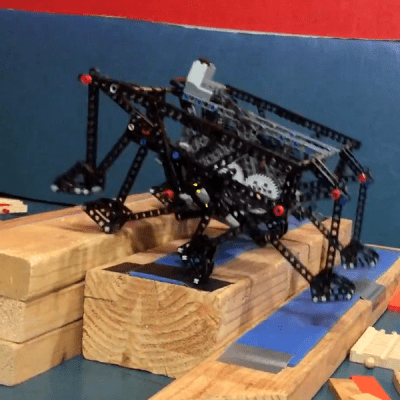

Father-and-son team [Wade] and [Ben Vagle] have developed and extensively tested two great walker designs: TrotBot and the brand-new Strider. But that’s not enough: their website details all of their hard-earned practical experience in simulating and building these critters, on scales ranging from LEGO-Technic to garage-filling (YouTube, embedded below). Their Walker ABC’s page alone is full of tremendously deep insight into the problem, and is a must-read.

These mechanisms were designed to be simpler than the Jansen linkage and smoother than the Klann. In particular, when they’re not taking a stroll down a beach, walker feet often need to clear obstacles, and the [Vagles’] designs lift the toes higher than other designs while also keeping the center of gravity moving at a constant rate and not requiring the feet to slip or slam into the ground. They do some clever things like adding toes to the bots to even out their gaits, and even provide a simulator in Python and in Scratch that’ll help you improve your own designs.

These mechanisms were designed to be simpler than the Jansen linkage and smoother than the Klann. In particular, when they’re not taking a stroll down a beach, walker feet often need to clear obstacles, and the [Vagles’] designs lift the toes higher than other designs while also keeping the center of gravity moving at a constant rate and not requiring the feet to slip or slam into the ground. They do some clever things like adding toes to the bots to even out their gaits, and even provide a simulator in Python and in Scratch that’ll help you improve your own designs.

If you wanted a robot that simply moved, you’d use wheels. We like walkers because they look amazing. When we wrote [Wade] saying that one of Trotbot’s gaits looked animal-like, he pointed out that TrotBot got its working name from a horse-style gait (YouTube). Compared to TrotBot, the Strider family don’t have as much personality, but they run smoother, faster, and stronger. There’s already a 3D-printing-friendly TrotBot model out there. Who’s going to work something up for Strider?

How much do we love mechanical walkers? Enough to post about bicycles made with Jansen linkages, remote-controlled toy Strandbeests both with weaponry and without, power-drill-powered walking scooters, and of course basically anything that Theo Jansen is up to.

If a trip to [Wade] and [Ben]’s website doesn’t get you working on a walker project, physical or virtual, we don’t know what will.

(And from the editorial department of deconfusion: the image in the banner is TrotBot, but it was just too cool to not use.)

That track is very hard for any vehicle to travel, this bot made it look easy, well done!

Being so small and light makes it easy. If the same robot was scaled up 10x, it would fail because it can’t just slip and slide without breaking a leg.

When robots need medical coverage. ;-p

It’s kinda like, when you build a model tank, it can roll around all day long even though the tracks are dragging and pulling whichever way.

When you build a real tank, it needs servicing every few hundred miles because there’s enormous forces on the tracks and rollers that cause metal fatigue and deformation. This is why tanks are actually carried to the battlefield by trucks and trains, instead of driving themselves there. The theoretical service life of a tank track is something like 2500 – 5000 km but in real life you see some pin or rivet popping every few hundred.

Same goes with the robot. If you build a man-sized robot and build it as light as a person, it’s going to have “bones” that are incredibly fragile even when made out of metals and fancy composites. The entire point of biology is that we’re constantly breaking down and repairing ourselves as fast as the damage accumulates, which allows us to have these lightweight yet powerful mechanisms. If you march for a week, you get fractures on your feet. You rest for a couple of day, the fractures are gone. That’s impossible for a robot. They have to be over-engineered to take the strain.

Luke,

thanks for pointing this out – I didn’t mean to mislead people that Strider could perform on rugged terrain at tank-scales like it does at LEGO-scales. I revised Strider’s analysis to make this more clear here:

https://www.diywalkers.com/blog/walking-tanks-prof-shigleys-pioneering-study-of-mechanical-walkers

Wade

AFLAC!

\o/ Geländegängig! \o/

Jetzt noch mit Solarzellen betrieben und dann raus in die Landschaft damit!

Moooment… wie war das mit Hitchbot?!?! :-(

Auf Planeten mit Homo-Sapiens-Sapiens-Infektion kann man einfach keinen Spaß haben… :-(

\o/ Off-road! \O/

Now operated with solar panels and then out into the landscape with it!

Moooment … what about Hitchbot?!?! :-(

On planets with Homo Sapiens Sapiens infection you just can not have fun … :-(

;-)

Besser noch mit mini Nuklearmotor und Selbstoelungsventile.

Somebody call NASA, we need this thing on mars!

That Strider machine isn’t a hack, it’s a breakthrough!

Handles rough terrain much better than a Strandbeest.

Strandbeest were designed to be wind powered and run around on a beach. Not really sure you can compare the two. Sure they are both walkers, but with radically different design goals and intended usage.

True that! And his latest, in the links at the bottom of the Strider piece, are really amazing.

I just had to get “Strandbeest” into the title somehow, b/c people interested in Jansen’s stuff would _really_ be interested in this.

Interesting stuff and very well explained on the website.

Cool!

Double the internet points for Ponoko templates of these bots…

Hackaday…

Remind us of this next September so we can build the LEGO one for Halloween!

It’s kinda like, when you build a model tank, it can roll around all day long even though the tracks are dragging and pulling whichever way.

When you build a real tank, it needs servicing every few hundred miles because there’s enormous forces on the tracks and rollers that cause metal fatigue and deformation. This is why tanks are actually carried to the battlefield by trucks and trains, instead of driving themselves there. The theoretical service life of a tank track is something like 2500 – 5000 km but in real life you see some pin or rivet popping every few hundred.

Same goes with the robot. If you build a man-sized robot and build it as light as a person, it’s going to have “bones” that are incredibly fragile even when made out of metals and fancy composites. The entire point of biology is that we’re constantly breaking down and repairing ourselves as fast as the damage accumulates, which allows us to have these lightweight yet powerful mechanisms. If you march for a week, you get fractures on your feet. You rest for a couple of day, the fractures are gone. That’s impossible for a robot. They have to be over-engineered to take the strain.

Please subscribe to like thanks you