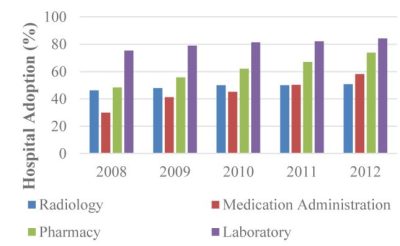

I’ve always considered barcodes to be one of those invisible innovations that profoundly changed the world. What we might recognize as modern barcodes were originally designed as a labor-saving device in the rail and retail industries, but were quickly adopted by factories for automation, hospitals to help prevent medication errors, and a wide variety of other industries to track the movements of goods.

The technology is accessible, since all you really need is a printer to make barcodes. If you’re already printing packaging for a product, it only costs you ink, or perhaps a small sticker. Barcodes are so ubiquitous that we’ve ceased noticing them; as an experiment I took a moment to count all of them on my (cluttered) desk – I found 43 and probably didn’t find them all.

Despite that, I’ve only used them in exactly one project: a consultant and friend of mine asked me to build a reference database out of his fairly extensive library. I had a tablet with a camera in 2011, and used it to scan the ISBN barcodes to a list. That list was used to get the information needed to automatically enter the reference to a simple database, all I had to do was quickly verify that it was correct.

While this saved me a lot of time, I learned that using tablet or smartphone cameras to scan barcodes was actually very cumbersome when you have a lot of them to process. And so I looked into what it takes to hack together a robust barcode system without breaking the bank.

A Barcode Reader to Make a Hacker Proud

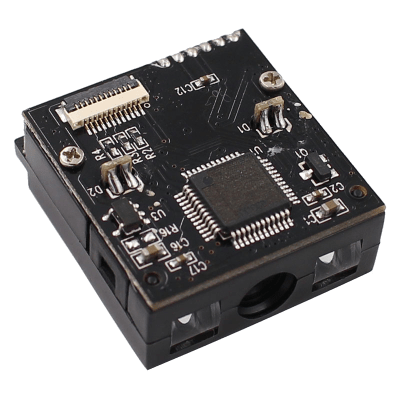

Dedicated barcode scanners cost around $20 USD from banggood or DX and are an obvious solution, but that would be boring. I also wanted a more powerful device: a barcode scanner that could directly connect to the Internet so I could track things centrally online without any further hardware. While the idea was hardly unique, it still stuck with me. Recently, I saw a tiny barcode scanner module (Youku E1005) for sale for $17 USD with no datasheet, and I knew the game was on.

The scanner module itself was very compact, which lent itself well to making a convenient device. It had a generic unlabeled MCU, and a 12-pin ribbon cable connector. The vendor told me it supported Code 39 barcodes (true – but it actually supports many more!), and had USB and TTL output. It was time to puzzle the module out!

Dissecting Barcode Hardware

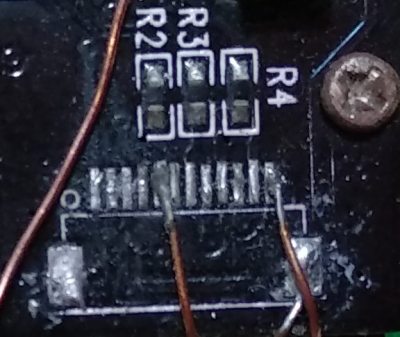

Logically, some of the 12 pins were going to be power, ground, USB data lines, and TTL serial output. Typically these modules are used to build hand-held barcode scanners, so also require a trigger to be pressed to activate the scanner. The first step was to desolder the connector so I could get access to the pads underneath.

The next step was to identify power and ground. Ground was pretty easy since several components were connected to what was clearly a ground plane. The power pin was harder, but there was an IC that looked like a voltage regulator in a SOT-753 package. Given common pinouts, both the enable and the voltage input pins were connected to a single pad.

Having probable inputs for power and ground, I connected 3.3v to the circuit. Nothing happened, which is expected as I’ve yet to find the trigger pin that activates the device. The easiest thing to do was to quickly connect each remaining pad to ground and see if the trigger was of the ‘active-low’ variety. It turned out it was, and the LED of the device turned on to indicate it was ready to scan.

Making Sense of It All

| Pin | Function |

|---|---|

| 2 | VCC |

| 3 | GND |

| 5 | TX |

| 12 | Trigger |

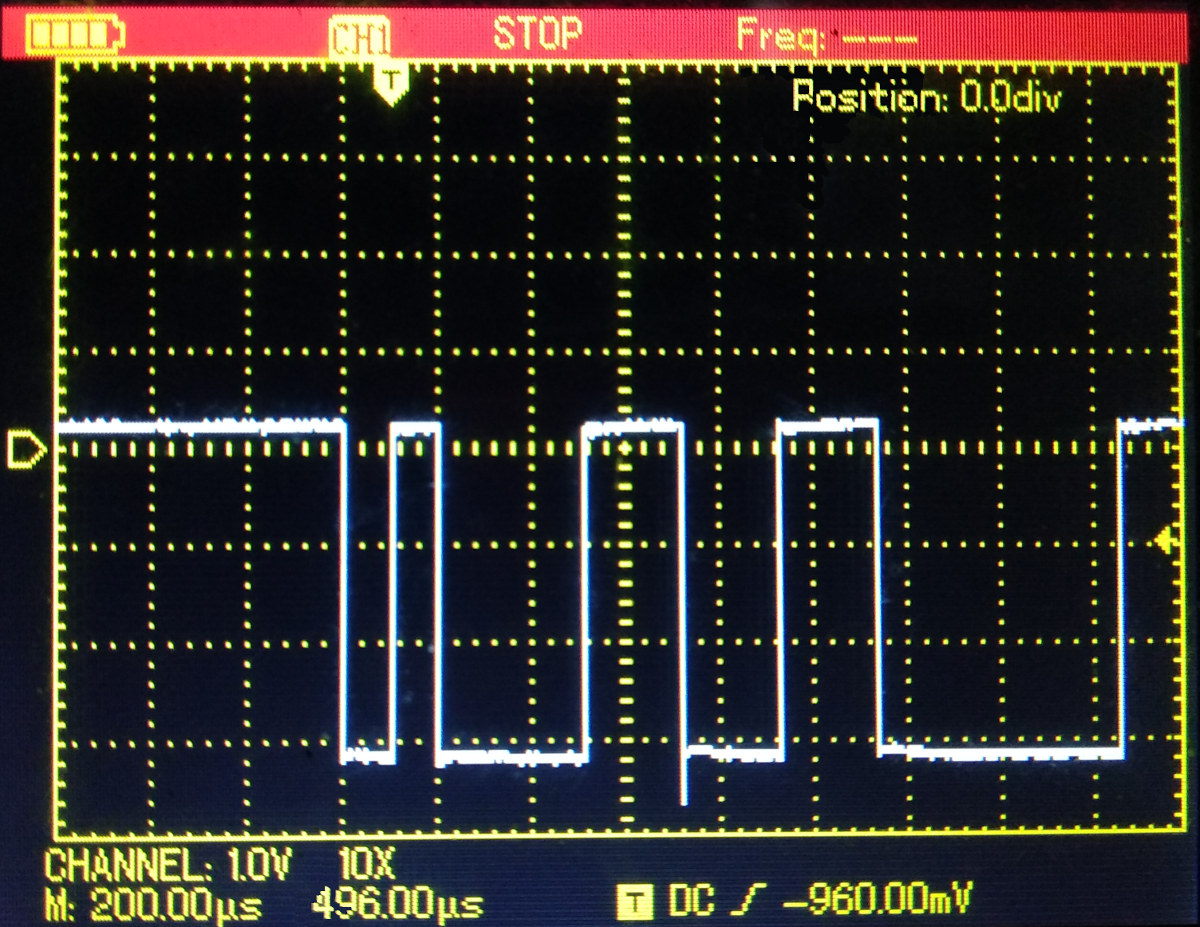

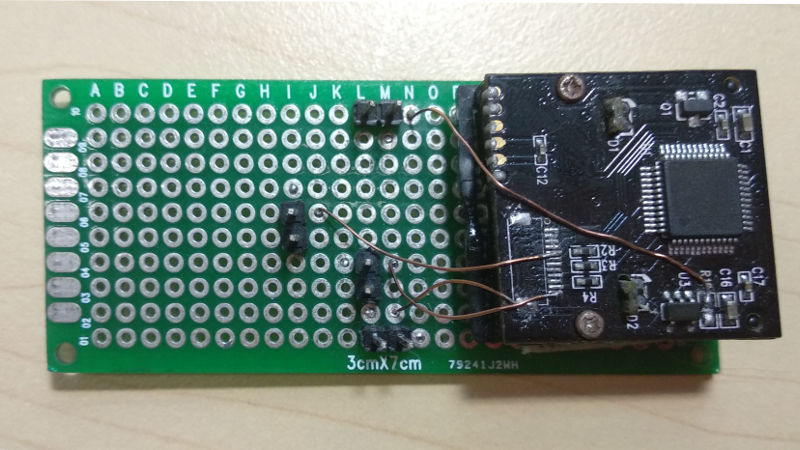

The final step was to find the TTL output. That turned out to be pretty easy now that I could force the device to scan barcodes. I took an arbitrary barcode and scanned it while looking at different pins on my oscilloscope. When I found output, I captured it so I could determine the baud rate later on. The final pinout I found is to the right. The flat cable connector pads were fairly dense, so I soldered wires to components connected to the relevant pads rather than the pads themselves where possible.

After scanning a barcode and capturing the output on my oscilloscope, I saw that the duration of the shortest peak was just over 100μs. That translates to a frequency of a little under 10000 bits per second. The closest common baudrate is 9600 baud, so that is likely our TTL baudrate. Now, we have all the information we need to connect the barcode scanner module to a microcontroller, in our case an ESP8266 running NodeMCU.

Our code will be very simple: Change the UART speed to 9600 baud, and when any data is received concatenate what comes in for the next 150 milliseconds and print it out. Remember to set the baud rate of your development tool (e.g. ESPlorer) to 9600 as well.

-- Setup UART and print something so we know it's working

uart.setup(0, 9600, 8, uart.PARITY_NONE, uart.STOPBITS_1, 0)

print("Scanning")

-- Set up a couple of variables so they're not nil

data = ""

datac = ""

-- This function prints out the barcode data and clears all variables so the scanner can read a new barcode. If you wanted to send the data over MQTT, your code would replace the print statement here.

function finish()

print(datac)

data = ""

datac = ""

end

-- This function concatenates all data received over 150 milliseconds into the variable datac. The scanner sends the data in multiple parts to the ESP8266, which needs to be assembled into a single variable.

uart.on("data", 0, function(data)

tmr.alarm(0,150,0,finish)

datac = datac .. data

end, 0)

This worked quite nicely and was able to read various types of barcode without issue. It would be very easy to connect this to a server on the Internet, either directly via MQTT, or using an Internet of Things dashboard. It would even be possible to implement encryption and authentication if you needed.

Custom Tricks Now Open Up To Us

An interesting fact is that the NodeMCU is capable of executing serial input, so make sure that feature is turned off (the 0 at the end of the uart.setup line). Otherwise someone will promptly drop by with the barcode to the right. The usual precautions apply to the backend as well. You could even filter out problematic characters at the hardware level, which would be nice. Of course if you’re clever this could be a feature and not a vulnerability.

I didn’t have a particular use case for this barcode scanner in mind, but it would be nice to see someone implement it in a cloud Point-of-Sale system for small merchants in Asia to track inventory in a primarily cash-based economy. In effect that would be very similar to the original use of barcode scanners – minus the expensive POS system.

Finally, while at a local convenience store, I saw the perfect project case for this sitting on a shelf. I bought it, and it was filled with candy! Sometimes we live in the best of all possible worlds:

You found 43 barcodes?! I’d kind of like to see a picture of your messy desk. I found 12 on my desk, most of them on my limited array of stationery.

That doesn’t seem farfetched. A few drinks, some snacks, several on each monitor/PC/laptop/docking station/keyboards/mice/power adapters and I’m over two dozen without even looking at books or PCBs.

Heck, the parts of my desk and chair have them.

More, counting corporate asset tags…

There were two pages from a shipping manifest from Arrow reused as scrap paper. That was about 20 of the barcodes. Stationary was a lot of the rest.

There’s about a hundred in one book on my desk, a book for USB handheld scanner with various settings like disable/enable beep, scan on trigger or continuous scan, and various test codes.

-1 Didn’t use a :CueCat (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuecat)

I still have a Cuecat somewhere in my many boxes of junk. Not sure why. I have a lot of junk stored away that I’m sure I’ll never use for anything, and I probably wouldn’t be able to find it even if I wanted to.

Hmm, this might be of interest in food science with commercial extensions to domestic utility as I ‘hear’ its now possible to put some form of barcodes into fruit and vege genes so as the produce grow and develop they express a type of bar code on their skin – not anywhere as contrasted as we expect in our normal visual spectra but detectable nonetheless by appropriate systems across wider spectrum.

ie. As we unpack fruit and vege and of course packaged products too our kitchen IT system logs, checks, offers recipes, tracks perishability, texture etc so the dynamic of food applicability best matches nexus of need vs stock on an ongoing basis…

When you say ‘hear’ do you really mean “read a science fiction novel 20 years ago called ‘The Diamond Age’ where they fantasized’

when the robots automate our leisure activities, what is left for humans to do? We might as ell die off now so we don’t get in the way of the robots cooking our food

Er no. Though I have read sci fi from my earliest days some 50yrs ago but, don’t recall that specific one though it does follow a similar theme from that era – you have prompted me to look it up to read on my next flight unless a cute female sits nearby. When I, as a professionally trained electronic engineer and post grad food scientist with public company experience say I ‘hear’ it means I have come across the issue in more or less confidential commercial circumstances or these days some aspects retrieved from a forum behind a subscribed paywall site. Nothing wrong legally then with me then drawing mention to that in general terms, my choice of language careful so you cannot easily connect it to specifc companies that could well be pursing that. With modern gene splicing with far more targeting and across wider spectra it could be argued to be approaching inevitability and far easier than ever before as aid to food production efficiencies and retail convenience.

As evidenced by articles here, genome sequencing cost is dropping so fast that you might as well just read the DNA direct.

If you are ok with managing consistent aseptic contact ingress issues for sampling sure and add a bit of near infra red (NIR) as well and you could have a very reliable system. For home use though that would be higher cost and more infrastructure than a fast optical system (in commercial use first eg production flow retail scanning) where there is already a barcode to audit trail feedback for the species variants. Much cheaper in mass production to replicate DNA ie. growth with providing data base where expressed NIR matches which product variant. The way tech seems to be moving is approaches to production efficiency and speed first then as cost curves come down for higher quality sampling offers accuracy shifting then into domestic application. All this fine for 1st world with production and distribution efficiencies more import in rest of world long before their economics can support 1st world like dosmetic pleasantries.

Of course the competitor is growing your own food at home, genetics helps there too in respect of robustness, reduced energy cost, also cheap electronics offering controls for consistent outcomes with good nutrition. The only niggle however is good mineral replenishment as it’s turning out to be a key area for humans as mineral content of produce has been dropping since most growers have traditionally focused on speed and size via nitrates negligent of key mineral supplementation in terms necessary mass. Eg. We have ~ 150 Cu based and ~100 Zn based enzymes offering all sorts of necessary health aspects not mere superficial benefits. ie. Metallic enzymes don’t co-operate well in terms of tissue distribution when absorbed as well as not being that bioavailable either. Increased supplementation take years to moderate all sorts of odd deficient medical effects of traditional low mineral intake over decades from supermarket like foods especially when complicated by high sugar intake, artificial flavourings and preservatives.

Barcodes are incredibly useful, in particular if you roll & print your own. I use them to keep track of various collections and stuff i sell online.

“The technology is accessible, since all you really need is a printer to make barcodes.”

And hence why printers will never die out.

The aliexpress store page seems to have the pinout: https://www.aliexpress.com/item/Low-price-CCD-Barcode-Scan-engine-1D-ttl-rs232-usb-small-barcode-scanner/32850591519.html

Thank for that! In hindsight, that would have saved me a little time. I did have fun figuring it out though. I guess that identifies the remaining pins for anyone interested.

Really cool! I enjoyed learning about the hardware of barcode scanners. I work for a company that utilizes barcodes and qr-codes much like you mentioned as a labor-saving device. The company is called Reftab (www.reftab.com) and it allows IT departments to scan laptops and monitors to keep their inventory up-to-date and to track who’s in custody of items.

Very cool stuff

why not 2d/qr too? https://www.aliexpress.com/store/product/2D-Bar-Code-Scan-Engine-1D-2D-QR-PDF417-Datametrix-Barcode-scan-Module-Embedded-Engine-Free/1762603_32893487403.html

Use the flux, Sean! (If your solder joint looks bad, you either didn’t use enough flux or enough heat.)

or he’s soldering with straight tin.

The plastic FFC socket melted when I tried to desolder with my very questionable hot air rework station. It made a bit of a mess. Wasn’t able to clean it up 100% after that. In hindsight I could have clipped off most of the plastic with cutters and prevented most of the issue.

The “Just add more flux!” approach would still have worked I think.

Desoldering is usually made easier by adding some lead solder first. Or, if you have it, Chipquik.

you must have been doing this for a young persons reference books – I have many (over 1000) books that don’t have an isbn. And even more (another 1000+) that have a isbn but don’t have a barcode on them… So I manually have them in a database by author, title, and publisher, and isbn if they have it.. :-)

It was a more or less academic library of management and programming reference books, most fairly new. A few didn’t have an ISBN, but it was an edge case and I entered those manually. I may have just lucked out regarding ISBN adoption I guess.

Yeah ditto, got a few limited run academic published tomes on esoteric subjects, that never got an ISBN never mind a bar code, and some old stuff that predates both. It’s not even very useful when they do have an ISBN, did a random sample the other day to google, and found only one out of 5 that was a straightforward lookup to cataloging card info, the others I was hunting alternate editions and bindings for them. Prospect of automating any thorough cataloging effort looks kind of hopeless.

yep -it’s all my 1950’s and 1960’s stuff that doesn’t have anything (and early 70s) – though many books in the 70s didn’t have barcodes on them (but had the isbn in the inside with the publisher). From memory it wasn’t till the early 80’s that most of the books had barcodes on them, and I’d already been collecting a while.

Of the fact books I’ve got from back then it is surprising how many are still readable ie basic theory on communications, books on project management (ie mythical man month,1975), database design, and even books on usability design (from way before the public internet) that looked at usability of CICS systems, and measuring how fast things had to be to keep users happy etc etc- and on that last one so much of that ‘knowledge’ seems to have been lost and people are only now starting to remember some of the issues that were being discussed 50 years ago…

I also have a lot of 50/60/70s science fiction :-) It’s strange to reread some and realize it is over 50 years old – some of them still work pretty well…

Commercial barcode scanners often learn their configuration settings by being shown special barcodes. These are called “scan tags” in the industry. A typical scan-tag sequence might go like:

ENTER CONFIGURATION MODE

Restore all settings to default

Disable Code-128

Disable Interleaved 2 of 5

Set output interface to USB Keyboard Emulation

Set after-scan key to ENTER

Set max re-scan rate to 200ms

SAVE AND EXIT

The scan-tags are usually in the manual, so any miscreant who wants to mess with a store barcode scanner can just look up the manual, print the config pages, and wave a few across the scanner while nobody’s looking. Disabling the UPC symbology would be pretty rude. Some of the newer scanners won’t recognize the “enter config mode” unless it’s the first tag scanned after a power cycle, which is a crude but effective form of protection against this inane vulnerability.

Anyway, I mention this because it’s sane and useful to be able to configure your scanner through its native interface, perhaps only after hitting a hidden config-enable button inside the cover. But imagine if you could change the MQTT server and auth settings by simply printing out a config page and scanning the codes thereon. Beats dragging out the UART adapter every time!

That’s not a bad idea. My usual approach for passing configuration to the ESP8266 is UDP packets over Wi-Fi, with some type of authentication/encryption if relevant. That requires a separate application on a smartphone or other computer.

With a required config button, what you describe is a neat way to allow user configuration without needing a separate interface. Someone could make a cool little product out of this.

Yeah, some wifi cameras do similar – app on phone generates a QR code containing all the necessary info for the camera to connect. Should be able to do the same thing here.

I’m more interested in Bluetooth stickers on everything, especially licence plates….to help avoid collisions.

Audi drivers can use NFC :-)

pinout of the cable:

1 NC Null Standby

2 VCC DC DC3.3V or DC5V +/-5%

3 GND GND GND

4 Rx Rx Seriële Poort TTL

5 Tx Tx Seriële Uitgang Poort TTL

6 USB_D- Input/Output USB_D-Signal

7 USB_D + Input/Output USB_D + Signaal

8 NC Null Standby

9 BPR Uitgang Buzzer uitgangssignaal

10 LED Uitgang LED verlichting; Uitgang 150 ms wanneer decoderen met succes

11 NC Null Standby

12 TRIG Input Trigger om scan

Can you send me the pic of barcode scanner showing pin numbers

I have a gizmo called the Hiku, that is a WiFi-enabled barcode scanner for tracking groceries, with a voice fallback. Very well designed hardware, unfortunately the company went out of business in May, but it’s surprising no one else has made such a gizmo. Otherwise there are a few barcode scanners like the Symbol CS1504 or Microvision RoV that have batch scanning abilities:

https://blog.majid.info/a-python-driver-for-the-symbol-cs-1504-bar-code-scanner/