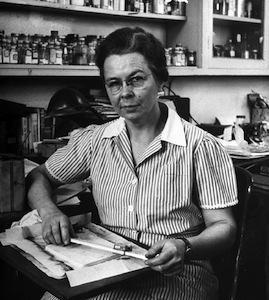

Whether you realize it or not, Katharine Burr Blodgett has made your life better. If you’ve ever looked through a viewfinder, a telescope, or the windshield of a car, you’ve been face to face with her greatest achievement, non-reflective glass.

Katharine was a surface chemist for General Electric and a visionary engineer who discovered a way to make ordinary glass 99% transparent. Her invention enabled the low-cost production of nearly invisible panes and lenses for everything from picture frames and projectors to eyeglasses and spyglasses.

Katharine’s education and ingenuity along with her place in the zeitgeist led her into other fields throughout her career. When World War II erupted, GE shifted their focus to military applications. Katharine rolled up her sleeves and got down in the scientific trenches with the men of the Research Lab. She invented a method for de-icing airplane wings, engineered better gas masks, and created a more economical oil-based smokescreen. She was a versatile, insightful scientist who gave humanity a clearer view of the universe.

Early Life and Education

Katharine Burr Blodgett was born in Schenectady, New York in 1898 to George Blodgett, a patent attorney for GE, and Katharine Burr. Tragedy beset the family a few weeks before Katharine was born when her father was shot and killed by a burglar. The family moved around for a few years after that, spending time in France and Germany so the children could be exposed to more languages. They eventually settled in New York City and Katharine was enrolled at Rayson, a prestigious private boarding school for girls.

When she was fifteen, Katharine won a scholarship to Bryn Mawr for the promise she showed in science and mathematics. She went back to Schenectady on winter break during her senior year at Rayson. While there, she toured GE’s Research Lab with Irving Langmuir, a scientist who had worked with her father. Langmuir was taken with Katherine’s great enthusiasm for science and encouraged her to continue studying math and physics so she could come back and claim a place in the lab.

Katharine graduated with a BA from Bryn Mawr in 1917. She took Langmuir’s advice and kept going, earning a master’s in physics from the University of Chicago just a year later. Anticipating a career of industrial research, Katharine focused her masters’ thesis on the chemical structure of gas masks and determined that charcoal would best absorb a variety of poisons.

From Mere Assistant to Major Asset

That same year, Katharine started working as Langmuir’s assistant. Now she was officially GE’s first female research scientist, and Langmuir set her loose on some of his own early research into perfecting the lifespan of tungsten filaments.

Within a few years, Katharine realized she would need a doctoral degree in order to get anywhere at GE. Langmuir was able to pull some strings, and in 1924, Katharine enrolled at Cambridge University. She studied under renowned physicist Sir Ernest Rutherford of Cavendish Laboratory and, after two years, received the first PhD in physics that the University had ever awarded to a woman.

Meanwhile, back in Schenectady, Langmuir had been studying the chemistry of substance adhesion at the molecular level. He’d discovered that when oily substances such as barium stearate are deposited on a substrate of water, they will spread and form a film on the surface that’s one single molecule thick. He was looking for practical uses for these mono-molecular films and encouraged Katharine to expand on his research when she returned to the States.

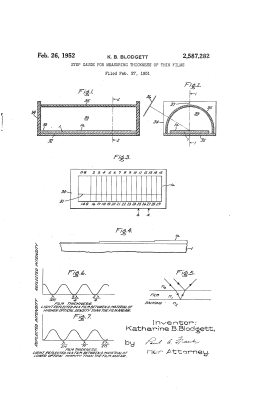

One day, Katharine tried dipping a metal plate into one of Langmuir’s films. The plate attracted some of the molecules and they formed the same type of mono-molecular coating, now known as a Langmuir-Blodgett film, on its surface. She dipped this plate into the filmy water over and over again, and the barium stearate built up on the plate in soapy, single-molecule layers. Their method of depositing single-layer films onto substrates culminated in the Langmuir-Blodgett trough, a lab apparatus the two invented to apply films and measure the resulting phenomena.

Katharine repeated the experiment and found that a different shade of soap bubble formed on the plate’s surface with each new layer of molecules. And these changes were consistent. Without fail, each layer would produce the same color every time. She had stumbled upon a new way of measuring the thickness of mono-molecular films by color-matching them to her established gradient.

As it happened, her method was much cheaper than anything else available at the time, and was far more accurate to boot. Katharine’s tool could measure in microinches, or one millionth of an inch, whereas existing methods measured only in thousandths. In 1952, she received a patent for her marvelous tool hack, the barium stearate stepgauge.

The Future is Crystal Clear

Katharine’s greatest triumph came in 1938 when she discovered a way to make ordinary soda-lime glass 99% transparent. She found that coating it with exactly 44 mono-molecular layers of barium stearate via Langmuir-Blodgett trough creates a film with one-quarter the wavelength of white light. This coating causes the valleys and troughs of the two wavelengths to match up and cancel out, and no light is reflected back from the surface of the glass. More importantly, only 1% of the light coming in is blocked by the coating.

The only trouble with this magic film was its staying power—barium stearate is basically liquid soap, and is easily wiped away. A few days after Katharine’s discovery, a group of MIT researchers announced that they too had created transparent glass using calcium fluoride condensed in a vacuum. While their method wasn’t particularly lasting, either, both solutions provided valuable insights that led to the development of a hard, permanent coating involving a second type of glass containing metal.

An Invisible Legacy

Between 1940 and 1953, Katharine was awarded eight U.S. patents and is listed as sole inventor on six of them. She received numerous accolades including a Francis Garvan medal from the American Chemical Society, and five honorary doctorate degrees.

Katharine retired from GE in 1963. She lived her entire adult life in Schenectady and was a fixture of the community theater in retirement. She remained active in a number of hobbies and even wrote funny poems. She never married or had any children, living primarily with other single women in Boston marriages.

Katharine went quite far in life, further than some people dare to dream of going even today. While it’s true that she received a much better education than most children of the era (especially girls), she was passionate about science and worked hard to get where she did. We as technophiles, scientists, and consumers are mired in Katharine’s invisible legacy that continues to inspire surface chemists today.

So what’s the wavelength of white light then?

That 1/4 wavelength comes from the patent. It is more precisely written to say some component of.

“The layer is then etched or otherwise treated superficially to remove the metallic constituent to a depth which corresponds approximately to a quarter wavelength of some component of visible light.”

It appears 589 nm is the number you are looking for.

“These values are measured at the yellow doublet D-line of sodium, with a wavelength of 589 nanometers, as is conventionally done.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Refractive_index

That’s why real modern broadband antireflection coatings have many layers.

It’s actually multiple wavelengths going into your eye at the same time. Sun light is much more than we see because our eyes only have the capacity to sense three frequency ranges (colors). When our brain gets all three colors at once, it’s what we perceive as being white light.

“Katharine was a surface chemist for General Electric and a visionary engineer who discovered a way to make ordinary glass 99% transparent.”

So who was the one that developed pure transparent aluminum? ;-)

I believe it was a causality paradox that occured when Kirk & crew went back to save the whales.

That’s called sapphire?

Aluminium oxynitride trade name alon used to make windows in armored military vehicles.

Which car windshields have antireflection coatings? None of mine ever did. I’m feeling left out. I have to resort to more plebeian solutions, like using polarized sunglasses and relying on Brewser’s angle. (hey, there’s a HaD article for you…)

More than a few. I think the Ford Tarus was one of the early ones and it’s semi-metallic anti-reflection coating pretty much rendered the EZPasses of the day useless.

Nope. Metalization does not confer antireflection properties. It *enhances* reflection. Specifically for IR and UV light, to reduce heat gain in the cabin.

Yes, my only gripe with this writeup was that portion. Something’s not quite right with the explanation given, since (as Oxfred points out) white light doesn’t have a single wavelength (being the combination of all visible light wavelengths). Otherwise, good piece — thank you for writing it up! I love hearing about these forgotten scientists and engineers.

Simple anti-reflection coatings cancel reflections at one wavelength and reduce them at nearby wavelength. Modern multi-coatings work at multiple wavelengths and do a better job, but the field all started with the single coatings discussed here.

Some of these profiles of engineers and scientists have been most interesting, but why have the recent two dozen profiles been only women? Is this part of a series? Should it be tagged as such?

We did get Isambard Kingdom Brunel recently enough, so I think you missed at least one. Admittedly, the majority of features on specific people in the history category are women, but that can be attributed to a bunch of factors, such as novelty value (a lot of people have heard of folks like Thomas Edison, Tesla, Ford, etc, and fewer features already exist on these women), candidate pools (There may just be a larger pool of clever women with multiple accomplishments, as a single one may be worthwhile to feature the accomplishment and mention the person later, or that the men involved are more anonymous, or else that as many of these are about events proximal to WW2, serving in the military or Manhattan project at the time). Finally we have selection bias, which, as multiple people write these articles, and we had Isambard recently enough, doesn’t seem like a huge issue.

Anti reflection coatings on car windshields? Since when? They reflect so well that at a restaurant I frequent, sunlight bounces off the south facing windows, off the windshields of cars parked facing those windows, and enough light cones through from that secondary reflection to be painfully bright.

I would expect the coating to be on the inside of the windshield, to help the driver. It wouldn’t be very long lasting on the outside anyway.

Why wouldn’t it? According to the article it’s made of glass, after all..

What’s that bit about carbon absorbing poisons? I think that is probably much more influential than anti reflection coatings!

WWI gas masks used “Kleenex” to filter,

activated charcoal (carbon) came later.

Langmuir also worked with Kurt Vonnegut’s scientist big brother, Bernard, and is credited with inventing the idea of Ice-Nine. Cat’s Cradle is a brilliant book.

Vonnegut’s brother was still teaching @ State University in Albany when I was a student there in the 80’s.