Between the 1930s and the 1950s, something sort of strange happened in the United States. The infant mortality rate went into decline, but the number of babies that died within 24 hours of birth didn’t budge at all. It sounds terrible, but back then, many babies who weren’t breathing well or showed other signs of a failure to thrive were usually left to die and recorded as stillborn.

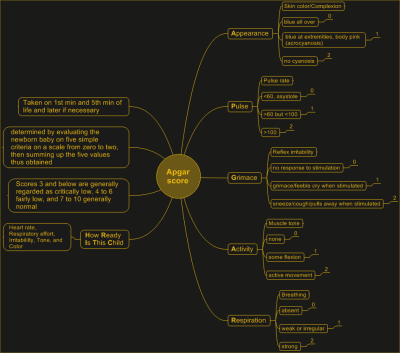

As an obstetrical anesthesiologist, physician, and medical researcher, Virginia Apgar was in a great position to observe fresh newborns and study the care given to them by doctors. She is best known for inventing the Apgar Score, which is is used to quickly rate the viability of newborn babies outside the uterus. Using the Apgar Score, a newborn is evaluated based on heart rate, reflex irritability, muscle tone, respiratory effort, and skin color and given a score between zero and two for each category. Depending on the score, the baby would be rated every five minutes to assess improvement. Virginia’s method is still used today, and has saved many babies from being declared stillborn.

Virginia wanted to be a doctor from a young age, specifically a surgeon. Despite having graduated fourth in her class from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Virginia was discouraged from becoming a surgeon by a chairman of surgery and encouraged to go to school a little bit longer and study anesthesiology instead. As unfortunate as that may be, she probably would have never have created the Apgar Score with a surgeon’s schedule.

Determined to Be a Doctor

Virginia Apgar was born June 7th, 1909 in Westfield, New Jersey, which is about twenty miles outside of New York City. She was the youngest of three children born to Helen May (Clarke) and Charles Emory Apgar.

Her father Charles was an insurance executive, amateur astronomer, amateur inventor, and ham radio enthusiast whose radio work exposed an espionage ring during WWI. Apgar had become interested in amateur radio after hearing someone boast about getting election results before the newspapers could print them. He built most of his own equipment and recorded several radio transmissions around the start of the war, some of which aroused his suspicion. Sure enough, the station they were coming from was owned by the German empire.

One of Virginia’s brothers died early on of tuberculosis, and the other suffered a chronic illness. By the time she graduated Westfield High School in 1925, she was determined to become a doctor. Virginia graduated from Mount Holyoke College in 1929 having majored in zoology and minored in physiology and chemistry. Then she went to Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and graduated fourth in her class in 1933. Four years later, she had completed her surgery residency there as well.

A Medical Wonder Woman

Although Virginia may have had the credentials and the intelligence to go far as a surgeon, there’s one thing she didn’t have — male genes. Allen Whipple, the chairman of surgery at a nearby hospital discouraged her from pursuing a career as a surgeon simply because he had seen one or two women try and fail. Whipple encouraged her to go into anesthesiology — a relatively new field — instead.

He believed that to advance anesthesiology was to advance surgery itself, and he felt she could make a significant contribution. Undeterred, Virginia studied anesthesiology in residency for six months at the University of Wisconsin, and then spent another six months at Bellevue Hospital in New York City.

In 1938, Virginia returned to Columbia P&S as the director of the college’s newly-established anesthesiology division. She had the honor of being the first woman to head any division at the school, and it came with a lot of responsibilities.

Virginia spent the 1940s being an administrator, teacher, recruiter, coordinator, and practicing physician. In 1949, she became the first female full professor at Columbia P&S and stayed there until 1959.

The Apgar Score

Part of her job was providing anesthesia during deliveries, so she spent quite a bit of time around newborns. In the 1950s United States, one in 30 newborns died at birth. Virginia was determined to solve this problem, even though she wasn’t really in a position to do anything about it.

She noticed that although the infant mortality rate was decreasing, the number of deaths within 24 hours of birth stayed constant. As she was in a position to see a lot of births and document trends, she came up with a way to rate newborns’ vitality with a simple five-point matrix.

The Apgar Score is a backronym that stands for Activity, Pulse, Grimace, Appearance, and Respiration. In more revealing terms, the point is to rate the baby’s ability and willingness to move, plus its heart rate, irritability, coloring, and breathing.

Babies are supposed to cry when they’re born — it helps them transition from breathing mucus to breathing air. A non-crying baby would be given a score of 0, while a baby who gasped and sputtered would earn a 1, and a baby with good lungs would rate a 2 in that area. If necessary, all five tests would be run again in five minute increments as long as the baby showed improvement. It worked well, and soon many hospitals had implemented it as standard procedure.

Virginia worked with pediatricians, obstetricians, and other anesthesiologists to establish a physiological foundation for the success rate of using the Apgar Score. To do this, they analyzed babies’ blood chemistry to help correlate the scores with the effects of labor, delivery, and having the mother under anesthesia.

Shining Light on Birth Defects

Virginia left Columbia P&S in 1959 to get a Master of Public Health degree from Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health. She worked for the March of Dimes Foundation from 1959 until her death in 1974, eventually becoming Vice President. She also directed the research program dedicated to the prevention and treatment of birth defects.

During this phase of her life, Virginia also wrote and gave lectures, traveling thousands of miles each year to promote early detection of birth defects and the need for further research. In 1965, she became a clinical professor of pediatrics at Cornell University School of Medicine and taught teratology, which is the study of birth defects.

Honorary Mother of Many

Throughout her career, Virginia published dozens of scientific articles along with several layman-level essays for various newspapers and magazines. She also co-wrote a book called Is My Baby All Right? that explains common birth defects and aims to teach expectant mothers how they can prevent them from happening.

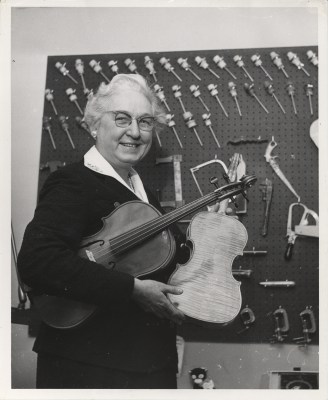

Virginia received many awards over the years, including three honorary doctorate degrees. She never married or had children, but considered music to be a big part of her life. During the 1950s, a friend introduced her to the art of making instruments, and together they made a string quartet’s worth of instruments — two violins, a viola, and a cello.

Virginia devoted her life to helping others live, and she never retired. She died of cirrhosis on August 7th, 1974.

Her father got interested in radio in 1910, so there wasn’t much choice but to build your own.

Excellent story, thank you Virginia.

As a practicing Ob/Gyn of 20+ years, the nurses are the ones tasked with apgars in most facilities and the providers DO pay attention to the scores, though they will obviously normally have a heads up since they are the ones doing the deliveries and can immediately observe color, tone, respirations, movement, etc. The scores are often used in the decision process to decide whether to obtain “cord gases“ to assess baby’s acidemia status and upon having too low scores, to begin to document possible etiologies.

It seems taking a small blood sample, as for a diabetic taking a blood sugar test, would also be a good test. As it is unpleasant (it is a needle prick after all) it would give you information on grimace, activity and respiration (healthy babies would react vigorously, babies in trouble would just lie there) and you would have (a small amount) of blood to test. Has a test like this ever been done?

Newborns ultimately get poked a lot. The benefit of Apgar is that it’s a standardized measurement immediately after birth to guide immediate work up if indicated, unlike initial drops of blood that would still need to be run to the lab and processed. Apgars also give lawyers more fodder for litigation.

Good point about the lab, the Apgar can be done from Cedar Sinai to a clinic in a backwater African village and the Doc just carries it around in his head.

March of Dimes is apt because Virginia was a 10/10!

As an EMT student many many years ago, I learned the APGAR scoring system as part of my training. Curiously, we were only taught the backronym, no mention of the inventor was ever given. Thanks for providing this history.

She even changed her name to match the acronym. That’s dedication.

Then her father to ride her coattails

So then what happens once a score has been assigned? How did it assist in reducing the number of deaths?

Not a medical pro, but watched/helped in both my children’s births. A low score would indicate a possible problem requiring an intervention. Healthy baby goes right to momma. having the metric helps prevent missed problems.

A low score in any area is essentially a low score in every area. One’s skin is the largest organ in the body; if there’s cyanosis anywhere, then iit’s likely the patient is suffering from inadequate perfusion generally.

If a slow heart rate, respiratory rate, or other condition to which the others are secondary can be corrected In as timely a manner as possible, then a child who wouldn’t otherwise be described as healthy and thriving, just might be.

You can’t improve what you don’t measure, or something like that. (Show me your measurements and I’ll tell you your values? Sayings like this are popular to invent I guess) Plus, it’s basically a checklist of systems. Harder to overlook things with a checklist. That’s my “lay person but uncomfortably familiar with neonatology” guess, anyway. (My “wrong kind of Dr” opinion 😉)

Now we just need an equivalent checklist to evaluate the person giving birth, the USA has abysmal deaths-during-childbirth stats…

I would be interested to know the more specific details, if there are any known, about how using the score reduced mortality. There may be some retrospective papers published?

I thought the saying was : to measure is to know.

Can’t fix what you can’t measure. And doctors are competitive. Give them a game they can have the high score in and watch them all try to get that.

But really it’s troubleshooting. ‘Baby daed’ is not as helpful a piece of information for trying to causes of infant mortality as you’d like. But ‘Apgar at 15 min post-birth shows 0 for respiration after 1 at 10 min’ is an indication that 1. the baby got worse in a critical period and 2. it’s maybe the lungs. Did the little bugger aspirate a bunch of goo? Did the doctors check that? Should the ward install goo sucker machines in all the delivery rooms? Ok well Harmony Valley hospital up the hill did that and hey their 15 min Apgar scores are 0.8 points higher than ours so maybe…

What an amazing woman

Ditto! With greater emphasis!

One thing that continues to disappoint me in the medical fields is the lack of system understanding. After my children was born I wondered, why cut the umbilical before the baby starts breathing? It probably doesn’t happen that way in nature, and surely one would wait for the primary oxygen supply to be up and running before removing the bootloader. Right?

So I asked a friend that teaches at a local university and she was surprised, she replied that what I was suggesting is some of the latest theory that is just coming out, with good results, but doctors don’t know about it yet. But try and explain it to a doctor, and the answer I keep getting is we don’t do it that way. Why? Because we don’t do it that way. Doesn’t it make sense? No, we don’t do it that way.

It appears understanding systems and reasoning is an unusual behavior in the medical field.

Give me an engineer that became a doctor any day.

The baby *usually* starts breathing immediately so when you cut the cord is moot. If it isn’t that is a much bigger issues. The cord also doesn’t reach very far, maybe a foot, so it gets cut so you can, you know, hold the baby or bring it to a bassinet or something for resuscitation immediately if needed.

Further, right at birth the placenta begins to separate, and is usually fully released only a few minutes later, thus the term “afterbirth.” so it isn’t doing much to oxygenate baby anyway.

Finally, yes, there is a movement now to place the baby below the level of the placenta and essentially syphon more blood into baby before cutting the cord. “delayed cord clamping” is the jargon.

Yeah, I’m a little peeved when a patient tries to “explain it to a doctor.” Especially when a baby isn’t breathing at birth (!!!) maybe that time isn’t the best to be asking questions like that. I’m certain that if, say, I hired a plumber (or mechanic or engineer for that matter) then stood right there while they were working and asked a bunch of questions while they were working on some stressful thing, they would be less than polite about it. Or at least less polite then like 98% of doctors that I know.

I’m not saying doctors or medicine is perfect, but Obstetrics has come a looooong way. Also I’m not trying to be too much of a jerk- it is your body and your child and your healthcare and of course you should be empowered by that.

Thanks Craig. Always good to hear from someone in the field. And thanks for the syphon data, interesting. I look at it like this, an operation, is like during a car accident. I agree, pretty much, let the driver drive. As they say in the cash in transit industry: when the time comes, you don’t raise to your level of expectation, you lower to level of training.

It was a Csection, not sure about placenta detachment there. I would suspect you have more time.

I only raised the question a year or so later, at dinner with some doctor friends. But I have had quite a few interactions with doctors where a little system analysis could have solved the problem, but no, they relied solely on past knowledge. I suppose it is a natural consequence of seeing the standard problems 99 percent of the time. As an engineer, on average, I have to do something I have never done before, at a guess every 16 hours. So continuously understanding (and designing) new systems is the name of the game.

Here is another example, I came down with the kind of headache that would make you throw up, almost pass out. It got progressively worse while I stood up. The doctors couldn’t figure it our. In hospital for week, xrays, catscans, eventually in desperation a neurosurgeon suggested some cortisone. It cleared and I was back to normal.

2 years later, same thing, this time cortisone had no effect. So I spent 5 minutes thinking about it and suggested it was a low pressure headache caused by a spontaneous leak of spinal fluid from somewhere along the spine that probably heals in a week or so.

I was told no that doesn’t happen, etc etc. But the logic makes sense? Still 5 different doctors, including friends and family told me that can’t be it, it doesn’t happen.

Fast forward another year. Same thing. This time after my week in hospital I simply looked up “low pressure headache” There it was, first page, from Johns Hopkins, rare, but well understood and documented. A leak of cerebrospinal fluid, sometimes spontaneous sometimes on injury. Injury can result from as little as a sneeze.

Spoke to doctors, no one agreed. I also never saw one start their computers to do some research. Very disappointing, apparently only relying on historic knowledge.

2 years later, same thing, I didn’t even bother seeing a doctor, just stayed in bed, horizontal (don’t let the stuff leak) and in week all was good again.

Finally, another year later, back in hospital (I needed the intravenous painkillers), This time a neurologist walked in. Took one look at my chart and said, it was a low pressure headache as a result of a leak of cerebrospinal fluid, stay horizontal for a couple of days and take some caffeine supplements to increase the volume of cerebrospinal fluid. I asked why the others couldn’t identify the cause, he said it was because it was rare,and if they hadn’t seen it fevore, they don’t diagnose for it.

Very disappointing.

What makes it worse, is that it is the same symptoms, treatment etc, for a lumber puncture leak. Which they had seen before. The only difference is the spontaneous part, and they would not join the dots.

I looked at the timelines, noticed i had occurrences in winter. I do a lot of the conceptual design phase in the bath (hours at a time). And more so in winter when it’s cold. Changed my bath for one that is more comfortable on the neck. And have not had another occurrence in the last decade.

A friend once suggested a parallel between doctors and car mechanics and it stuck with me.

Both occupations are based predominantly on past experience and empirical observation. The more cases you have seen and solved, the better you are prepared for future ones. But not all practitioners are created equal and have the same drive to understand root causes, perform full reasoning and ultimately actively grow in their profession. Especially that most of the encountered are dull and uninspiring…

With a poor mechanic suggesting to change parts here and there seemingly at random without correct diagnosis may just be a costly learning experience, going along similar lines as a doctor when patient’s health is at stake doesn’t seem like a brightest idea. Yet it happens ever so often with prescriptions that might just help or waiting for the problem to cure itself.

Ultimately in both cases you’re better off to either find a reputable specialist, or to observe, learn and try to help in diagnosing the problem yourself – just like you did. Somehow attempts to take active part in the diagnosis process seem to be frown upon and dismissed outright in both worlds.

Funny, I’ve always maintained that the difference between doctors and mechanics is that the latter has a service manual.

“lack of system understanding”? We got to almost 8 billion because of better understanding of the system.

Nature and natural aren’t always the solution we want because nature has natural selection and we try every day to bypass it. Giving birth in a controlled environment with proper medical assistance is all about apgar score. Where there was no chance in nature, now there is.

It’s almost the same as with the main topic of the day. Vaccination. It is not natural. Exactly the point. Not being natural is what saves lives.

What can be argued is this: is bypassing nature’s natural selection ok? If it’s possible and it’s yours…yes

True, nature is not always optimal, especially when considering the unnatural environment we live in today. One perfect example is our ‘need air’ sensor. in stead of sensing low oxygen, we sens high CO2. So when, for example you walk into a 100 percent nitrogen environment, you won’t experience the ‘need air’ panic sensation. You will feel fine, then light headed, pass out, and die. As, sadly, some NASA techs discovered the hard way. On seeing their coworkers collapse, few others ran in to retrieve them, and also died.

I had my first life saving operation at age 6 days. So I owe the medical field a lot. But it’s still disappointing that in the US, the 3rd leading cause of death, after heart disease and cancer, is medical malpractice.

Exceptional honor and recognition for Dr Apgar with commemorative US postage stamp issued in 1995: https://digital.sciencehistory.org/works/2801ph41j

Looking for a post here on Hackaday about an archive for medical equipment manuals. I think there is one, but I’m not certain