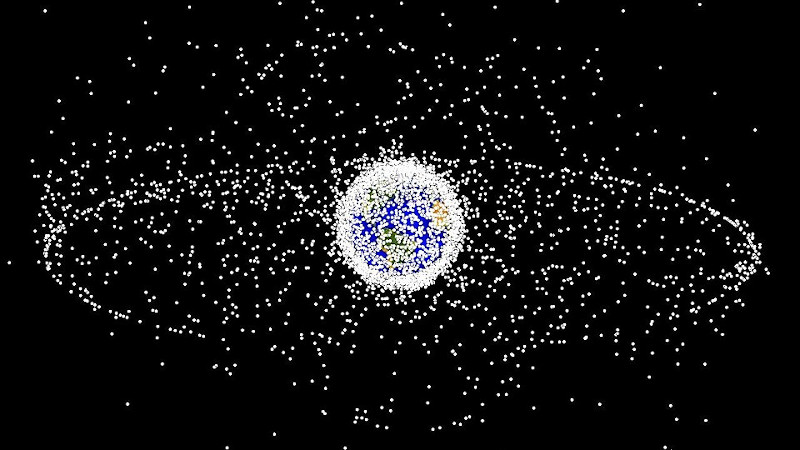

Our skies are full of satellites, more full than they have been, that is, because SpaceX’s Starlink and a bevvy of other soon-to-launch operators plan to fill them with thousands of small low-earth-orbit craft to blanket the Earth with satellite Internet coverage. Astronomers are horrified at such an assault on their clear skies, space-watchers are fascinated by the latest developments, and in some quarters they’re causing a bit of concern about the security risk they might present. With a lot of regrettable overuse use of the word “hacker”, the concern is that such a large number of craft in the heavens might present an irresistible target for bad actors, who would proceed to steer them into each other can cause chaos.

Invest in undersea cables, folks, the Kessler Syndrome is upon us, we’re doomed!

There Is Little As Dangerous As A Half-Truth

It’s worth taking a while to look at some of these stories, because when it comes to technology coverage there is little so dangerous as a half-truth in the hands of people who think Something Must Be Done™. Hacking satellites is an activity with a pedigree that goes back decades, but the advent of Starlink and others like it does not pose any more danger than any other of the craft launched since Sputnik back in 1957. To find out why it’s worth unpicking the sensationalist reports, and peering back in history a little way to uncover some of the real satellite hacking.

The Scientific American article linked in the first paragraph is representative of other similar pieces, and it starts by worrying about CubeSats. These relatively inexpensive satellites are often built from readily available parts which can be analysed for vulnerabilities, the story goes, making them an irresistible target for the Bad Guys.

On reading this half-truth it’s worth wondering whether the author really knows what a CubeSat is, because instead of a large unit with sophisticated propulsion and other onboard systems a Cubesat is a tiny device which simply doesn’t have space for much beyond the barest essential payloads. By and large they tumble through space for the limited time before their relatively low orbit decays, offering invaluable space-based opportunities for their builders but leaving relatively little scope for malicious activities. They lack the equipment to be instructed to switch orbits and smash into other craft, so while one being compromised would be a disaster for its owner it’s difficult to see how the average Cubesat would be a significant prize for an intruder.

They go onto another half-truth to cite the history of satellite hacking as a portent of future doom, under the premise that if it’s happened in the past then it must surely happen again. In some of this they are of course correct, in that there have been many instances of satellites being accessed by unauthorised third parties. But to cite incidents from ten, twenty, or thirty years ago as evidence is akin to citing vulnerabilities in a 1980s UNIX build as evidence of failings in a modern OS. Security comparisons between the two are simply not meaningful. To illustrate this it’s worth taking a look at some of the history of satellite hacking.

The Good Old Days Of Satellite Hacking

Decades ago, to be involved in space technology you had to be a government. The average Joe might just be able to listen to some satellite traffic, but the investment required to set up any kind of ground station was not in any way trivial. Thus satellites were not built with security in mind because it was deemed unlikely that anyone would have the means to access them. This led to many craft carrying open transponders, making them effectively always-on analogue repeaters in the sky.

As technology progressed it became possible to build or acquire ground station components for some of these transponders, and by the 1980s there were tales of shady companies selling transatlantic data links using illicit narrow-bandwidth carriers hidden amid the wideband TV feeds on commercial relays. This type of open-transponder hijack reached a mass-market in Brazil, where the US Navy’s Fleet Satellite Communications System dating from the late 1970s became so widely used as to become almost akin to a CB radio for the vast interior of that country. Even as satellite communications moved into the digital domain it was believed that the high barrier to entry would be enough of a deterrent, so for example the Iridium satellite phone system launched in the 1990s lacked encryption and could easily be eavesdropped upon with an SDR in 2015.

In 2020 though, even the most novice of satellite engineers will be aware of security, and we expect that the likes of SpaceX will not have employed novices. Just as you could steal a 1980s Cosworth Ford Sierra with rudimentary tools but their latest quick Mondeo model has a formidable engine immobiliser built-in, so is it likely to be no walk in the park to compromise any of the current crop of spacecraft. Their citing a satellite hijack story from 1999 as reason to be worried in 2020 is about as valid as worrying about the Mondeo because a child could nick the Sierra; it simply isn’t credible. It’s not that there are not legitimate concerns to be expressed with relation to satellite security, it is simply that inflamatory and shoddy journalism is hardly the way to approach them.

Space debris cloud header image: NASA image / Public domain

Your automotive comparison was excellent! Here in the US I might have been tempted to compare the current generation Mustang with a Fairmont from the late 1970’s (sticking with Ford products for the sake of comparison).

All ford crown victoria cars are keyed alike, so old police cruisers and taxis can be stolen by a 2$ key from Homedepot.

The Crown Vic is akin to the Sierra in the story: it hasn’t been manufactured in almost a decade.

I drove by the Crown Vic factory the other day. It’s gone now. Entirely. Even the buildings have been removed, back to empty field. Amazing. Acres of buildings just scrubbed from the earth. I have no idea where you could even put that amount of material.

I find that sad. Imagine what those facilities could have been used for had they chosen to renovate/lease instead of bulldozing. I live in an old converted factory building myself, and I can tell you from experience that when done right they make excellent apartment buildings. Old factories also make excellent factories, go figure.

Well, with the factory jobs gone there isn’t much call for new apartments… The town was a bit of a one-trick pony, but did do a bit to re-invent itself as a bedroom community. We actually wanted to convert it into a big roller rink & velodrome, but that idea never got much traction, especially with the company that Ford offloaded to facility to.

I can understand taking the buildings down. Taxes… Not in use, then get rid of them. And if they need a new factory. Just build a modern one up to code and built for robotics. Probably easier than retrofit into old buildings anyway.

—

As for the satellites It will me interesting to see if this will actually work reliably for ground service.

That sounds like an incredibly bad idea on Ford’s part, but then it is Ford…

If it’s like what goes on with late 80s and 90s Chryslers and GMs, it’s not so much that they came out of the factory being able to be opened with the same key, it’s that over a few years of wear, the locks and the keys wore down such that over the years more keys opened more locks, until at about 15 years old or so, you’d have a pretty good chance of any opening any.

That’s probably closer to the truth. In the early 80s I had a Kawasaki KZ400 and a Toyota Corona (no, not related to the virus, AFAIK. Nor the beer. And not the Crown Vic either…) Both were about 10 years old. The same key would work in both…

Years ago I accidently opened my brothers Toyota (Corolla?) with my Honda key :-) It was on a still quite dark morning and I obviously had too little coffee. :-)

But I got stopped by the ignition lock and noticed at that moment, that I was in the wrong car :-)

Forgot to mention that the car (and my own) was already quite old also.

I have a 2004 Oldsmobile Alero, just over 15 years old. Some asshole tried to steal it by compromising the ignition switch and ended up leaving in a big hurry. Even 16 years ago they were putting in anti-theft programming. I mean this genius was no hacker, just. brute force attempt. But even when I replaced the ignition, I had to reset the anti theft. I bet those space-X SATs are harder to hack than a Lamborghini.

They aren’t all keyed alike. There are like six different key codes. So while they all aren’t the same, the odds of finding any two that have the same key are infinitely higher than in other cars.

Why is it like this? Because the Crown Vic was a mainstay of fleet vehicles. If you’re a fleet manager with dozens or hundreds of cars and multiple employees for each vehicle, it is so much handier to have only one key to worry about than individual keys for each car. The F-150, Charger, and other cars used as common fleet vehicles don’t have that convenience. With the F-150 I think you can have a maximum of eight keys for each vehicle. They’re expensive keys too where as the Crown Vic’s simple dumb keys can be milled by any hardware store en masse for about a $1.

“In 2020 though, even the most novice of satellite engineers will be aware of security, and we expect that the likes of SpaceX will not have employed novices.”

True, but there’s a couple things. First, security of satellite control, vs security of communications. Two, encryption of communications at the endpoints, basically a space-based VPN.

Right, and thanks to all the awareness of computer security in the OS community, we no longer have worms, trojans, malware, or botnets anymore. Why would satellites be any different? /s

By keeping them as simple as possible. Part of the reason we’re having all these security issues is people’s love of complexity. The more complex the better.

As soon as it starts to move there will be plenty of calls from customers that lost signal, and onboard diagnostic stuff will be phoning home tattling. Same for software hacking systems as there was typical verification replies. A checksum suddenly appearing on your ops console will be concerning. When you have large chunks of money invested, you tend to watch your investments carefully.

‘SpaceX will not have employed novices.’ You make an assertion that cannot be factually checked. If there is an opening, it will be found.

Not quite true, it can be factually checked, though mind I am not claiming it has.

Our current education system, as awful as it stands, is completely based around issuing credentials for validation upon demonstrating the knowledge required to rank one above a novice.

Also note that being above novice does not reflect on skill 1:1, and imho isn’t a great metric to use, but the fact remains it is trivial to verify such credentials that almost by definition mean above novice.

It’s part of the systems whole justification on why you should pay so much to get them

I just have to post this :-) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Captain_Midnight_broadcast_signal_intrusion

“Invest in undersea cables, folks, the Kessler Syndrome is upon us, we’re doomed!”

Yip… up to ±42000 Muskelsats, and there will be competitors too.

So yay!

Let’s say the 42000 only triples.

Where can I bet on seeing the Kessler Syndrome in action soon?

Wait…

Do I hear a happy giggling Mars now?

we have lasers. Cheap, poweful lasers. If the Kessler syndrome makes the orbit unusable, we can just use lasers to nudge debris, so that they eventually end up in the atmospehere…

Has anybody done a serious study of how effective laser de-orbiting might be?

A quick back of the envelope calculation just now (with a fat marker) shows a one megawatt laser running full-time, perfectly aimed at targets of opportunity as they fly over, can impart enough impulse to deorbit a few kilograms per day from LEO.

That little envelope assumes it’s photon pressure alone doing the job, not counting any ablation that might be happening. At 10 kilojoules per square centimeter spread over the 100 second pass, it’s probable things might also get hot enough to give off some gas.

Any one satellite, though, would take 10-100 years of one-pass-per-day treatment to deorbit. You’d need thousands of megawatt-scale lasers spread around the globe to illuminate any given satellite enough to bring it down on the several-month timescale. You could do that to a few hundred targets at a time though.

Any one of those lasers would do a dandy number on a “bad guy”‘s satellite optics, or solar cells, or even electronics. Not to mention the odd errant commercial airplane wandering into a beam…

Don’t think we need them, supposed to still be anti-sat munitions around that are fired at extreme altitude at the top of a zoom climb.

However, the USN do have a bigass beam weapon on a ship too.

Turning one big satellite into a bunch of little ones with an anti-satellite munition is not the way to mitigate a Kessler syndrome…

Kessler syndrome is actually pretty damn unlikely, to the point that it’s basically a half-informed Reddit meme. Especially with cubesats that barely skim the atmosphere and come down in just a few weeks or months. Nothing in so low an orbit (nor anything it may run into) is going to be a problem for long.

And space is friggin huge. It’s the signature quality of space. Even with all the crap we have up there, it’s outrageously unlikely to have a collision. And that unlikelihood scales up vastly as altitude increases. And as I said, low altitudes decay more quickly.

Kessler syndrome basically assumed that space development would progress like we thought it would in the fifties and sixties, with a massive manned presence and the very large, complex craft shedding millions of pieces that accompanies that. Never really played out that way. It’s an extremely sensationalist risk.

Interesting conjecture. On what data and models do you support such a claim?

Kessler’s original paper is from 1978 and contains some solid math models and, despite there being no significant collisions before then, his predictions where pretty much on the money. He showed in 2010 (i.e., after the Iridium event but before Starlink and the other large constellations got lobbed up there), that his models track pretty closely the observed collision rate observed up until then.

His 2010 model assumes 320 satellites launched per year, and predicts a collision rate of about one per month by 2050, and rapidly rising after that. Note that Starlink alone launched 362 already, and is proposing to put over a thousand per year up. With all the other players, we’ll be at ten times the launch rate Kessler assumed.

But at least Starlink isn’t polluting the super-crowded sun-synchronous orbits like Planet Labs and others are doing.

Yes, the notion of there being a sudden catastrophic cloud of debris over our heads is overblown in the popular media, but it’s a real concern and requires real effort to manage and mitigate.

WHAT COULD POSSIBLY GO WRONG?

This (work safe – mouse traps and ping pong balls):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nM-_XaBVneE

Shortly followed by 404 Not Found error messages.

They have them far too close together in the video. Separate them each by a number of miles between the traps and run it again.

Really dumb comparison honestly, just ignorant.

Unrelated to the content, but I have to say it’s a pleasure to read an article by a competent writer. Not to say rest of the HaD complement is bad, but there is some joy in reading a piece where one doesn’t stumble over an awkward construction or spelling error, or (horrors!) a misplaced apostrophe. Thank you Jenny.

Seconded! I was especially appalled by the Sci Am blog post, as that’s not at all what I’ve come to expect from them. So, well done Jenny!

Thirded!

Jenny is favourite HaD author :)

I’m nearly there, but she keeps using the “humble scribe” schtick for the sympathy vote, so I dunno … ;-)

And in case all you others think that was a hint that there’s still a chance you could improve your position by cheap bribes, I’m insulted, they should be rather expensive ones. :-D

I think every writer is permitted at least one foible, that’s mine. :)

(blushes/)

“THEIR citing a satellite hijack story from 1999” … there was a small mistake. And I’m only mentioning it because of this post, it was a great article! :)

There is no error in that sentence. Their writing is faultless. They’re using the word correctly.

In the context, absolutely.

Thanks :) My literacy comes from a unique source, I am still as far as I know the only electronic engineering graduate to have been on the Oxford Dictionaries payroll.

The problem is that it has become cheaper to pollute the skies with space junk than to do the right thing and lay expensive cables.

The stock market really really wants to use this new generation of satellites because the speed of light in glass (fibre optic cables) is only 200,000 kilometers per second (refractive index of 1.5) where as in space the speed of light in a vacuum is approximately 300,000 kilometers per second (refractive index of 1.0) which is roughly 50% faster. They are all about the fastest automated trade times, where a few nanoseconds advantage over time can make you billions.

Even allowing for the 550 km from the ground to the orbital altitude of the 12,000 starlink satellites going through air (refractive index of 1.000293) and the extra 550 km for the downlink and the 8% extra distance travelled between Antipodes and an orbit of 550 km and at sea level. It still works out in the very worst case it is only 14% extra distance, but data will be potentially be travelling 50% faster. If it was restricted by legislation to a minimum altitude of above 3200 km, then suddenly the stock market sees no competitive advantage over traditional earth based fibre optic cables and the funding instantly evaporates.

Today distance and propagation delay are meaningless. The high speed traders put their computer running an autonomous machine learning algorithm right next to the machine handling the trades. Now it’s about who has the smartest and fastest algorithm.

Should be outlawed and the offenders hanged imo

Let me understand this – you refute an article containing actual instances of satellites being hacked, with your own article containing nothing but conjecture.

That leads me to ask the all important question: What are your credentials in the area of cybersecurity or satellite communication protocols?

By your logic, Windows 10 wouldn’t have any vulnerabilities. We all know that isn’t true. Whole new classes of vulnerabilities are discovered on a frequent basis, requiring new classes of testing that won’t have been performed before. Buffer Overflow, XSS, SQL injection. I remember when all of them were new attack vectors, unknown to developers . After 20 years of working in cybersecurity, the only guarantee that I give you is that every system has vulnerabilities. When we’re lucky, no-one knows about them until the White Hats find and patch them. When the Black Hats, or foreign state-funded intelligence agencies discover them first though…

Your article is feel-good filler with no credibility.

Examples of satellite hacking decades ago are not valid as evidence for satellite hacking today. Back then there was no security, no need as satellite ground stations were eye wateringly expensive. Now the satellite engineer’s job has as much need for an understanding of security as the software engineer’s one.

Credentials? I have a really good contacts book, a lot of friends, some of whom work in the satellite business. Do I talk to then? Of course I do, that’s my job as a technical journalist.

if it exists it can and will be hacked expecting anything else is a joke. the only thing these companies can do is hope to slow the time in which that happens but nothing can stop that. (thats even assuming these companies even try that hard as history has shown for profit companies rarely care to put that effort into a project as its not “cost effective”) your articular and your post here shows you’ve run head first into the kruger dunning effect and confused your limited understanding with a deeper knowledge.

I’m “TheBroken”, charged by the FBI in 2009 for stealing satellite TV from Dish Network to the tune of $7B dollars… I can attest to this statement.

+ 1

I’m sorry, but did you actually read the Scientific American article? The examples of Satellite hacking they listed included hacks from 1998, 2008, and 2018 (something about those ‘8’ years, man). While some of the ideas in the article are a little silly, like worrying about crashing cubesats, the fact that you’re just dismissing valid concerns outright doesn’t install confidence in your conclusions.

I’ve always figured there’s somewhere in the NSA or agency that’s remained hidden (maybe as shell companies or companies or well… maybe that’s why there are so many corporations funding by U.S. taxpayers) that has some sort of inductive logical processing application and role that for some known to only a few back door in the know for back door’ing into everything full time job is running processes that iterates every combination and permutation with every piece of hardware and software known and planned to be developed even if never makes it main stream. You’d think they’re trolling the patent office’s throughout the World to seize whatever they can also. Then… for fun and to substantiate more government funding and let people have some perceived freedom… they cause tragedies and market cycles so their guards and corporate rich connections can profit enough to shelter them. What do I know other than what the NSA whistleblowers tell us and just in general how pathetic some are since they job and society commands that from all the wireless brain damaging and then some.

Dunno about all that specifically, but intelligence agencies absolutely hire legions of computer security experts and hackers (yes that’s what the word means damnit, it doesn’t mean some jagoff with a soldering iron. Just let the black hats have it, they deserve it more).

They discover, hoard, and classify tons of software flaws and zero days. Bank them for future projects. Just look at stuxnet; that had SO MANY massive unknown zero days; obviously not the work of a single hacker. Ever been to any infosec con? CRAWLING with spooks. They’re not even hiding; they’re hiring. Looking for talent to add to their pentesting army. But a lot of that talent is used offensively, not just defensively.

snip…”It’s not that there are not legitimate concerns to be expressed with relation to satellite security, it is simply that inflamatory and shoddy journalism is hardly the way to approach them.”

But it is a good way of using ignorance and deference to sell advertising space, click-bait etc.

Forget your Rolodex for a moment. Let’s just concentrate on your journalistic credentials for now.

2018 was just two years ago. That was in the very first linked article.

You just dismissed that as “decades ago” in a pathetically transparent attempt to justify the direction that you took your article. If a story doesn’t go where you want it to, so be it. As a journalist you must follow it anyway, not become part of it. Blatant misrepresentation doesn’t win you any credibility.

Fact: Satellite hacks have happened recently.

Fact: There is no evidence to support the idea that cybersecurity problems are becoming fewer.

Conclusion: We should remain concerned about satellite hacking.

You somehow drew the opposite conclusion by suggesting that hacks are all old, and living in the wishful dream that all engineers today are cybersecurity experts and immune to human error. I’d call that a solid journalistic fail.

You realise that you are misrepresenting jenny’s article in exactly the way you’re criticizing her for, right? She never said we shouldn’t be concerned about satellite security. In fact she repeatedly said that we should.

Amazing