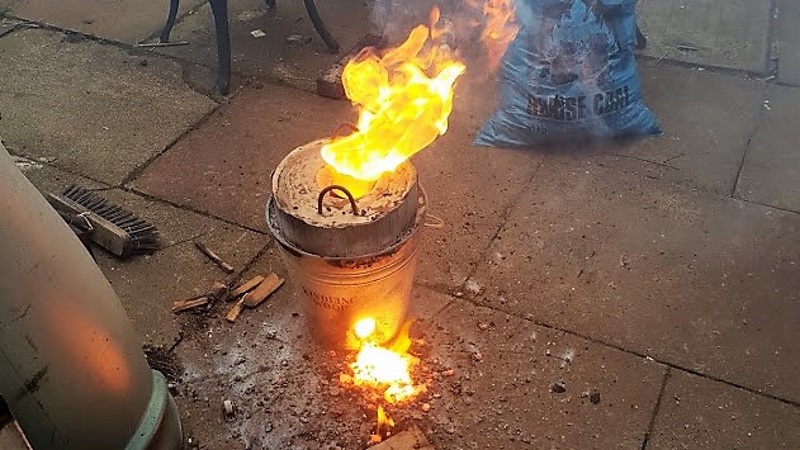

Like many of us, [Tony] was entranced by the idea of casting metal, and set about building the tools he’d need to melt aluminum for lost-PLA casting. Little did he know that he was about to exceed the limits of his system and melt a hole in his patio.

[Tony]’s tale of woe begins innocently enough, and where it usually begins for wannabe metal casters: with [The King of Random]’s homemade foundry-in-a-bucket. It’s just a steel pail with a homebrew refractory lining poured in place, with a hole near the bottom to act as a nozzle for forced air, or tuyère. [Tony]’s build followed the plans pretty faithfully, but lacking the spent fire extinguisher [The King] used for a crucible in the original build, he improvised and used the bottom of an old propane cylinder. A test firing with barbecue charcoal sort of worked, but it was clear that more heat was needed. So [Tony] got hold of some fine Welsh anthracite coal, which is where the fun began. With the extra heat, the foundry became a mini-blast furnace that melted the thin steel crucible, dumping the molten aluminum into the raging coal fire. The video below shows the near catastrophe, and we hope that once [Tony] changed his pants, he hustled off to buy a cheap graphite or ceramic crucible for the next firing.

All kidding aside, this is a vivid reminder of the stakes when something unexpected (or entirely predictable) goes wrong, and the need to be prepared to deal with it. A bucket of dry sand to smother a fire might be a good idea, and protective clothing is a must. And it pays to manage your work area to minimize potential collateral damage, too — we doubt that patio will ever be the same again.

Ugh, don’t call that man just “The King.” He doesn’t deserve it. The King is definitely Elvis.

Well what do you think Elvis has been up to since he was granted immortality under the condition that he fake his death? ;)

Lobbying to make Burgers smaller everywhere world wide, Every year the price of burgers goes up world wide and those burgers get slightly smaller.

Are you sure you’re not just getting bigger?

Yikes! I’m no expert, but that looked to me like there might have been a bit of a thermite type reaction going on there.

That’s actually one of the more entertaining “fails” I’ve seen.

Good job. It’s sort of like the value in publishing null results – you get to see what other people have done that didn’t work out.

quite possibly. I was “interested” to see where his blog was headed once I read he was using paster of paris as the lining for his furnace. Aluminium will burn if combined with paster of paris and ignited (it uses the paster and water contained in it, as an oxidiser).

I think it was just the aluminum getting blasted into a mist by the leaf blower and then burning. He made the mistake (understandable at the time) of pulling the blower out before cutting power which cast sparks every where.

I will suggest, among other things, putting the furnace on bricks, regardless of what surface is below it, and putting some bricks around it so that if/when it does fail, you don’t end up wading in molten metal. Also cutting a big hole in the bottom of the blower line going into it, and then taping over that with something like duct tape, that’ll melt through and fail when you have a crucible failure, so the molten metal doesn’t run back and fill your blower fan and possibly manage to short the windings.

It also helps to put the crucible up on a bit of something (I use a chunk of steel) so heat can get somewhat underneath the crucible, as this seems to even out the heating. I’m using a welded steel crucible for aluminum, because it’s harder to damage than my graphite one, and it’s worked better as I’ve increased the surface area getting heated by doing things like lifting it and encouraging better circulation inside the furnace.

(Also, propane costs more than coal, but it’s sure more convenient as a fuel.)

I like his enthusiasm for attempting this and I commend him making his fail public and allowing us to learn from his mistakes. However, as a molten-metal-making-ignorant person, I could not help cringing while watching the video. My takeaways are:

1. Never walk away and leave the foundry unattended.

2. Place the foundry safely away from and clear of structures and other items.

3. Always keep fire fighting gear within reach such as a fire extinguisher and sand–not for the foundry but for extinguishing other things that could catch fire. I suspect trying to extinguish the foundry would spray/splash burning molten metal everywhere, cause the foundry to shatter, or worse.

4. Wear the proper clothes and safety equipment.

5. Always expect your equipment to fail and things to go wrong, especially when attempting the first time.

Or maybe I’m just too afraid of burning liquid metal.

No, your points are spot on.

The biggest actual danger with casting is getting a drop of water inside something, so when you pour the molten metal the drop turns to steam and explodes, showering the area with molten droplets of metal.

…and I’m getting this direct from a friend who used to do metal casting professionally for many years.

Thick clothing is essential, with full face protection rated for molten metal. I have these and use them when casting. Hard shoes instead of sneakers, and wear gloves.

After that, regular precautions for mildly dangerous actions (ie – don’t set your house on fire) as you pointed out.

As a suggestion, it’s useful to make your kiln from two pieces, a base and column that sits on the base, so if your crucible cracks it’s easier to take apart and repair.

One young guy that I used to work with did put his kitchen pan, who’s oil had cached on fire, under the tap to extinguish it. The whole thing exploded into drops of burning oil and steam right in front of him and severely burned him.

His skin color turned from natural brown to multiples spots of white from the hands up to his head.

I’ve seen the documentary showing what happens when you do that. I made sure that everyone in my household took good note of that. Standing order is to put the lid on a pan and place it on floor tiles, as far from cabinets as possible, open kitchen window and then wait for substantial time until fire hopefully chokes out before attempting to lift the lid.

Baking soda, class B dry chemical fire extinguisher.

Ostracus:

For this kind of oil/fat fire there is a special type of fire extinguisher: class “F” (like “fat”). It’s a special type of foam and quite expensive. I have been told in the fire warden training, that dry chemical (typical ABC powder) is not very helpful against cooking oil fires, probably because there is a danger to spread it with the pressure.

The basic message was: “If you don’t have class F extinguisher put a lid on.” Which is probably the best to do anyway.

Martin: Having witnessed first hand a grease fire (wife & sisters attempting to deep fry wet potatoes over a gas stove…), I can attest that a lid works very well. If you have nerves of steel to put your arms that close to a raging fire.

When the flames burst, I instinctively went for the fire extinguisher (see my comment below – I have also witnessed and practiced using a class B extinguisher on grease fires – works very well, but I appreciate your thoughts on the blast spreading the fire if too close) while my brother-in-law went straight for the pot. He slammed a lid on it, and then carried the still flaming assembly outside with me just feet behind ready to douse any rogue flare ups. The flames were gone by the time we got outside, so my backup services weren’t needed. No damage to the kitchen / house (not even smoke damage).

When all was said and done – the ladies stood in amazement wondering how we knew what to do and how we had reacted so fast.

Nothing special about the gender.

Nothing beats actual hands on training.

Always have a dry-chem fire extinguisher in the kitchen.

Always check / be aware of when it needs to be re-certified.

Teach your kids how to use it. $50 for an extra extinguisher is cheap tuition. Make a little camp fire in the back yard, buy a cheap iron frying pan from a yard sale / thrift store. Put some oil in it, catch it on fire and give your kids the fire extinguisher to put out the fire.

An extinguisher only lasts ~10 seconds. That’s plenty if you know how to fire 1/2 second bursts at the base. It’s not even close to enough if you panic and spray everywhere but the right place.

I was able to have 3-4 kids take 2-3 turns each putting out the grease/oil fire before the extinguisher ran out.

Hope they never need to use that knowledge, but also, if needed, they might be the only people around who will have a fighting chance of instinctively acting properly.

Bravo!

I’ve gotten extinguishers from the fire department before, took two old dead ones in plus one that was still showing charged but was 10+ years old, they took them and gave me two dry chemical and a CO2 for the kitchen. Not sure if every fire department does it or not though, guy I spoke with said they sent them off and they got refurbished or recycled depending on age, and each department got an allotment of extinguishers to give out.

Every single one of your points is noted. I just wish I’d read this article before I started. Oh, hang on…..

Sand is one of the few things to control metal fires. For more reactive types of metal cement (powder) or salt is an option. Of course you should not forcefully throw the sand onto the molten/burning metal, otherwise it could splash.

I don’t see you as “too afraid”,this a re very valid points and I thought alredy a t the beginning “is he doing this indoors” – or just very close (too close) to his house.

Many years ago my Uncle built an all electric furnace. He used coiled nichrome wire from a set of open heaters designed to screw into light sockets. He build the base, back, sides and top out of fire brick then had rows of the coipled nichrome wire run across the back and both sides. He would put pennies in the crucible, put some powder on top he called flux. Then he would place the crucible in the center and stack fire bricks across the front. Then he’d unplug his dryer and plug the power plug into the dryer outlet. He had no problem melting 2 rolls of copper pennies at a time. It seems my uncle’s solution is a lot safer than setting up a blast furnace!!!

There’s pros and cons to having an electric furnace (I have one).

Electric furnaces take a much longer time to heat up and melt things. Much, much longer. OTOH, the electricity is cheap compared to propane, but I’m about ready to go build a propane furnace just to avoid the long wait times.

If you’re using a conductive crucible such as a steel cup or pipe, you have to remember to completely disconnect the furnace before taking it out, because the coils can still be live, even when off, and if you touch them with the tongs or the flask you can get a nasty shock. (Some kilns are mis-wired to switch the neutral off, so when off the coils can still shock you.)

Flux prevents a film of oxidation from forming on the surface. Lots of things can be used as flux – borax is commonly used. It melts and forms a pool on the surface over the molten metal, preventing oxygen from getting to the melt.

Thanks, my uncle was a master machinist and he knew a lot about metals. I was wondering what the flux might have been. I was 14 when he did this 44 years ago. He was making a replacement door handle for an old Studebaker. I don’t remember the whole process, just bits and pieces. He made a mold of the handle from the other side, poured copper into the mold, did some touch up welding then a lot of finishing before sending the part off to the plater.

Flux is often Borax and sometimes fluorine compounds like fluorospar (?) or cryolith. The name of the element even comes from the use of some of its compounds as flux.

Regarding the electrical hazards, a breaker which disconnects all poles would be a good thing.

Is that a CCTV cam in his backyard?

yep.

I think part of the problem was him using coal instead of coke, charcoal, or another fuel all together.

Coal, even ‘clean’ coal has a lot of nasties in it that burn releasing all manner of SOx and NOx that will vitrify your refractory and/or corrode nearby metal, such as a steel crucible containing your melt. Coal also has a tendency to swell as it burns or cokeifies, which can tip your crucible over or damage your equipment.

So many stupid mistakes made here. First, and again, never work hot metal over concrete.

Second, molten aluminum dissolves steel. Thats why you do not use steel for crucibles. Go to a foundry supply place and pick up a crucible, they are consumable items and not very expensive.

There is a thread I started in the video that this guy based his furnace off of saying not to do this and he did it anyway.

This is the one thing i hold against these YouTubers who demonstrate these techniques. It gives people a false sense of security that, “well, HE did it with no problems, so can I, and with 1/100th the research!”

I understand that we all, “own our own safety” but you have to know that if you lay out plans that purposefully sacrifice safety in the name of simplicity and cost, you’re going to be indirectly responsible for encouraging people to maim themselves.

My brother inlaw melted aluminum in a 316 stainless steel container in an electric kiln. The pan developed a hole (due to alloy formation?) and the aluminum ran out of the pan, out of the kiln across the bench onto the floor. Luck was with him since it didn’t hit the gunpowder stored under that bench (he loads his own ammunition)!

I like the story about the furnace It will prevent me from making the same mistake!

There are some more tips in the King of Random update video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l2FuvKTyRMQ