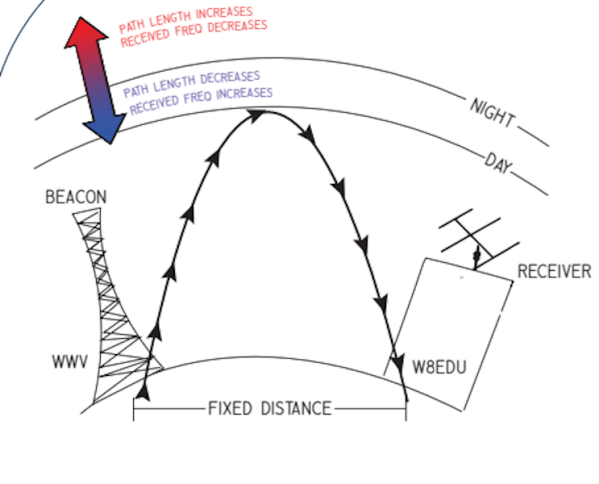

However, he realized he could repurpose the NE567 to blink in response to output from radio time stations like the 60 KHz British and 77.5 KHz German broadcasts. He thus grabbed a software-defined radio, tuned it into one of the time stations, and adjusted the signal to effectively sound a regular 800 Hz tone coming out of his computer’s speakers that cycled once every second. He then tweaked the NE567 so it would trigger off this repetitive tone every second, flashing an LED.

Is it the easiest way to flash an LED? No. It’s complicated, but it’s also creative. They say a one hertz signal is always in the last place you look.

Continue reading “2025 One Hertz Challenge: Blinking An LED With The Aid Of Radio Time”