Neural networks have become a hot topic over the last decade, put to work on jobs from recognizing image content to generating text and even playing video games. However, these artificial neural networks are essentially just piles of maths inside a computer, and while they are capable of great things, the technology hasn’t yet shown the capability to produce genuine intelligence.

Cortical Labs, based down in Melbourne, Australia, has a different approach. Rather than rely solely on silicon, their work involves growing real biological neurons on electrode arrays, allowing them to be interfaced with digital systems. Their latest work has shown promise that these real biological neural networks can be made to learn, according to a pre-print paper that is yet to go through peer review.

Wetware

The broad aim of the work is to harness biological neurons for their computational power, in an attempt to create “synthetic biological intelligence”. The general idea is that biological neurons have far more complexity and capability than any neural networks simulated in software. Thus, if one wishes to create a viable intelligence from scratch, it makes more sense to use biological neurons rather than messing about with human-created simulations of such.

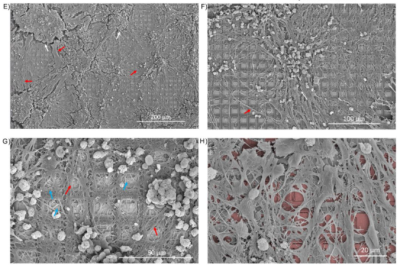

The team behind the project investigated neural networks grown from both mouse and human cells. Mouse cortical cells were harvested from embryos for the purpose, while in the human cell case, pluripotent stem cells were used and differentiated into cortical neurons for the purpose of testing. These cells were plated onto a high-density multielectrode array from Maxwell Biosystems.

Once deposited and properly cultured in the lab, the cells formed “densely-interconnected dendritic networks” across the surface of the electrode array. These could then be stimulated electronically via the electrode array, and the responses of the neurons read back in turn. The result was a system nicknamed DishBrain, for the simple fact that it consists of neural matter essentially living in a petri dish.

DishBrain was put to the test in a simulated game environment reminiscent of the game Pong. The biological neural network (BNN) has a series of electrodes that were stimulated based on the game state, providing the cells with sensory input. Other electrodes were then assigned to control the up and down movement of the paddle in the game.

A variety of feedback approaches were then used to see if the neural network could be taught to control the game intelligently. The primary idea was based around the Free Energy Principle, in which biological systems aim to act to maintain a world state that matches their own internal models. Thus, the “Stimulus” condition feedback loop was designed to provide unpredictable random feedback when the ball was missed by the paddle, and predictable feedback when the paddle hit the ball properly. This method was then contrasted against a silent mode where stimulus was entirely cut when the paddle hit the ball, and a no-feedback mode where no special stimulus was provided relative to the gamestate. A rest mode was also used to get a baseline reading of activity when unstimulated.

The results showed that, initially, there was little difference in game performance between the different modes, with the Stimulus condition performing slightly worse. However, after the first five minutes, statistics showed that under the Stimulus condition, the neural network maintained longer rallies of hitting the ball repeatedly, and was less likely to miss the initial serve, compared to the silent and no-feedback modes. In fact, the Stimulus condition was also the only condition in which the network showed improved performance over time, suggesting evidence of a learning effect. In comparison, the silent and no-feedback modes maintained a relatively flat performance level throughout a full 20-minute test.

The research, yet to be peer reviewed, shows much promise in several areas. Not only is it more evidence that we can successfully grow and interface with neuronal cells, it also provides a platform for a better understanding of how our brains work, on both a conceptual and physical level. If the results are confirmed to be valid, it suggests that the research team essentially managed to grow a very simple brain in a vat, and trained it to control a video game. Professional e-sports players should be on warning! (OK, maybe not yet.)

The paper makes for dense reading, but it shows that there is real potential for biological neurons to be trained to intelligently complete tasks in concert with digital interfaces. While it’s early days yet, in a few decades, you might be topping up your self-driving car with a vial of neuronal growth medium to ensure you can safely make it across the country on your roadtrip without it accidentally merging into traffic. Humanity is just learning how to interface with real biological brains, and it may be that we master that before we succeed in creating our own from scratch!

What could possibly go wrong with putting 1000 kg (~157 stone) of wetware in a box, because you know right well that is what someone at DARPA is thinking.

Bomb 20, return to the bomb bay…..

Let there be light!

From the paper the source material is “cortical cells from embryonic rodent and human”, so probably never going to be larger than the donor material (without cloning). So I wonder could you grow a politician in a box, all it would really need to do is randomly say yes and no. Probably be ones of the finest politicians every, since it would be next to impossible to bribe.

Scaling is down to something as small as a box will take generations to achieve even though evolution seemed to have no problem. I thing evolution and biology took advantage of the fact that the box is mostly empty.

Voyager’s Bio-Neural Gel Packs.

https://memory-alpha.fandom.com/wiki/Bio-neural_gel_pack

If anything, this will make a compelling case for making more accurate simulated neural networks. Playful banter about the future cars aside, there is no chance of biology being interfaced with normal hardware outside of research for a great many reasons.

It appears that your second paragraph was cut off.

Acronymed agency builds a brain the size of a warehouse. After a few seconds of deliberation it decides, the only winning move is, not to play.

Unfortunately, it is completely benevolent and decides that life itself is such an unwinnable game, from which we must all be freed.

By trying to make a content filter/political census/automated weapon system wetware, DARPA’s accidentally going to turn the world into a JRPG

This is interesting work, but they kind of hamstring themselves with grandiose talk about “innate intelligence” and backhanded suggestions that they are making something sentient. I wish we could avoid mixing real, interesting science with hyperbolic extrapolations.

Even the word intelligence does not apply. Neural AI is nothing more than inter-operational matrices like in autocrine cell signalling.

+1 to both

this may not be much use for creating a complex AI, due to the large number of neurons and

keeping the neurons alive would present a host of problems

but

this may be an ideal platform for developing neural interfaces

sticking electrodes into neurons for any length of time has always presented problems

maybe that this is a way to explore stimulating axonal and dendritic synapses to bind to different types of electrical connections, or demonstrate that it cannot be done

This was my take too.

It’s an end run around the difficulty of hooking up electrodes to neurons. Instead, just grow a film of neurons over the electrodes.

“keeping the neurons alive would present a host of problems” this was my first thought

Leave electronic components unattended in a not too extreme environment and they will likely work just fine a few years from now.

Biological tissue?

Not so much…

This is quite creepy to use human embryonic cortical cells

Why is it so different than mice cells ? Because of the – holy crap – word “embryo” ?

Careful with that edge… May end up cutting yourself 8^)

What is the improvement between this paper and this done years ago (probably the method to build the neural network and where they got the neurons):

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn6573-brain-cells-in-a-dish-fly-fighter-plane/