Traditionally, capacitors are like really bad rechargeable batteries. Supercapacitors changed that, making it practical to use a fast-charging capacitor in place of rechargeable batteries. However, supercapacitors work in a different way than conventional (dielectric) capacitors. They use either an electrostatic scheme to achieve very close separation of charge (as little as 0.3 nanometers) or electrochemical pseudocapacitance (or sometime a combination of those methods).

In a conventional capacitor the two electrodes are as close together as practical and as large as practical because the capacitance goes up with surface area and down with distance between the plates. Unfortunately, for high-performance energy storage, capacitors (of the conventional kind) have a problem: you can get high capacitance or high breakdown voltage, but not both. That’s intuitive since getting the plates closer makes for higher capacitance but also makes the dielectric more likely to break down as the electric field inside the capacitor becomes higher with both voltage and closer plate spacing (the electric field, E, is equal to the voltage divided by the plate spacing).

[Guowen Meng] and others from several Chinese and US universities recently published a paper in the journal Science Advances that offers a way around this problem. By using a 3D carbon nanotube electrode, they can improve a dielectric capacitor to perform nearly as well as a supercapacitor (they are claiming 2Wh/kg energy density in their device).

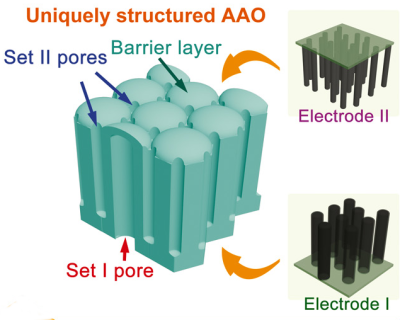

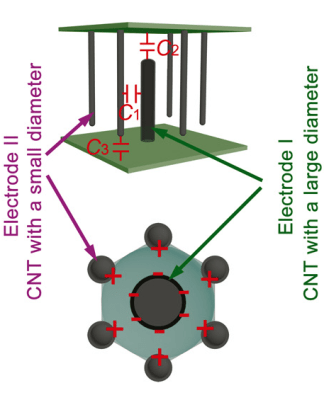

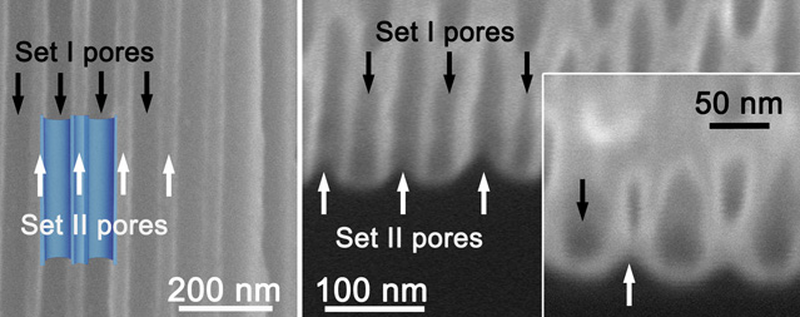

The capacitor forms in a nanoporous membrane of anodic aluminum oxide. The pores do not go all the way through, but stop short, forming a barrier layer at the bottom of each pore. Some of the pores go through the material in one direction, and the rest go through in the other direction. The researchers deposited nanotubes in the pores and these tubes form the plates of the capacitor (see picture, right). The result is a capacitor with a high-capacity (due to the large surface area) but with an enhanced breakdown voltage thanks to the uniform pore walls.

The capacitor forms in a nanoporous membrane of anodic aluminum oxide. The pores do not go all the way through, but stop short, forming a barrier layer at the bottom of each pore. Some of the pores go through the material in one direction, and the rest go through in the other direction. The researchers deposited nanotubes in the pores and these tubes form the plates of the capacitor (see picture, right). The result is a capacitor with a high-capacity (due to the large surface area) but with an enhanced breakdown voltage thanks to the uniform pore walls.

To improve performance, the pores in the aluminum oxide are formed so that one large pore pointing in one direction is surrounded by six smaller pores going in the other direction (see picture to left). In this configuration, the capacitance in a 1 micron thick membrane could be as high as 9.8 microfarads per square centimeter.

To improve performance, the pores in the aluminum oxide are formed so that one large pore pointing in one direction is surrounded by six smaller pores going in the other direction (see picture to left). In this configuration, the capacitance in a 1 micron thick membrane could be as high as 9.8 microfarads per square centimeter.

For comparison, most high-value conventional capacitors are electrolytic and use two different plates: a plate of metallic foil and a semi-liquid electrolyte. You can even make one of these at home, if you are so inclined (see video below).

We’ve talked about supercapacitors before (even homebrew ones), and this technology could make high capacitance devices even better. We’ve also talked about graphene supercaps you can build yourself with a DVD burner.

It is amazing to think how a new technology like carbon nanotubes can make something as old and simple as a capacitor better. You have to wonder what other improvements will come as we understand these new materials even better.

I’d venture a guess that similar technology could/will/already is being used in batteries for higher surface areas and such.

I’m not so sure I think batteries are still quite low tech I could be wrong though https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uI1eRy0uBI8

A —>”Lithium”<— polymer battery! And in the tear down, as the metal exposed to air oxidises and slowly turns from silver to black, he asks "I wonder if it is aluminium".

Here’s an infographic from the paper that shows where they are in relation to electrolytics and batteries:

http://d3a5ak6v9sb99l.cloudfront.net/content/advances/1/9/e1500605/F5.large.jpg?download=true

Unlike batteries, capacitors have a huge POWER density, because they can dump the entire energy storage in very little time.

Capacitors have low ENERGY densities, relative to batteries, so although they can dump the energy quickly there’s not much of it stored.

The paper notes breakdown voltages of around 15 volts, with working voltage around 10 volts. A supercapacitor with a 10 volt working voltage would have many applications in electronics.

Batteries don’t need a high surface area. All a greater surface area would do, is allow more chemical reaction, so it could give out more power for a particular time. But the amount of energy storage is limited to how much of the relevant chemicals is in there, and which particular chemicals you use. Some chemistries offer better energy density that others, lithium being the obvious one.

+100 for that insight

A large surface area in a battery means that its internal resistance is lower, so it can handle higher currents with minimal internal I^2*R losses. It also let you charge the battery faster without destroying the battery, so while it is not increasing battery capacity, it helps the performance and efficiency

.

FYI: High internal resistance is one of the symptoms when a battery becomes unusable. So may be the increase surface area could prolong the usable life?

Large surface area also makes the battery capable of exploding like a bomb when shorted out internally (crushed, punctured), because of the fast release of energy.

There are no guarantees that the battery with small surface area won’t explode when crushed/punctured. It is a failure mode due to the chemistry.

Really interesting stuff. I wonder how practical it is for actual manufacture. And yet, 2 Wh/kg, that’s really low for a battery, unfortunately.

Think there may be a typo on the 2wh/kg.

That doesn’t sound like very much power. 2 KwH perhaps?

No typo. 2kWh /Kg would be amazing, A tesla could drive 1500Mi with such capacitors.

I don’t think so. Look at the link to the graphic in one of the comments above.

Even with super-duper nano tubes, the cheap Chinese capacitors will still puff up, leak, and cause your stuff to FAIL!

when the manufacturers build within such tight tolerances you’re right. Problem is they’re looking to save 5 cents per TV set and your power supply suffers because it’s not filtering transients as well as it could. All hail the almighty profit margin!

A lot of time the board designers also put caps at the hot areas on the board. e.g. How many times you see the caps are placed right next to a board mounted heatsink(s) of a power supply that relies on convection (natural) cooling?

BTW my old Japanese TV has a cap right between the fins of a U-shape heatsink. They were using a decent Japanese cap. When it died, I replaced it also with a good quality Japanese cap, but that only lasted a few more years.

Please correct 2WH/kg –> 2Wh/kg, there’s nothing more infuriating that nonsense units (Watt-Henry?).

*than

…and give us edit buttons for mistakes of our own.

Oops.

Wh/Kg (Watt Hours) is a very common measure for battery energy density and sounds about right. Around 1% of Li-Ion batteries.

His complaint is that the unit represented by `H` != the unit represented by `h`.

Interesting concept, but it seems to me like the manufacturing of such capacitors is extremely difficult and would drive the price of the product massively higher than current technology. And besides the manufacturing of the part itself, how reliable are these delicate stuctures if you apply some soldering processes and have mechanical and thermal stress applyed in the finished products?

a capacitor could be used as “wipe read” ram i guess. using the static electricity to make a register.

Capacitors ARE used as RAM! And yes, the voltage fades away quickly, in a fraction of a second usually. That’s why DRAM (dynamic RAM) needs refreshing, constantly topping up the capacitors. They don’t use actual capacitors, so much as the capacitance inherent in a transistor. The alternative is SRAM, static RAM, which uses a flip-flop for each bit, so can store data as long as there’s power, and needs no refresh circuit. The disadvantage is SRAM needs (I think) 6 transistors per bit, where DRAM needs just 1. So SRAM is more expensive, and lower in capacity. SRAM has historically been faster though, the external cache RAM on the first PCs to commonly have it (some of the more expensive 80386 models) was, say, 32K or 64K of SRAM, with the main RAM being a few megabytes of DRAM.

One of the early processors, the Z80, had the advantage of built-in refresh circuitry (and a register, R, to keep track of it), so you didn’t need to bother implementing the circuitry. I think in modern PCs it’s the job of the Northbridge on the motherboard.

Some of th older technology (e.g NMOS era processors) uses dynamic logic. The dead give away is the minimum clock frequency is not 0MHz i.e. clock cannot be stopped.

Yep, our Jeri made a video on the subject, was featured here a couple of years ago. Summary: it’s weird.

Leaky. Are they still leaky? Are they also working on commensurately sized inductors?

“Traditionally, capacitors are like really bad rechargeable batteries.”

And rechargeable batteries are like really bad capacitors.

Try making a lowpass filter using a lithium cell as if it was a capacitor, and you’ll see the point.

They’re not saying that capacitors are worse than batteries, just that they don’t act as batteries well. Similarly, a $5,000 blade server is a bad gaming computer because it doesn’t have a GPU, even if overall it’s a more powerful computer.