The types of steps and missteps the Wright brothers took in developing the first practical airplane should be familiar to hackers. They started with a simple kite design and painstakingly added only a few features at a time, testing each, and discarding some. The airfoil data they had was wrong and they had to make their own wind tunnel to produce their own data. Unable to find motor manufacturers willing to do a one-off to their specifications, they had to make their own.

Sound familiar? Here’s a trip through the Wright brothers development of the first practical airplane.

Starting Out: Kites And Gliders

To give you an idea of their background, neither Orville nor Wilbur Wright had aeronautical training. Wilbur completed high school whereas Orville dropped out to pursue the printing business with Wilbur. For that, they’d designed and built their own printing press. In 1890, when the introduction of the safety bicycle caused a boom in the bicycle market, they switched to repairing and selling bicycles and by 1896 where making their own brand.

Many other experimenters around the world were pursuing heavier-than-air flight but with different approaches. Some treated flying as much like a boat on the water, using a vertical rudder for steering. Others felt that humans couldn’t react fast enough to gusts of wind and tried instead make the craft inherently stable, for example, using dihedral wings. The Wright brothers disagreed with this and wanted to give the pilot full control.

They observed that birds turned by changing the angles of the ends of their wings, causing their bodies to roll and change direction. They also felt this would help recover from tilting sideways due to side winds. One day Wilbur was idly twisting a long inner tube box in their bicycle shop when they realized they could twist the ends of their wings in a similar fashion, what they called “wing warping”.

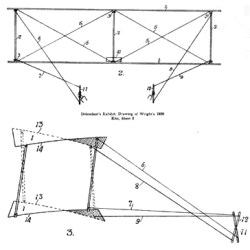

They proceeded with development in 1899 by building a bi-plane kite, or “double decker” as the Wrights called it, with a five-foot wingspan. It was tethered with lines from each wingtip going to control sticks. Rotating the control sticks in opposite directions would suitably warp the wings, making one side of the kite dip while the other rose, resulting in roll and a turn.

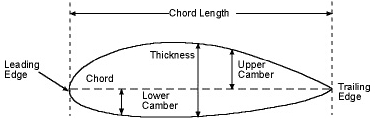

While some inventors at the time considered flat planes for wings, they decided to go with a camber for theirs, a wing with a curved upper surface, a concept that had first been talked about in scientific terms 100 years earlier by Sir George Cayley.

The brothers then looked for a location with a fast, steady wind for their next series of tests and settled on Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, far from their home in Dayton, Ohio. For free gliding, they also made use of Kill Devil Hills, a set of sand dunes up to 100 feet high just 4 miles to the south of the town of Kitty Hawk.

Their glider had a horizontal elevator in front of the wings, a feature also known as a canard and something that was fairly unique to the Wright brothers’ planes. Their main purpose behind the horizontal elevator was to help keep the glider’s center of pressure at the same location as its center of gravity. Without that a plane couldn’t maintain horizontal flight. The elevator could also be tilted back and forth for angling the glider upward or downward to control ascent and descent. Tests in 1900 showed that the elevator worked well.

However, they got less lift from the wings than they expected. They returned in 1901 with a glider that had a larger wing area in hopes of getting more lift. However, they still got less lift than expected, even after making modifications to the curvature of the wings.

Fixing Lift — DIY Wind Tunnel

Initially they had designed the wings with the aid of data from Otto Lilienthal, another experimenter who’d done a lot with gliders, as well as a lift equation that had been in use for over a hundred years. The Wrights suspected both sources. The lift equation was:

lift = kSV2CL

where k is the coefficient of air pressure, also known as the Smeaton coefficient, S is the total area of the lifting surface, V is the relative wind velocity, and CL is the coefficient of lift.

Over the years there were a large number of possible values for the Smeaton coefficient, 0.0054 being the most popular. Using data from their flights with kites and the glider, the Wrights calculated a value of 0.0033 instead, close to a value which Langley, another aviation pioneer was using.

After returning to Dayton, to test the accuracy of Lilienthal’s data, they mounted a bicycle wheel horizontally to the front of a bicycle. Attached to the wheel was a model wing mounted vertically on an axis whose angle relative to the oncoming airflow could be adjusted. Ninety degrees to that was a flat plate with its face facing the oncoming airflow, there to create drag. They rode this bicycle at a constant velocity when the surrounding air was near-calm. The goal was to find an angle for the wing that would exactly counteract the drag of the plate, at which time the wheel would not rotate. Lilienthal’s data indicated that the angle should have been 5 degrees but they found it was around 18 degrees.

They then made a wind tunnel consisting of a sixteen inch square box that was six feet long. They made two balances to go inside and to which miniature wings could be mounted. One balance tested lift and the other tested drag. The wind tunnel had a window in the top for looking down at the balances in action and for taking measurements.

From the wind tunnel tests they came up with a new Smeaton coefficient. They also concluded that Lilienthal’s data was fine, but applied only to the wing shape and curvature that he’d tested with.

In 1902 they returned to Kitty Hawk with new wings. These wings had a longer wingspan and were narrower. They were also flatter, having less of a camber. All this was based on the best of their wind tunnel test results. They’d also replaced the bulky, rectangular elevator with a smaller ellipsoidal one.

All their painstaking wind tunnel tests paid off and in the first day’s testing they flew it successfully as a kite with the tethers almost vertical. That was followed later that day by twenty-five equally successful glides.

Controlled Flight At Last

Another problem they ran into in 1901 was that the glider would sometimes turn in the opposite direction expected during the wing warping tests. This later became known as adverse yaw. To counter that their 1902 glider had two fixed, vertical tails, each six feet tall.

They did still have problems though, the last big one was what they called “well-digging”. If the wings were low on one side (the right wings for example) and the pilot was slow to correct it, gravity would take over and the glider would begin sliding to the right. This then added air pressure on the right side of the fixed tail, which would cause the tail to move to the left and the right wingtip to move through the sand with a screwing motion, hence “well-digging”. The solution they came up with was to replace the fixed tails with a single, hinged vertical tail that was tied to the wing warping system that would swivel in a way that aided the wing warping in lifting the wing.

With the well-digging gone, they felt they had what they needed in order to patent a three-dimensional system of airplane control. They were also ready to move on to the next step, powered flight.

Powered Flight

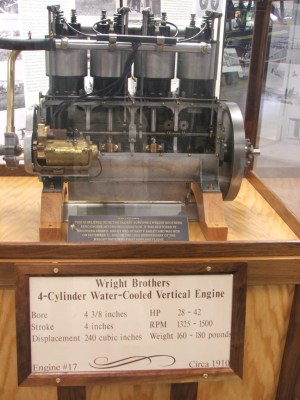

The Wrights were unable to convince a motor manufacturer to make a motor to their specifications so they had to make their own. Together with Charles Taylor, a mechanic and machinist who worked for the Wrights in their bicycle shop, they designed and built their motor using an aluminum crankcase cast in a local foundry, and a crankshaft made of high-carbon tool steel. It had four cylinders and the fuel was gravity fed.

For the propellers their research didn’t turn up any formulas and so they had to theorize on their own. They decided that propellers were essentially wings that rotated in the vertical dimension, and so were able to use their wind tunnel data to design them. They made them a little over eight feet long out of three glued laminations of spruce. They concluded that the propellers were 66% efficient but modern tests indicate they were an even more impressive 75%.

The propellers were mounted behind the wing as pushers so as to not interfere with the airflow around the wings. Chains connected them to the motor. They knew that bicycle chains wouldn’t be strong enough to turn the propellers so they used chains manufactured for automobile transmissions. To keep the chains from flapping they ran them through metal tubes. And to make them counterrotate, one of the chains was made to traverse a figure eight path.

In addition to adding power, numerous other tweaks were made resulting in the Wright Flyer I.

Test Flights

In 1903 they successfully tested the Wright Flyer I near Kitty Hawk, but after its fourth flight it was severely damaged when a powerful gust flipped it over multiple times, ending that year’s tests. This is the one that now hangs in the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

In 1904 they built the Wright Flyer II but from then on did testing at Huffman Prairie, a cow pasture near Dayton. Perhaps the highlight of this was the first flight ever of a complete circle by a manned heavier-than-air powered flying machine. 1905 brought the Wright Flyer III with more improvements, including enlarging the elevator and tail and moving them further from the wings. They also disconnected the tail from the wing warping system and gave independent control of it to the pilot, in keeping with their approach of giving the pilot full control of all three axes. Stability and control were greatly improved, culminating in a 24.5 mile flight in 38 minutes and 3 seconds, landing when the fuel ran out.

They were ready to bring it to market.

But if you think that flight’s pioneering period just after 1900 was the only time home-grown inventors could expand flight’s horizons you’d be wrong. The story of [Paul MacCready], his son and the many others who worked on the Gossamer Condor and human powered flight to win the Kremer Prize in 1977 has all the hallmarks for the Wright Brother’s story you’ve just read. More recently a group that call themselves Aerovelo along with help from various other organizations, won the Sikorsky Prize for a human powered helicopter, Atlas, in 2013. Clearly there’s still room for pioneering.

“They were ready to bring it to market.”

I was always curious, for all of the pioneering work they did, just how lucrative was it for them?

Depends on who you ask & how you measure.

They sold their patents for $100k in 1909 dollars. They did alright but most people think they could have done better.

So ~$2,500,000 in current US dollars? Minus the cost to file all the patents and the time, costs and risk they endured?

Powered flight was a technology waiting to happen, and there were many working in the field. They were probably wise selling out when they did rather than waiting and trying to defend those patents against derivative works.

Oh, they spent considerable effort & money defending these patents. There’s actually an event referred to as the ‘Wright Brothers Patent War’ where they hounded everyone using any semblance of powered flight. They got a bit self righteous in the end.

I always got the impression that they were really trying to do it right…they spent years trying to sell it to various governments, but it was a very hard thing to monetize and keep all the innovation under wraps. I think Curtiss pretty much copied them while making a few improvements after the Wrights had finished development. He got sued for it, but the cat was out of the bag. They did OK. Maybe they deserved better. I think they are deserving of the recognition they get. I guess that is all you can ask for in the long run.

From Wikipedia:

“Orville was badly injured, suffering a broken left leg and four broken ribs. Twelve years later, after he suffered increasingly severe pains, X-rays revealed the accident had also caused three hip bone fractures and a dislocated hip.”

Also more information on their patent struggles:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wright_brothers_patent_war

don’t exist proofs between 1903 1905. The brothers realizations ONLY 1908. Santos Dumont 1906 the real First plane.

Unless they spent the time they where investing the time they spent on the aircraft research on something that would have given a better return, the time invested isn’t relative. The Wrights certainly where not dummies. Perhaps it’s reasonable to assume that their business provide enough income to live comfortably , and spend money to pursue a passion of theirs.

They originally offered the whole thing to the War department for free, but were told the War department didn’t fund crackpots. It took a while for Selfridge to turn that around and the War Department screwed them all over leading to a test that ended with Selfridge’s death. Which stings less because Selfridge was also in bed with Bell and Langley who were trying to screw the Wrights out of their patent claims. Langley was the head of the Smithsonian at the time and had used Smithsonian dollars to fund his pet airplane project.

Langley’s work crashed, failed – he was more tinker class than the Wright’s. When you carefully examine the Wright’s work, one really sees their engineering mind(s) at work. Simple, yet cutting to the core of the problem with what was available; inventing it after careful study when it wasn’t available.

No, they sold for $100K and a third of the stock of the Wright Company, which had a capitalization of $1M at the time. So significantly more than just $100K.

Then there was suing the Smithsonian over their claims that Langley had built the first heavier than air machine capable of flight. Langley had been the Secretary of the Smithsonian at the time and his Aerodrome had been funded by the institution.

Glenn Curtiss was eager to invalidate the Wright’s patents so he wouldn’t have to pay royalties. So he rebuilt the wrecked Aerodrome to “prove” it could have flown before the Wrights. After making a large number of alterations, Curtiss was able to get the Aerodrome up in the air for a short hop.

In the end, the changes Curtiss had to make to enable Langely’s folly to barely get off the ground without collapsing in a heap made it ineligible to be called the first aeroplane (nevermind that in the two attempts Langley made it never did anything except sort of crumple onto the Potomac). The Wright’s patents were upheld and they got paid licensing fees, but they didn’t make much coin manufacturing aircraft.

The Smithsonian also had to remove their display of the rebuilt Aerodrome as the “first airplane” and replace it with the 1903 Wright Flyer. But that plane was not exactly original. Orville rebuilt the plane that had been wadded up by the wind gust, and used parts from some later models. It just had to look right, it didn’t have to be flyable since it was going to be hung on wires. I wonder if they’ve carefully restored it to be exactly like it was in 1903?

There was also Gustave Whitehead who challenged the Wright’s claims…

Don’t forget Glenn Curtiss was also a New Yorker…..

Didn’t Tesla make the first working airplane 15 years earlier? It was powered remotely and used corona discharge needle motors along the wing trailing edges. It wash suppressed by the stage coach industry giants.

Do you have a reference? How could industry giants suppress this effort except by refusing to invest in it?

Great post ! Gotta love the Wright’s for all the hacks they did along the way. And for those interested in a more detailed look into their lives, “The Wright Brothers” by David McCullough makes for superb reading — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Wright_Brothers_(book)

Thanks! I’ll add to that “Wilbur and Orville: A Biography of the Wright Brothers” by Fred Howard — http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/1955303.Wilbur_and_Orville It was one of the main sources for this article.

One more: https://www.amazon.com/Bishops-Boys-Wilbur-Orville-Wright/dp/039330695X

Wilbur and Orville were engineers. They understood trial and error, they kept meticulous records and they had a successful business building and selling bicycles. They kept abreast of what their competition was doing, AND…they were persistent.,

Most of this article seems to be taken from Lester W. Garber’s book “The Wright Brothers and the Birth of Aviation” which was written by an engineer and is specifically about the engineering aspects behind the invention of flight, albeit it in mostly layman’s term. Fascinating book, you see time and time again how their background in bicycle mechanics gave them a distinct advantage over others working on the problem e.g. they realized early on that planes were in many ways like bicycles in that they were inherently unstable without constant pilot input. They also were the first to realize why Otto Lilienthal’s data was so wrong: his lift experiments had been conducted using two wings mounted on opposite sides of a stationary rotating wheel. As bicycle mechanics (and presumably, riders) they correctly recognized that slip-streaming had occurred as each wing passed through the wake of the other; he wasn’t around to ask anymore as he’d killed himself flying gliders based on his own data!

I haven’t read that book but from an engineering standpoint it looks like a good one. Hmmm… can I wait til Christmas?

They worked well together as a team, encouraging one another when they faced a failure along the way. They did not drink, or chase women. All this helped them to pull it off.

Remember: if the women don’t find you handsome, they should at least find you handy.

(just think how much faster they would have flown, if they had been able to use duct tape — the handyman’s secret weapon!)

So you’re saying the Wright Brothers were ancestors of Red Green?

but if they’d have had a K-car to pull parts off, maybe they’d have done it sooner…

Wright-Brothers Succeeded – Why? : NO frivolous Patent encumbrance, NO Trial and Patent Lawyers, NO FAA, NO corrupt/incompetent USPTO, NO NLRB, NO OSHA – Simply put, NO BLOATED GOVERNMENT to STOP them! If you don’t believe me, study what YOU will face to bring something to market, especially in the totally corrupt process of getting anything approved in the medical field today.

Ah. Flying on pills.

This must be why Somalia is such a hotbed of innovation and entrepreneurship.

Well you can’t fault them for enthusiasm…

http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20130625-africas-diy-aircraft-builders

Are you really saying that Somalia today and the 1900s US are in a similar situation?

I doubt my great grandparents would have agreed.

It is time for your dried frog pills again.

Maybe the Arch Chancellor can give him one of his famous pep talks.

Came here for tech, found Discworld references. I am not disappointed in the slightest.

The Wright Brothers succeeded in conspiring with the US War Department to run to the patent office ASAP with an invention that did not work. The Wrights did not fly at Kitty Hawk – the Flyer did not have enough power and was merely picked up by a wind gust, gliding with the engine on. A NASA replica proved this at the centennial, even with modern tweaking of the engine for maximum horsepower.

The reason why they got credit,like many other “inventors” in the early 1900s, was through their actions in court, namely against Glenn Curtiss. They won a controlled flight lawsuit against his ailerons – show me one airliner with wing warping….

You really believe that load of bovine excrement?

There are photographs and witnesses, my good man.

Reference, please, on the “NASA proof” that the 1903 Wright Flyer didn’t fly at Kitty Hawk.

The photographs and evidence don’t show much. Even the New York Times at the time questioned whether they actually did fly, because they didn’t invite any reporters along.

The Wright Brothers were excellent glider flyers and they knew how to use thermals and winds to get a completely non-powered plane in the air. A wind gust can pick you up and then you slide down, appearing to move forward under your own power.

Their first flyer experiments simply didn’t have enough engine power to stay in the air, so they used catapults and the early morning thermals after sunrise to give them lift – the engine being there only for the ride until they refined and improved the power – but that was years after other inventors did their genuine first hops.

Is this part of the new post factual world?

No, the same controversy has been on for over 100 years now.

Problem being that the Wrights dismantled their third flyer to “protect it from spies”, which meant nobody could verify their claims of flight. The earlier flyers had been short hops into the wind no longer than a quarter mile, which is perfectly possible with an un-powered or partially powered glider.

It wasn’t until 1908 that they managed to publicly demonstrate their plane actually taking off and sustaining flight under its own power with a new 35 HP engine, instead of being slid downhill into the wind, or hitched into air by a rope-and-pulley catapult. Before that, it was just “eyewitness accounts” and a bunch of heavy handed marketing.

If you don’t have a particular reason to claim that the Wrights Brothers flew first, all the indications are that they didn’t have a working airplane but they gambled they would at some point, after some improvements, and they were simply trying to beat everyone to the patent office by claiming it worked.

There’s one problem with your final argument: their main patent wasn’t for an airplane. It was for the control system demonstrated in the *glider*, not the airplane.

Claiming *powered* flight didn’t do anything for the patent. It convinced investors and others that the control methods would work for powered flight as well. All they needed to demonstrate in the flight was that they could control orientation and stability.

This is fairly obvious, after all – there’s no engine detailed at all in the 1903 patent.

Claiming powered flight was what the War Department wanted (there was extensive ongoing correspondence, even guidance, from the War Dept with the Wrights). The French actually flew level, controlled, powered first. The Wrights were an excuse to claim prior art and keep France from manufacturing a reconnaissance platform.

>”It was for the control system demonstrated in the *glider*, not the airplane.”

At the time of the claimed first flight, the US Patent office became so filled with applications from all sorts of crackpots on flying machines that they started demanding a working demonstration. An engine powerful enough for flight was exactly what the Wrights didn’t have, so they couldn’t include it in the patent – instead they had to demonstrate the control systems with a towed kite.

The problem was the Wrights didn’t strictly invent any of the methods or mechanisms, some of which even had prior patents elsewhere, in exactly the same way as how Edison didn’t actually invent the lightbulb although he did a great deal of work to better implement it – they simply took the credit and then started suing everybody for trying to make the same.

Ailerons weren’t Curtiss’s invention, and the Wrights directly described using ailerons (“it is only necessary to move the lateral marginal portions”) in the patent. The Wrights got credit and won the lawsuit because they were able to describe what was needed for controlled flight (powered or otherwise!) and demonstrate it. The patent wasn’t even for a powered aircraft.

I remember seeing a movie while in grade school, IIRC Alexander Graham Bell claimed credit for elevators/ailerons…

The US Army and War Dept. were not interested in funding the Wrights. They had been burned by Langley’s failure and were not going to fund a similar project. Eventually, they agreed to fund a flying machine that met a list of performance specs such as the demonstrated ability to fly 40 mi. at 40 mph. This led to demonstration flights in 1908 in Ft. Meyers, Virginia.

The Wright’s US Patent included ailerons. The proof of concept was an aircraft with wing warping. It is the same principle.

Show me one airliner with ailerons that matched those developed before 1910.

For an example of a Wright Flyer with modern tweaking but the same horsepower (under 30 hp) check out the 1905 replica which flew over 800 ft. on its maiden flight. Later flights were over 4 miles long and included banked turns. The 1903 Wright Flyer was unstable and required a wind of over 15 mph to get into the air. The same exact replica flew over 100 ft. in November and early December when there was a 15 mph wind. Wilbur’s 850 ft. flight had a 27 mph headwind.

It may take 100 glider flights with the same controls before a pilot can handle this unstable craft.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ckg_oMeS00U Video of the 1st flight of the USU 1905 replica March 14, 2003

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XPbTM5lKN54 4 mi. flight with turns.

Santos Dumont invented the airplane.

And Clement Ader flew *something* like a plane well before the Wrights:

http://nation.time.com/2013/11/23/the-unlikely-fight-over-first-in-flight/

Is that the bicycle thing with the flapping wings that ends up collapsing?

Rather some kind of steam powered bat-plane.

http://www.flyingmachines.org/ader2.jpg

He coined the term “avion” used in french, spanish for airplane.

At least thirty names should be credited with “inventing” the airplane. By late 19th century it was obvious that an heavier than air craft was possible, many tried, many found small ideas that together made it possible.

There was also the importance of balloons and steerable lighter than air, some had both wings and hydrogen balloons. Like vacuum tubes had an important role in inventing electronics, dirigibles were crucial for early aeronautics, particularly in Europe.

And Santos Dumond built many dirigibles before making the 14bits or the Demoiselle.

Don’t forget Tesla’s plane that beat them all by years.

Interesting!

But only Americans recognize that the Wright brothers as the inventors of the airplane …

The rest of the world knows that it was Santos Dumont who did this first …

Wikipedia says 1906 for his first heavier than air craft. Even if you dispute their article, it would seem that you’re not including the many people who could edit Wikipedia in “the rest of the world”.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wright_brothers#Smithsonian_feud

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/98/Th_Smithsonian_contract.jpg

I’m not sure what that has to do with anything? I’m referencing the Santos Dumont article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alberto_Santos-Dumont#Heavier_than_air_aircraft

Unless you’re saying the Smithsonian has somehow conspired with all possible editors of Wikipedia?

Wright brothers And your motorized gliders. Plane is Other machine

The earliest actual demonstration of the Wrights Flyer taking off and sustaining flight under its own power happened in 1908 after the brothers installed a new more powerful engine to it. Before that there’s no verifiable records or evidence because they always launched their gliders with a catapult or pushed them downhill into the wind.

Yes

There are two books covering these topics that are massively appropriate to this audience:

Dr. Peter Jakab’s “The Wright Brothers and the Invention of The Aerial Age”

https://www.amazon.com/Wright-Brothers-Invention-Aerial-Age/dp/0792269853

Dr. John D. Anderson’s “A History of Aerodynamics And Its Impact on Flying Machines”

http://www.cambridge.org/us/academic/subjects/engineering/aerospace-engineering/history-aerodynamics-and-its-impact-flying-machines?format=PB&isbn=9780521669559

The wind tunnel story is worthy of a Hackaday entry by itself. For starters, the way that they balanced the lift of one test wing against the drag of a known plate, thereby cancelling out all the terms in the lift and drag equations (and eliminating any variability due to temperature, barometric pressure, or humidity) and saving tons of computation in a world without computers was elegantly brilliant. The balances themselves, manufactured from shop scrips – spokes, nipples, and hacksaw blades. The tunnel was itself was an engineering marvel, powered (as was all the machinery in the bicycle shop) by a gas engine of their own design and manufacture that was fueled by the Dayton town gas light supply.

“From the wind tunnel tests they came up with a new Smeaton coefficient. They also concluded that Lilienthal’s data was fine, but applied only to the wing shape and curvature that he’d tested with.” — this sentence is not quite factual. Smeaton’s coefficient is completely unrelated to wing shape or curvature; it is related to the density of the air through wich the wing is moving. The wing shape and curvature are captured in the coefficient-of-lift term in the lift equation.

https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/Wright/airplane/smeaton.html

https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/Wright/airplane/lifteq.html

OOOPS, No!

This is the Peter L. Jakab book you REALLY want:

Visions of a Flying Machine: The Wright Brothers and the Process of Invention

https://www.amazon.com/Visions-Machine-Smithsonian-Aviation-Spaceflight/dp/1560987480

I have both, but THIS is the one that is extremely germane to these topics.

Great article! Thanks. It has very important lessons for today.

As for Mr. Knowitall, is this like the US moon landings? The Vin Fizz didn’t really fly across the US. It was all a fake in collusion with the news media?

There is no wind on the moon to create a gust to lift the craft so it could glide 108 feet, so the moon landings ate intact. NASA used CFD to tweak the century Flyer and they tried all the tricks in the book on the engine to get the power up – it would not fly. It can’t overcome the drag on 8HP or pump enough air to lift itself.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Traian_Vuia

His actual witnessed flights were 4 and 5 meters, compare with the then current long jump record of 7.61 meters.

Even with their wind tunnel, the Wrights were still working with a mathematical disadvantage due to not knowing that a small scale test airfoil doesn’t scale linearly to full size due to how air behaves. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reynolds_number#Flow_around_airfoils

Naturally, someone has to figure out what such effects are, figure out how to calculate them, then do the calculations on airfoils before a couple of guys working in their shop without such knowledge could look this up in a book to figure out how to adjust their small scale wing shape when making it full size. Kind of difficult to do when there’s been little research into the fluid dynamics of airfoils.

The Wrights did look into data about ship propellers but soon discovered that most of what works with water isn’t applicable to air.

They did have some rather good luck, under-calculating their propeller efficiency led them to over-size them, which compensated for the wings underperforming. They also had plenty of flight time with their control system through the series of gliders, culminating with the final glider that was very close to the design of the powered version. Their designs were on the edge of controlability, without the practice they’d had with the gliders, they wouldn’t have been able to control the 1903 powered plane. More observations and tests got their designs to the point where they had planes stable enough that people not intimately familiar with every part of the plane and how it worked could be taught to fly them, especially after they switched from the prone position using a hip cradle to operate the wing warping, to a seated position using a wheel on a tilting control column for roll and pitch, with foot pedals for yaw.

What you say about how they wouldn’t have been able to control the 1903 power plane without having done the glider work first is what makes me admire about their approach. Rather than throw in all the possible bells and whistles in vogue at the time, and given, as you point out, how little was understood at the time, they worked their way up component by component, testing and understanding each before working on the next.

interesting article – though clearly written by an american given the assumptions.

However, they missed a better story – the Wrights were the early Apple – ie take what other people were doing, improve it a bit, and the legislate the hell out of anyone who disagrees with your ‘brilliance’ or version of history..

The Wrights didn’t take wing warping from anyone. No one was willing to build a suitable motor. No one published extensive aerodynamic data. No one linked that using deflection of the wing to induce roll would also induce adverse yaw.

That mostly leaves that they didn’t invent wood, fabric, wire, or power chain and sprockets.

The patent was for their control system; as mentioned it wasn’t taken from anyone. The only ones trying to rewrite history were Langley and Curtis for ego and cash respectively.

The wing warping idea was an earlier invention.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wright_brothers_patent_war

>”American John J. Montgomery invented and experimented with controllable spring-loaded trailing edge “flaps” on his second glider (1885) for roll control. Roll control was later expanded on his third glider (1886) to rotation of the entire wing as a wingeron.[25] Later, Montgomery independently devised a system for wing warping, using model gliders first and then man-carrying machines with wing warping as early as 1903 through 1905 such as those used on The Santa Clara glider (1905). Montgomery patented this system of wing warping at precisely the same time as the Wrights,[26]”

It wasn’t an entirely novel idea, and other people had surely noticed that rolling causes yaw because they had tried it, but the Wrights patented it – and other methods of control including ailerons – and sued the hell out of everybody trying to build airplanes.

and this is why patents are and have for the most part always been, badly implemented.

ideally one would like to protect ones idea but with so much abuse one cant help but wonder if it has hurt more people than it helped.

I guess earlier = simultaneous or later.

>”I guess earlier = simultaneous or later.”

Montgomery actualy beat the Wrights to the patent office by about 4 months. The actual idea had been around and described before the Wrights were even born.

Even the three axis control of an airplane was patented by Boulton in 1868. The US patent office however didn’t take the British patent into account when handing the Wrights patents for the control systems for all kinds of airplane control mechaisms, including wing-warping and ailerons despite the numerous prior inventors.

Englishman Matthew Piers Watt Boulton patented a system of lateral flight control in 1868. That should have come up when Wright applied for a patent in England. It may not have been renewed.

Reference to patent battles.

https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/abs/10.2514/6.2019-0123

Lateral Control: Wrights vs. Montgomery

Wikipedia has several pages on John J. Montgomery.

Montgomery was a college physics professor at Santa Clara

college in California.

you should read this…

http://www.ctie.monash.edu.au/hargrave/hargrave.html

it looks like everyone and their dogs was working from the same journals.

While the Wright brothers denied that they owed anything to Hargrave, his discovery of the cellular kite and his investigations into the superiority of curved wing surfaces played an important part in European experimental work which culminated in the first public flight by Santos-Dumont in France in 1906. His son and fellow experimenter, Geoffrey Lewis Hargrave, was killed at Gallipoli in May 1915, and this terrible news caused him to become seriously ill, and he died in a hospital on July 6, 1915

I guess if you’re not Australian you might not have heard of Hargrave, he used to be on our $20 notes, along with some box kites, some of which looked like Wright flyers, sans engines.

the Wrights and Dumont both credit Hargrave.

the best quote, from Hargrave

“Workers must root out the idea that by keeping the results of their labors to themselves a fortune will be assured to them. Patent fees are so much wasted money. The flying machine of the future will not be born fully fledged and capable of a flight for 1000 miles or so. Like everything else it must be evolved gradually. The first difficulty is to get a thing that will fly at all. When this is made, a full description should be published as an aid to others. Excellence of design and workmanship will always defy competition.”

Hahaha. What a strange view of early Apple. Improve it a bit. Ha! Like invent the color encoding and display system that interleaves with the DRAM refresh. Invent group code encoding (Check GCR for floppy disks https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Group_code_recording ) for a software controlled disk read/write that uses almost no hardware. [Later, Commodore made one with a more complicated encoding that was a little denser, but it required a couple of 6502s and GPIO chips in each drive.]

Create a complete 80 bit floating point in 256 bytes. Invent a very useful latching “soft switch” by using a common logic chip “backwards”, etc. etc. An overload of extreme cleverness. All on a microprocessor at 1/8 the clock of an Arduino.

The whole thing was published in the “Red Book” in April 1977 – code, schematics, the works. Whom do you think copied who?

Excellent post!

Don’t look up their present day decedents unless you want to be horrified.

Or perhaps they weren’t the first to fly ?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Pearse

“It is claimed Pearse flew and landed a powered heavier-than-air machine on 31 March 1903, nine months before the Wright brothers flew their aircraft.[1] The documentary evidence to support such a claim remains open to interpretation, and Pearse did not develop his aircraft to the same degree as the Wright brothers, who achieved sustained controlled flight.[2] Pearse himself never made such claims, and in an interview he gave to the Timaru Post in 1909 only claimed he did not “attempt anything practical … until 1904″.[3] Pearse himself was not a publicity-seeker and also occasionally made contradictory statements, which for many years led some of the few who knew of his feats to offer 1904 as the date of his first flight.”

George Cayley!

no love for Hargrave????

http://www.ctie.monash.edu.au/hargrave/hargrave.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_Hargrave

a few years ago, for the Kitty Hawk anniversary, a group at Gawler built and flew a Wright Flyer, they managed 4 times the distance.

We’ve all seen pictures of the Flyer, but standing next to one is pretty impressive, it’s a lot bigger than you would expect and nowhere near as flimsy.

Not on the original engine design they didn’t. I seem to recall off the top of my head they were running north of 12HP whereas the Wrights’ engine was 8HP on a good day. As John Roncz said in a talk I attended at Oshkosh – “That thing out there [this was one of the first public unveilings of the F-117 Nighthawk] is proof that with enough thrust, you can make a barn door fly. Here’s 20 bucks to anyone who can take a picture of it with an autofocus camera [they used infrared for camera focusing mechanisms at that time]”

The Wright brothers were to flight what Edison was to electricity. They weren’t first, they weren’t the best, bu tthey used the patent system to keep others from succeeding. And if they were Edison then Gustave Whitehead was Tesla: he did it in 1901, but the Wright brothers smeared him in the media and blackmailed the Smithsonian to keep his story down.

But what about Tesla’s electric plane of 1882?

I’d guess that Octave Chanute (US War Department) was the master puppeteer in all of this, including providing the Wrights with espionage information. http://invention.psychology.msstate.edu/inventors/i/Wrights/library/Chanute_Wright_correspond/1905/Nov16-1905.html

C’Mon Man! Everyone knows that was Santos Dumont who invented the airplane.

No way, man!

Trying to put that in the head of an American is almost impossible … kkk

It was Tesla!

Clearly if you want to invent the airplane you must first invent the universe.

Clearly Santos Dumont was an alien introducing new technologies to humans. He teletransported himself and made the 14-bis and the iWatch (ops) wrist watch. :P

Forgot the mention that Santos Dumont was an alien from Planet Brazil…

forgot the mention that Dumont, the Wrights and Bell ALL referenced Hargraves work…

http://www.ctie.monash.edu.au/hargrave/hargrave.html

I agree with @Regis, one unique name: Santos Dumont !! The brothers just threw off a cliff the “airplan” that not counts!! : )

Pretty radical story. Thanks for sharing!

its all a lie