If you have something rusty, you can get a wire brush and a lot of elbow grease. Or you can let electricity do the work for you in an electrolysis tank. [Miller’s Planet] shows you how to build such a tank, but even better, he explains why it works in a very detailed way.

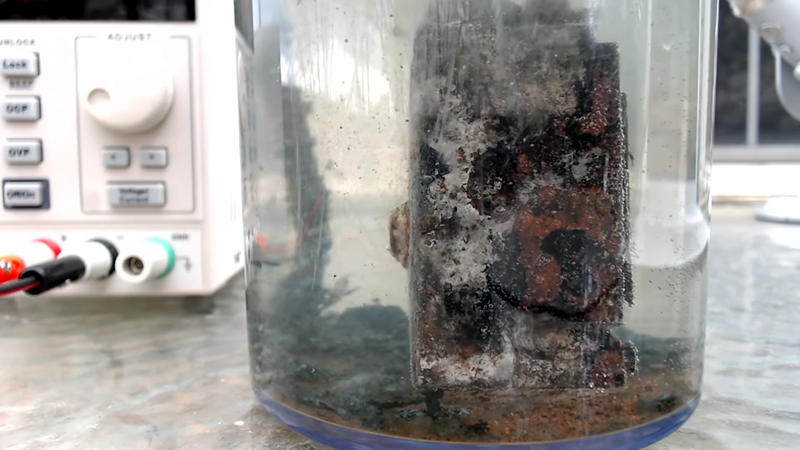

The tank uses a sodium carbonate electrolyte — just water and washing powder. In the reaction, free electrons from the electrolyte displace the oxygen from the rusted metal piece. A glass container, a steel rod, and a power supply make up the rest.

For an example, a rusted sliding door piece was put in the cell. The steel rod became very rusted, of course. The piece came out looking pretty bad because the rust residue was caked on it, but it wiped right off leaving a pretty clean looking piece after an hour. He thinks leaving it in longer would have produced an even better result.

You should not use stainless steel for the steel electrode because stainless contains a toxic form of chromium (although one commenter mentions this is not an issue — we aren’t sure if it is a problem or not). He also warns you to be sure to be outdoors or under ventilation because the process will form hydrogen gas and you don’t want a repeat of the Hindenburg disaster in your shop.

You can use electrolytic action for lots of things. Even drilling holes. Or, you can always make chlorine which is probably just as dangerous as the hydrogen.

rustup self uninstall

:o)

“6 to 12 volts” — sets power supply to 30V

Well, he starts at 10, then goes to 20 and 30 as the current decreases. But yes, he should have said something about this.

Ideally – use a bench power supply with a current limit.

You should not increase the voltage but the current.

Like battery, rust has it’s own voltage to change it’s state.

So, once you got at least this voltage, it will work.

But the more current you put, the more rust you can remove per second.

You should in theory calculate how much current and voltage are needed, but, hey, do whatever you want.

The current consumption is related to the surface to treat by the way.

This is true for all electro chemical reactions, like battery, electroplating, and rush removal.

im not sure but the conductivity of fe2o3 and fe3o4 is wayyyyy lesser than the metal underneath, so i guess its more like generating hydrogen under the oxid layer and pull the rust off. Additionally u use a iron anode that is a Fe2+ ion source and these got also reduced on the surface of kathod metal. guess the metall is looking rough after cleaning which of course is the result of rusting but also of reduction of the iron ions from the solution without additiv. having a look at redoxpotentials its also more likely that u just do hydrolysis rather than reduce fe3o4 or fe2o3 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_electrode_potential_(data_page)) and u are way to high with voltage xD

Sodium carbonate is usually labeled as “washing soda” in the detergent section of your store.

Stainless steel does not *contain* a toxic form of chromium; electrolysis may *form* some Cr(6+) ions from the chromium metal in stainless…but I think it’s more likely that it would form the more stable and far less toxic Cr(3+) ions. If anyone has done electrolysis with a stainless electrode, let us know what color the solution turns as electrolysis proceeds. Orange (not the dull red color of rust) would be Cr(6+), green would be Cr(3+).

Of course, one could use graphite electrodes, making the point moot…

After all the crap settles from running a batch through it’s green here.

I have a 350litre container and de rust large parts in that. 14V, 30-40A.

Keeps the shop toasty :)

I use a carbon anode which works much better. Doesn’t leave all that scum in the brew.

This is more of a proof of theory, an inorganic chemistry class than a practical video. There are alot of videos on this subject that deal with it from a practical standpoint, like not contaminating the reaction with the wrong suspension wires, like copper, use of multiple anode rods or a steel mesh for more efficiency. Ultimately, the voltage is adjusted to produce the optmum current. It will vary with distances, metal area, etc. Too low a current extends the process time. The process is line of sight so the more annode area facing the rusty item, the better it goes.

This is a great way to clean up cast iron. I had several Boy Scout dutch ovens with eagle logos covered in rust. They had been sitting full of rain water for several months before they were discovered. The rust came off leaving a black film which was easy to rinse/wipe off. Then on to re-seasoning. Hours of wire brushing was avoided. I suspended the cast iron in the middle of the bath and was the anode. The cathode was several pieces of aluminum fluorescent lighting fixture linked in parallel around the four sides of a plastic container so that the electrons, and rust, would migrate from all sides.

Sorry, couldn’t tell my anode from my cathode. But I noticed a misspeak in the video. Good article on cast iron cleaning using the process is: http://www.castironcollector.com/electrolysis.php

I prefer to just let my parts soak in vinegar overnight. No work, no risk, except dissolved parts.

Or Coke.

Just don’t use a Mentos anode.

Yep, this is how I strip the rust from vintage vehicle parts. No dangerous chemicals involved and the vinegar leaves the steel looking like a shiny tin can, plus it’s not agressive like electrolysis. The largest thing I have done is a fuel tank, took a few days but came out beautiful. I just buy the cheapest vinegar I can find at the supermarket, use it straight.

You can also use molasses, this is a popular way of freeing up rusted tank tracks and the like, where you can leave them in the stuff for weeks if not months. For instance these frozen Bren Gun Carrier tracks: http://www.mapleleafup.net/forums/showthread.php?t=29512

Fukushima might be a better comparison than the Hindenburg, which did not explode. I thought that one was already well-debunked decades ago?

I did this to clean up some rims for swap-out snow tires. it took 5 days a piece, but I used a 5v 1a wall wart to do the job. I used some old re-rod i had lying around. Left the same black sludge on the rims that wiped off nicely. When i was done, I could read the vin stamped into the steel.