We aren’t ashamed to admit it, but we like clocks. We’ve built quite a few and clock projects show up regularly in the pages of Hackaday. But there is one clock that is among the most famous in the world: Britain’s Big Ben. It has been getting some repairs and the BBC was nice enough to make a video of the giant mechanism.

Actually, the clock is not called Big Ben. That’s the name of one of the five bells in the Elizabeth Tower since 2012. Before that it was the Clock Tower, but everyone always calls it Big Ben. The giant clock weighs over 11 tons and has more than 1,000 pieces. Hard to imagine what it took to build such a thing in 1859.

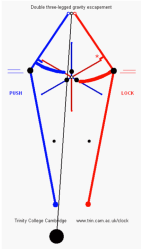

Big Ben itself — the bell — weighs even more than the clock at over 15 short tons. But, of course, we are mostly interested in the clock itself. The design was apparently from a lawyer and an astronomer, both of whom liked clocks. Construction, however, fell to a professional clockmaker and — after his death — his stepson. Dennison, the lawyer, developed a superior gravity escapement that quickly became the standard for future tower clocks and was hailed as one of the great horological inventions of the 19th century.

Big Ben itself — the bell — weighs even more than the clock at over 15 short tons. But, of course, we are mostly interested in the clock itself. The design was apparently from a lawyer and an astronomer, both of whom liked clocks. Construction, however, fell to a professional clockmaker and — after his death — his stepson. Dennison, the lawyer, developed a superior gravity escapement that quickly became the standard for future tower clocks and was hailed as one of the great horological inventions of the 19th century.

The clock now has an electric motor that it can use as a backup. However, it is normally hand-wound three times a week. Winding the clock takes about 90 minutes. Adjusting the clock is also an interesting event. On top of the pendulum is a stack of penny coins. Adding a penny makes the clock run a little faster, removing one slows it down. Each penny is worth about 0.2 seconds/day.

It is great to see such a recognizable piece of 19th century tech get its 15 minutes of fame. Not that the tower isn’t famous, but very few people know what’s inside. The old clock is full of odd stories. The original bell broke when Dennison wanted to test it with a bigger hammer. The new bell made from the old metal also has a crack in it, but still is operational.

You probably aren’t going to reproduce this clock, but you can make something that works on the same principle. Or, try something a bit more steam-punk.

How does adding mass to a pendulum make it swing faster?

It doesn’t. Adding length will though.

https://sciencing.com/affects-swing-rate-pendulum-8113160.html

Shorter pendulums swing faster, no?

Don’t know what Bob is talking about. The shorter the length the faster it swings.

The trick is that the pennies aren’t placed at the center of mass of the pendulum. They are stacked on top of the weight which shifts the center of mass upward by a tiny amount and that makes it effectively a shorter pendulum. Shorter pendulums swing faster so more pennies = clock speeds up.

As someone who, as a kid from the US, had to make sense of the pounds/shillings/pence (£ /s/d) system and its ha’penny/bob etc. derivatives , it’s quite gratifying to see those old pennies still in use along with other more modern ones* (and makes me wonder if the exchange rate of old pennies to new ones would transfer to the world of physics in some fashion).

*https://www.reuters.com/article/us-britain-bigben-idUSTRE5AB5MT20091112

https://www.nbcnews.com/video/big-ben-clock-corrected-using-old-pennies-512956995562

Actually.. If you add mass to top of weight you make it actually shorter pendulum. You are shifting mass center..

In theory, an ideal pendulum wouldn’t swing faster. But a real pendulum… take into account that in an ideal pendulum, the string’s mass is zero, while in a real one it isn’t. So I suspect (I would have to search it, but I’m tired) that adding mass to the pendulum would make it behave more like an ideal pendulum, because the ratio between the string’s mass and the weight’s mass would be smaller, like in an ideal pendulum.

I also presume that elongating the pendulum is not possible due to constraints from the building.

My favorite big clock: https://longnow.org/clock/

thanks i enjoyed that escapement

hands down, on the face of it!

2:14… Brother Maynard, bring up the Holy Hand Grenade!

But will we ever be able to set the time hearing it live on the Bebe? With so many delays coming from web casting now and delays in the studio-transmitter link, I think those days are gone.

It’s definitely no longer a thing in Canada: the National Research Council Time Signal – broadcast at 1pm eastern time every day since 1939 – now goes out at roughly 13:00:10

I will never complain about winding my alarm clock again!

Here’s my much more modest version. Also hand-wound, but I only have to do it once a week :-)

https://photos.app.goo.gl/nzqY5hAE5TF75UMQ6

You have my interest sir. What is that?

It’s the 1883 turret clock in the tower of my local church, which also has 8 bells above the clock. The clock strikes the hour on the tenor bell, the heaviest one – around 850kg.

https://photos.app.goo.gl/bu7haR3rFVUhJx4F9

https://photos.app.goo.gl/qv5MHk7qx2epm1xV8

You confused the heck out of me with the bell business. Maybe revise it to read something like:

“One of the bells in the Clock Tower (Elizabeth Tower since 2012)”

Indeed. But even that could be confusing to someone who didn’t know. The bells were not moved to a different tower in 2012; the tower was just renamed. I am sure she was flattered.