Everyone’s talking about the Internet of Things (IoT) these days. If you are a long-time Hackaday reader, I’d imagine you are like me and thinking: “so what?” We’ve been building network-connected embedded systems for years. Back in 2003, I wrote a book called Embedded Internet Design — save your money, it is way out of date now and the hardware it describes is all obsolete. But my point is, the Internet of Things isn’t a child of this decade. Only the name is.

The big news — if you can call it that — is that the network is virtually everywhere. That means you can connect things you never would have before. It also means you get a lot of data you have to find a reason to use. Back in 2003, it wasn’t always easy to get a board on the Internet. The TINI boards I used (later named MxTNI) had an Ethernet port. But your toaster or washing machine probably didn’t have a cable next to it in those days.

Today boards like the Raspberry Pi, the Beagle Bone, and their many imitators make it easy to get a small functioning computer on the network — wired or wireless. And wireless is everywhere. If it isn’t, you can do 3G or 4G. If you are out in the sticks, you can consider satellite. All of these options are cheaper than ever before.

The Problem

There’s still one problem. Sure, the network is everywhere. But that network is decidedly slanted at letting you get to the outside world. Want to read CNN or watch Netflix? Sure. But turning your computer into a server is a little different. Most low-cost network options are asymmetrical. They download faster than they upload. You can’t do much about that except throw more money at your network provider. But also, most inexpensive options expose one IP address to the world and then do Network Address Translation (NAT) to distribute service to local devices like PCs, phones, and tablets. What’s worse is, you share that public address with others, so your IP address is subject to change on a whim.

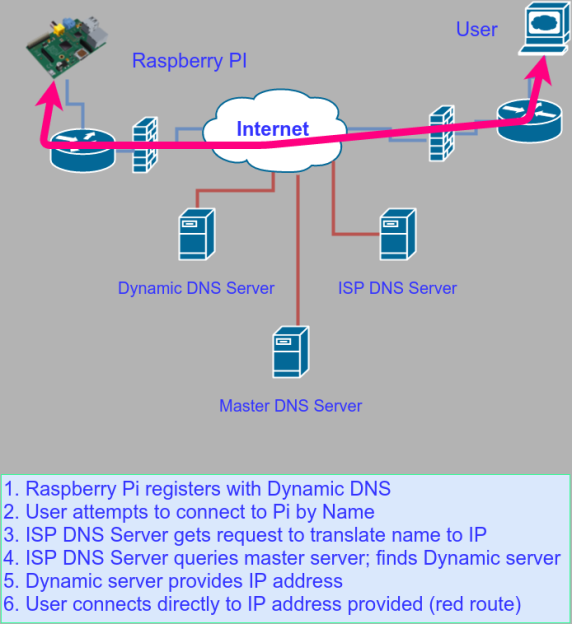

What do you do if you want to put a Raspberry Pi, for example, on a network and expose it? If you control the whole network, it isn’t that hard. You usually use some kind of dynamic DNS service that lets the Pi (or any computer) tell a well-known server its current IP address (see figure below).

That well-known server answers DNS requests (the thing that converts hackaday.com into a real IP address). Now anyone can find your Pi. If you have a firewall in hardware and/or software (and it is a good bet that you do), you’ll also have to open the firewall port and tell the NAT router that you want to service traffic on the given port.

Alien Networks

That’s fine if you are at home and you control all of your network access and hardware. But suppose you don’t know for sure where your system will deploy. For example, perhaps you will use your box at different traffic intersections over a 3G modem. Or maybe you have built a smart picture frame to put in a hospital or nursing home and you want access over the institution’s WiFi.

Granted, you can handle that as a system design problem. For the hypothetical picture frame, maybe it checks a web server on the public Internet periodically for new content. Sure. You can do that. Until you need to ssh into the box to make some updates. Sometimes you just need to get to the box in question.

Solutions

There are a few options for cases like this. NeoRouter has software for many platforms that can create a virtual private network (VPN) that appears to be a new network interface where all the participants are local. If my desktop computer has a NeoRouter IP of 10.0.0.2 and my Pi has 10.0.0.9 then I can simply ssh over to that IP address. It doesn’t matter if the Pi is halfway around the world. The traffic will securely traverse the public Internet as though the two computers were directly connected with no firewalls or anything else between them.

Honestly, that sounds great, but I found it a little difficult to set up. It also isn’t terribly useful by itself. You need to run some kind of server like a Web server. You also need a NeoRouter server on the public Internet with an open port.

A Better Answer

What I wound up using was a service called Pagekite. The software is all open source and there is a reasonable amount of free use on their servers. I would go on to set the whole thing up on my own servers (I’ll talk about that next time). For right now, though, assume you are happy to use their server.

If you go to the Pagekite web site, they have a really simple “flight plan” to get you started:

curl -s https://pagekite.net/pk/ | sudo bash pagekite.py 80 yourname.pagekite.me

That’s it. Honestly, you don’t know these guys so I wouldn’t suggest just piping something off the Internet into my root shell. However, it is safe. To be sure I actually redirected the script from curl into a temporary file, examined it, and then ran it. You may be able to install Pagekite from your repository, but it might be an older version. They also have common packages on GitHub and repos for many package systems (like deb packages and RPM).

That’s it. Honestly, you don’t know these guys so I wouldn’t suggest just piping something off the Internet into my root shell. However, it is safe. To be sure I actually redirected the script from curl into a temporary file, examined it, and then ran it. You may be able to install Pagekite from your repository, but it might be an older version. They also have common packages on GitHub and repos for many package systems (like deb packages and RPM).

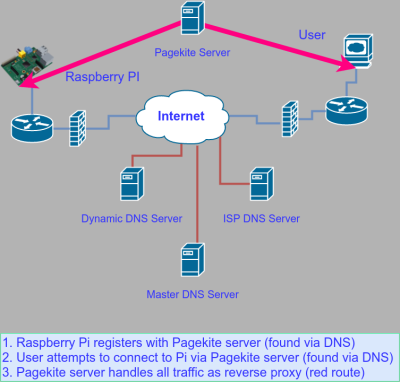

The concept behind PageKite is that of a reverse proxy. Both the remote computer and the user find the PageKite computer via DNS (see figure below). That server acts as a go-between and since nearly all networks will allow access to a web server, there should be no firewall issues.

The last line sets up a redirect from the specified URL to your local machine on port 80. So far that isn’t much different than using NeoRouter. However, the pagekite script is kind of interesting. It can be a backend (that is, your Raspberry Pi serving up web content), or a frontend (like the server at yourname.pagekite.me). It also has a simple web server in it. So if you wanted to serve out pages from, say /home/pi/public_html you could write:

pagekite.py /home/pi/public_html yourname.pagekite.me +Indexes

There is a way to add things like this so they start when pagekite starts (read about the –add option). It all works and it works well.

You can redirect other ports, also. There is even a way to tunnel SSH traffic, although it does require a proxy set up for the SSH client. That will depend on what ssh programs you use. Although it is a bit of trouble, it is also handy since it allows you to SSH into the remote box even on restrictive work or school networks.

Pagekite will give you a chance to sign up the first time you run the script. However, you do need to be on a machine that can open a browser, so if you are using your Pi headless, you might want to set up the account first on another machine.

The free account has some limits, but it does let you set up a CNAME to redirect from your own domain name. You can also create unlimited subdomains (e.g., toaster.myiot.pagekite.me, washer.myiot.pagekite.me, and alarmsystem.myiot.pagekite.me).

On Your Own

If you don’t have a public computer and you don’t have a lot of data transfer needs, the Pagekite free plan might just work for you. I didn’t want to use their domain or be subject to their quotas, so I decided to install the frontend to my own web server. The code is open source, but the documentation for making that work is not great.

Luckily, next time, I’ll take you through the steps I took to get it all working. It isn’t that hard, but it does require a little thought, text editing, and DNS dexterity.

If only there was an encrypted networking tool that could be used from within NAT to expose services on IOT devices that was available on just about every network-capable operating system, and was there by default… like… ssh maybe?

I think the point is how do you SSH into the device when it is behind a network you don’t control? (school, work, mall, etc.)

Reverse ssh tunneling?

Yes, until you need to manage undreds of RPi’s… :( There is only so many ports you can use.

“Only 65535 ports”

Ahah true, but when you need to manage those tunnels by hand, that’s a LOT of ports. There is no software to manage that kind of thing (as far as i know), althouh one can use dynamic “tunnels” using subdomains (like ngrok).

There is a simple and small project named eTunnel to manage ssh tunnels (with the possibility to enable and disabling the single node and its tunnel) on GitHub: https://github.com/gnlcosta/eTunnel

It has also a very simple (too simple) web user interface to manage the nodes and their connections (tunnels).

Woah my google-fu left me down hard… How did i miss that after searching for so long :S Thank you!

I actually have exactly this problem, and approached it by using namedpipes rather than listening sockets.

My SSHD config has the following lines:

# This is to work around a bug only fixed in OpenSSH 7.3 (most likely)

StreamLocalBindUnlink yes

Match User sshvpn

ChrootDirectory /var/sshvpn/

AllowTCPForwarding no

AllowStreamLocalForwarding yes

StreamLocalBindUnlink yes

and my OpenWRT clients run the following SSH command via autossh:

/usr/bin/ssh -o CheckHostIP=yes -o LogLevel=INFO -o ServerAliveCountMax=2 -o ServerAliveInterval=120 -o StrictHostKeyChecking=yes -o TCPKeepAlive=yes -o StreamLocalBindUnlink=yes -o ExitOnForwardFailure=no -o BatchMode=yes -nN -R /sshvpn/gateway-78a3510e3b38:127.0.0.1:22 sshvpn@myserver

Then, on the server I can do things like:

ssh -o “StrictHostKeyChecking=no” -o Proxycommand=’socat UNIX:/var/sshvpn/sshvpn/gateway-78a3510e3b38 -‘ -D 1085 root@gateway-78a3510e3b38

in order to ssh back to the device in question. Then, since I have a -D1085, I can use any SOCKS capable client to connect to anything on that device (using localhost), or reachable from it.

It works pretty well, but I have a couple of enhancements that I’d like to see.

1. The SSH server should delete the named pipe when the client disconnects, rather than me having to get a “Client disconnected” message when I try to connect to the (now disconnected) named pipe.

2. ssh should support binding to a specific interface, rather than just an IP address (i.e. look up the IP address from the interface name). This would allow me to run multiple autossh instances, bound to various interfaces of my router, such that I would always be able to get to the router if any of the interfaces have a route to the internet. This works if I specify the IP address, but that can potentially change if the interface goes down and up again, and I’m trying to simplify the process where possible.

Wait so you can use named pipes instead of using ports directly? :O Does that mean i don´t need to specify a remote port when creating the reverse connection? I need to try this when i get home. Do you have other tutorials or links i can read about this?

Apologies, I only saw your comment now. I think my post contains all you need, it’s working fine in that context for me.

The obvious thing is to avoid collision with the named pipes, but that is easier with a long filename than with a sequence of ports. The trick with connecting via the Named Pipe is to use the ProxyCommand option to establish the connection to the pipe, and then hand the protocol handling over to ssh. You can even establish multiple concurrent connections, in my experience.

As Stranger mentions, you tell the device to SSH out, and forward a port (or many ports, or a SOCKS proxy) over the tunnel from the remote server to the local one. Rogan shows a pretty sophisticated approach to this lower in the thread for managing multiple devices, but for a single device it’s the fastest way to accomplish this. If the network you’re on is paranoid *enough* of course, they’ll only allow actual HTTP out, even over port 80, but those networks are pretty rare.

You could always try ngrok with raw tcp (http://ngrok.com)

Why not use a tor .onion hidden service to punch NAT.

This guy, right here. I’ve done this for a few computers of my own. As long as you don’t need much bandwidth, and don’t mind 500ms latency, this is a very easy, effective way of making an unlimited number of private services and devices accessible from the internet.

This is how I do it. My Raspberry Pi connects to the Tor network and listens for incoming HTTP and SSH connections on a Tor hidden service address. It bypasses NAT and any other firewall. Also has the benefit of hiding my IP address when I connect to it.

What do you think this is, some sort of website for hackers?

This post brought to you by PageKite, our definitely trustworthy corporate sponsor who you should totally expose your devices and networks to because of reasons.

There is also tinc https://www.tinc-vpn.org/

Yet another option is one of a few flavours of IPv6. Depending on where you live you may get it from your ISP out of the box or with very little tweaking. In such case simply configure your firewalls properly and attach your Thing to the Internet.

Even bigger chances are you don’t get IPv6 directly. Then you are going to need to set up a tunnel of sort. There are many tunnel brokers, some of them provide service for free (SixXS, Hurrican Electric). SixXS’ aiccu software is available for OpenWRT there should also be no problem at all running it directly on a Pi. In case you’ve got a static IPv4 addresses assigned to your routers and want to connect Things behind them try setting up 6to4 automatic tunnels.

You might also want to add some security with IPSec too. In either case remember to configure your firewall properly because there is no NAT in IPv6 (NAT is not for security anyway).

Came here to say IPv6. Personally, I run OpenVPN with IPv6 in the tunnel to get information out of closed networks. This gives me a publicly routable IPv6 address from anything that has IPv4/v6 connectivity, whether it’s behind NAT or whatever. Since all of the IPv6 traffic to the embedded device runs through my VPN endpoint, I can control access with the firewall on the VPN server (OpenBSD’s `pf` in this case), so that’s another layer of security on whatever may or may not be in place on the embedded device.

An IPv6 /48 subnet is 100% free from Hurricane Electric, I’m sure other tunnel providers have similar arrangements. I’ve split off a single /64 subnet for my tunnel networks, which really should be enough :)

http://www.resin.io is perfect for this kind of thing and free for up to 5 devices

I use ngrok (https://ngrok.com) on my Pi. It’s a single file which sets up a tunnel and returns a random address which you can then expose things like SSH or webserver.

It’s open source so if you’re scared about sending them your data, you can via the code to see it’s secure (https://github.com/inconshreveable/ngrok)

It’s free to use for a couple of tunnels but then you can pay to get more, custom domain name, or run your own ngrok server on your infrastructure.

I am really blown away by it and think it’s an amazing tool.

ngrok looks great. Thanks!!!

Expose my raspberry? You must be joking, Sir. Imagine the scandal, the shame, the sex offender register!

If you need a computer with a direct internet connection you can always run a VM under AWS

I have used weaved http://www.weaved.com with some success, think it’s $2/month for 100 devices, limited to ~2 hours continuous connection. I think they have a free for less devices/time, and more for more. lets you use just about any port via proxy..

Good writeup for a modern problem. I run an OpenVPN server on my home PC, which my mobile 4G-connected RPi dials back into. Then they can talk as if they’re on a LAN. I freaked out as my whole TKIRV project depended on it but I was glad once it was all humming smoothly. The one thing that still stumps me is that gstreamer doesn’t run over the VPN but I have a solution for that, anyway.

You can use Docker to run one VPN server in the cloud yourself, for free. That should be enough to get all of your IOT things and servers talking to each other wherever they are.

https://hub.docker.com/r/mobtitude/vpn-pptp/

https://cloud.docker.com/

Satellite Internet is only an option any more if you don’t move far. The vendors have been phasing out the old wide-converage sets and going to spot-beam. Five years ago it was hard to find a used set and a vendor that would activate it, I don’t know of anyone still using it. (Cell coverage has been getting better, but there are places it is spotty.)

Just to let everyone know, Neorouter keeps/sends your domain passwords in plaintext.

curl | sudo bash? Really?

When you see that you should run the other way, because you know they have zero clue about security. Zero.

Exactly

For those who don’t like managing ssh there is always https://github.com/apenwarr/sshuttle

Check out zerotier. https://www.zerotier.com

“Honestly, you don’t know these guys so I wouldn’t suggest just piping something off the Internet into my root shell. However, it is safe.”

No you shouldnt. So why are you? Its bad practise.

Do not ever run unknown shit like this as super user.

How is this any different than downloading compiled code from the internet and running it? At least this way you can pipe it to file and see what it does before running it.

If you ignore your systems security and treat it like a windows computer you have gravely missunderstood linux philosophy and security. If you dont know the difference between running a program as super user or as regular user, you probably shouldnt use linux at all.

This is a great article. I’ve search for these types of services in the past and didn’t find them. Definitely looking forward to the article detailing the setup of the front end!

I always struggled with this, my ISP doesn’t provide a public IP (dynamic or static). I found a project called cjdns, and the related network hyperboria. You can join hyperboria or if you can get at least one system on a public IP you can peer all your devices to the same public node and form a network. It’s also able to auto-peer with systems on the same LAN.

You can run it on an RPI, (the crypto is a bit heavy) but it works.

As a paranoid myself, a couple of notes, while it seems having devices exposed is something most advanced users *have* do, I do it myself, please note, while exposing devices, don’t forget the need for security. Limit what you leave open, monitor what you do and remove and default configurations (particularly userid’s and passwords). For those of us who have been around long enough, most of us recognize IoT to be a much more dangerous game, exposing even small unsophisticated devices can be bad news for everyone, even though it might not seem that way. (ie. a legion of ESP8266 IoT devices is still just as bad as a few desktops over broadband; if not worse).

For Unix based devices, where you are exposing SSH (22), if you can, limit access by firewall, or at the least, use “fail2ban” to prevent brute forcers from banging on your boxes for months on end without you knowing about it. If you expose more then one (and you are intrepid enough), consider deploying OSSEC (kind of like Fail2Ban on steriods).

There are, of course, tons of other open source solutions that work similarly, so you don’t have to limit yourself to what I mention here.

If you do consider opening SSH, SSH has some powerful features, consider using keys, consider outright disabling “ChallengeResponseAuthentication” and the use of passwords and just stick to the keys (effectively giving brute-forcers the middle-finger).

Stay safe everyone.

Tuntox solves this problem in a p2p fashion – generates a 76-character ID which you then use on the other machine. The ID is used in DHT to find the node and then as a public key in crypto. Firewall on both sides? No problem, traffic will be relayed p2p via the Tox network. https://github.com/gjedeer/tuntox

You can use RealVNCServer or TeamView to connect Raspberry Pi over the internet .Please refer my web https://bkjaya.wordpress.com/