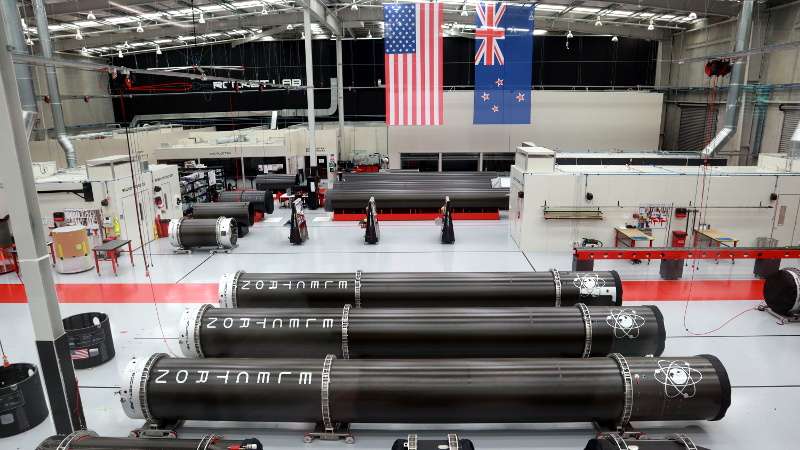

When Rocket Lab launched their first Electron booster in 2017, it was unlike anything that had ever flown before. The small commercially developed rocket was the first to use fully 3D printed main engines, and instead of pumping its propellants with traditional turbines, the vehicle used electric motors that jettisoned their depleted battery packs overboard during ascent to reduce weight. It even looked different than its peers, as rather than a metal fuselage, the Electron was built from a lightweight carbon composite which gave it a distinctive black color scheme.

Packing so many revolutionary technical advancements into a single vehicle was a risk, but Rocket Lab founder Peter Beck believed a technical shakeup was the only way to get ahead in an increasingly competitive market. While that first launch in 2017 didn’t make it to orbit, the next year, Rocket Lab could boast three successful flights. By the end of 2020, a total of fifteen Electron rockets had completed their missions, carrying payloads from both commercial customers and government agencies such as NASA, the United States Air Force, and DARPA.

Rocket Lab’s gambit paid off, and the company has greatly outpaced competitors such as Virgin Orbit, Astra, and Relativity. In fact Electron is now the second most active orbital booster in the United States, behind SpaceX’s Falcon 9. Considering their explosive growth, it’s only natural they’d want to maintain that momentum going forward. But even still, the recent announcement that the company will be developing a far larger rocket they call Neutron to fly by 2024 took many in the industry by surprise; especially since Peter Beck himself had previously said they would never build it.

Leveling the Playing Field

If Rocket Lab is developing a second booster, it stands to reason that they’re looking to take some of the market that’s currently being served by their only real competition, the Falcon 9. Even in its upgraded form, the Electron can only carry 300 kg (660 lb) to low Earth orbit. While there’s a market for these small payloads, their overall operational efficiency would be improved by a larger rocket would allow multiple customers to be served on each launch.

Indeed, in a recent investor presentation, Rocket Lab specifically lists the Neutron as a “direct alternative to SpaceX Falcon 9”, and claims that the rocket’s target payload capacity of 8,000 kg (17,600 lb) to low Earth orbit (LEO) would be sufficient to carry 98% of the satellites currently manifested to launch through 2028. While that may technically be true, the Falcon 9’s 15,600 kg (34,400 lb) LEO capacity puts it in an entirely different league than the Neutron. Calling the two boosters direct competitors would be overly generous to Rocket Lab’s offering, to say the least.

Rather, the Neutron is an exceptionally close match for Northrop Grumman’s Antares. Both stand approximately 40 meters (130 feet) tall, use the same LOX/RP-1 propellants, have identical LEO payload capacities, and are expected to use the same launch pad at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport (MARS) in Virginia. The renders of the Neutron even bear a strong resemblance to Grumman’s booster, though to be fair, the rocket equation doesn’t allow for much in the way of artistic license.

It would be far more accurate to say that Rocket Lab is building the Neutron to directly compete with the Antares, if it wasn’t for the fact that the Antares is only used to loft resupply missions to the International Space Station. Neutron will instead serve as a general purpose booster for commercial and government satellites, and the ISS is unlikely to be on its list of potential destinations. Put simply, while the rockets are all but identical on paper, they serve two very different purposes.

Back to the Drawing Board

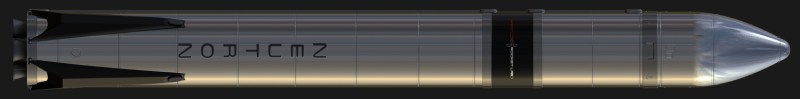

These are early days, and in the grand scheme of things, we know very little about Neutron. The closest thing we have to hard data are some rough dimensions and a handful of renders from the investor presentation. This does seem somewhat troubling for a rocket that will supposedly be flying in three years, but it’s presumed the development of Neutron will be considerably accelerated thanks to the work that already went into Electron. For example, Beck says the avionics system will be largely identical between the two rockets. But even with only a few scraps of information, it’s clear some big changes are on the way.

The most obvious difference is that the fuselage is no longer black, a sure sign that Rocket Lab is moving away from carbon composite construction and switching over to a metallic structure. We can only surmise why they’re making the change, but it seems a safe bet that the cost and difficulty of producing these much larger composite components was more than they were willing to take on. Additionally, as Neutron is being designed with reuse in mind, it could be that a metal structure was seen as easier to inspect and repair between flights.

The investor presentation revealed nothing about the engines that Neutron will use, but we can be sure it isn’t the same 3D printed Rutherford engine that powers the Electron. The smaller rocket has nine engines on the first stage, but in the render we can see Neutron has between three and five nozzles. That means a new, and far more powerful, engine will be used. It would seem that the development program for this engine must already be underway if the company has any chance of meeting their 2024 deadline, but if it is, Rocket Lab isn’t talking.

Finally, we can see that Rocket Lab has been taking close notes on SpaceX when it comes to reusability. Not only are the landing legs on Neutron all but identical to those on the Falcon 9, but the company’s website claims the first stage of the rocket will be recovered after making a propulsive landing on a platform in the ocean.

It’s worth noting that, unlike the Falcon 9, there’s no obvious sign that the Neutron will use deployable grid fins for terminal guidance. As Rocket Lab has demonstrated they can guide the first stage of Electron back down without them, that’s not necessarily unexpected. But Neutron is a far larger vehicle, and it will be interesting to see if Rocket Lab is able to perform accurate landings without these additional control surfaces, or if they’ll have to augment the design as they refine their recovery efforts.

History Repeats Itself

Rocket Lab was founded on the idea of building tiny rockets that were cheaper and more agile than their competition, and marketing them to customers who weren’t content with being second or third rate cargo on traditional boosters. The official line was that they wanted to keep things as simple as possible. But just a few years after starting commercial flights, the company is telling investors they’re building a rocket far larger than its predecessor and even hinting that it might eventually get certified for human flight. There’s an excellent reason that Peter Beck makes a show of literally eating his own hat in the Neutron reveal video.

But still, this situation isn’t without precedent. Just like Rocket Lab, SpaceX got their start with a small booster designed to carry payloads as cheaply as possible. But it wasn’t long before the company realized there was far more money to be made by carrying heavier communications satellites. By 2009, SpaceX had ended flights of the diminutive Falcon 1 rocket so the company could focus their development efforts on the Falcon 9. The rest, as they say, is history.

With the announcement of Neutron, Rocket Lab seems to have reached the same conclusion. Electron has been successful for them, but with the market for satellite constellations rapidly growing, they need a more capable rocket to keep up. The only question now is whether or not Rocket Lab will stay true to their roots and operate both vehicles side-by-side, or if the more capable Neutron will end up making its smaller sibling redundant.

“While there’s a market for these small payloads, their overall operational efficiency would be improved by a larger rocket would allow multiple customers to be served on each launch.”

Didn’t we have a recent story about satellite insurance or lack of?

The vast majority of payloads on F9 rockets don’t come anywhere near the weight capacity. I think that for the business needs of launching payloads, they are direct competitors. It’s like comparing an SUV to a compact for an uber driver. If 95% of your fares are 2 or less people, then the compact and SUV are direct competitors.

Ah but as almost all the cost in launching is the getting out of the atmosphere sharing a F9 launch with multiple other smaller payloads and then correcting the orbit is not only possible but likely. The only reason to use a smaller rocket would be if its launch site is particularly advantageous for the desired trajectory, you need to launch on your timetable so can’t wait to find friends to share the cost of the bigger rocket with or your payload is too heavy (which is challenging to be that heavy, and then not to large for a smaller rocket) to easily find launch partners anyway ..

So in many ways they are direct competitors, except to use your analogy one is a train/Bus that can carry huge numbers including that fat person cheaply and the other a moped/smartcar the fatter payloads won’t fit on anyway, that only make sense to use under the right circumstance… But when it makes sense it really works. So I’m really with the author here, they aren’t exactly direct competition, except in the most basic sense as a method to take something from ground level up a long way…

“Considering their explosive growth,[…]

A logical choice of words from HackADays’s Tear Down writer.

B^)

Space race 2.0 lets GO!

SpaceX, and companies like this are one of the few bright points in the inky abyss that is the current state of the world.

I honestly hope some country says “we’re going to build a base on mars, and it’s going to be our sovereign territory”. That would sure kick things into gear.

They’re looking to “level the playing field” according to your article.

… unlike SpaceX, who recently managed to level the launch field.