Just a few days ago, MCH2022, a six day long hacker camp in Netherlands, has concluded – bringing about three thousand hackers together to hang out. It was my first trip to a large hacker camp like this, as I’ve only been to smaller ones, and this story is coming from someone who’s only now encountering the complexity and intricacy of one. This is the story of how it’s run on the inside.

MCH2022 is the successor of a hacker camp series in the Netherlands – you might’ve heard of the the previous one, SHA, organized in 2017. The “MCH” part officially stands for May Contain Hackers – and those, it absolutely did contain. An event for hackers of all kinds to rest, meet each other, and hang out – long overdue, and in fact, delayed for a year due to the everpresent pandemic. This wasn’t a conference-like event where you’d expect a schedule, catering and entertainment – a lot of what made MCH cool was each hacker’s unique input.

MCH2022 is the successor of a hacker camp series in the Netherlands – you might’ve heard of the the previous one, SHA, organized in 2017. The “MCH” part officially stands for May Contain Hackers – and those, it absolutely did contain. An event for hackers of all kinds to rest, meet each other, and hang out – long overdue, and in fact, delayed for a year due to the everpresent pandemic. This wasn’t a conference-like event where you’d expect a schedule, catering and entertainment – a lot of what made MCH cool was each hacker’s unique input.

Just like many other camps similar to this, it was a volunteer-organized event – there’s no company standing behind it, save for a few sponsors with no influence on decisionmaking; it’s an event by hackers, for hackers. The Netherlands has a healthy culture of hackerspaces, with plenty of cooperation between them, and forming a self-organized network of volunteers, that cooperation works magic.

Meticulous Complexity Harmonized

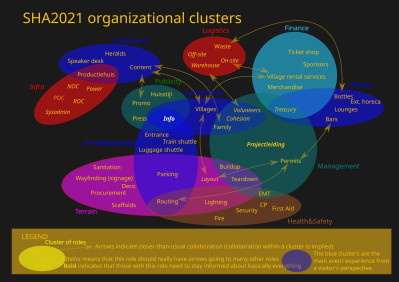

The Summer of 2022 turned out to be a busy time for event organizers – people are getting anxious to go out and have some fun together for once, so it got harder to rent equipment, find services and hire workers. Contracts had to be signed as early as possible, and a “get your ticket early to make camp happen” initiative in the beginning of 2022 has helped crowdfund the initial investment. Preparations wound up, a myriad of people each taking a few crucial roles – this tentative chart might help you get a sense of the complexity.

The Summer of 2022 turned out to be a busy time for event organizers – people are getting anxious to go out and have some fun together for once, so it got harder to rent equipment, find services and hire workers. Contracts had to be signed as early as possible, and a “get your ticket early to make camp happen” initiative in the beginning of 2022 has helped crowdfund the initial investment. Preparations wound up, a myriad of people each taking a few crucial roles – this tentative chart might help you get a sense of the complexity.

As you can see, there’s an impressive amount of things to be prepared. Those of us familiar with event organization know how many things can go wrong in each of these aspects, with grave consequences. Instead, the camp happened without a hitch; in fact, the extra year granted seems to have helped prepare things more meticulously, and even have some fun. The MCH badge itself is a work of art with thought put into its design and purpose, and no doubt deserves a separate article.

Some of that complexity was in helping us, visitors, prepare ourselves. The first thing you’d encounter, even before you start packing up for your trip, is the MCH Wiki page on camping – detailing things that you ought or ought not take, every single aspect and legal limitation one needs to be mindful of. If you ever needed a packing list for your next hacker camp trip, you can safely fall back on the according pages of MCH Wiki – yes, it’s that exhaustive.

Something that pleasantly surprised me is the thoughtfulness of the MCH payment system. Of course, you’ll want a meal every now and then, get a bottle of cold Club Mate at the bar, and perhaps buy some merch too. You might’ve been tempted to just withdraw some notes from an ATM beforehand, like I did. Cash management on such a scale is a real pain, however, as we’ve learned in the intro talk. What fascinated me was the QR code voucher system designed to replace cash for camp’s official purposes, functioning just as well as cash with all the privacy and none of the downsides, and coupled with a card processing system for everyone who had suitable cards — Visa wouldn’t do — and payments were comfortable as ever. At villages, cash still was the only option for purchases and donations; for food payments, I exchanged some of my cash for a QR code and was set.

Something that pleasantly surprised me is the thoughtfulness of the MCH payment system. Of course, you’ll want a meal every now and then, get a bottle of cold Club Mate at the bar, and perhaps buy some merch too. You might’ve been tempted to just withdraw some notes from an ATM beforehand, like I did. Cash management on such a scale is a real pain, however, as we’ve learned in the intro talk. What fascinated me was the QR code voucher system designed to replace cash for camp’s official purposes, functioning just as well as cash with all the privacy and none of the downsides, and coupled with a card processing system for everyone who had suitable cards — Visa wouldn’t do — and payments were comfortable as ever. At villages, cash still was the only option for purchases and donations; for food payments, I exchanged some of my cash for a QR code and was set.

Visit At Least Some Talks

The rule of hacker events applies here – talks get recorded and can always be watched later, but you cannot experience everything else at your own pace after the camp is over. As such, I didn’t visit many talks, limiting myself to about seven – which is not a whole lot, given there were over a hundred scheduled talks across six days. That said, MCH wouldn’t be complete without all the talks – letting us hackers share in the important things we work on, be they impactful, entertaining, educational, or a mixture of these three, and you absolutely ought to visit a few talks at such a camp.

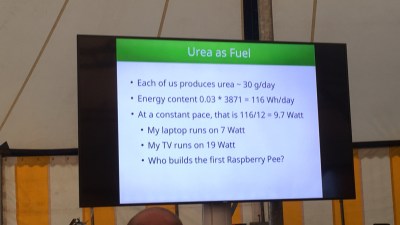

I’m grateful to have been there for a fresh look at Android permission paradigms hiding glaring information leak vectors, an insight into microbes and biofuels, a daring reframing of the way we think about tech recycling, and a journey into side channel attacks on multicore processors. There was plenty of hacking to be witnessed, for all tastes, and most of the videos seem to be already available (YouTube), giving each of us a few dozen hours of hacking stories added to our work playlists.

You couldn’t really limit yourself to the talks, however, as every part of MCH offered so much more – aside from the obligatory CTF and a bunch of badge-related challenges. From workshops and small hacking sessions, to carefully transported art projects and diverse villages looking to show you aspects of hacker life you’ve never experienced before, there was a whole lot to take in. The villages, in particular, deserve a story of their own.

You couldn’t really limit yourself to the talks, however, as every part of MCH offered so much more – aside from the obligatory CTF and a bunch of badge-related challenges. From workshops and small hacking sessions, to carefully transported art projects and diverse villages looking to show you aspects of hacker life you’ve never experienced before, there was a whole lot to take in. The villages, in particular, deserve a story of their own.

It Takes Hackers To Raise A Village

Villages are hacker groups under a physical umbrella of the same tent, from large to small – most open to outside visitors and many private ones. Some villages were thematic, like the lockpicking village that organized regular courses, some were hackerspaces and hackerspace groups arriving in form of a bunch of members and setting up a mini-embassy, and some were friend and coworker groups using their tent as a space to hang out and rest between the camp activities. MCH encouraged you to join a village and help with it, and the various villages on the camp grounds made MCH all that more lively.

As part of a village, you could organize your own sessions – events inviting people to do things at your village, whether for a presentation on hardware hacking basics, a morning run to start a day with some newly found energy, a hands-on exercise on wardriving with ESP32, or 80’s music-backed conversations about ethics in technology. Since it’s possible to bring a bus full of things to a hackercamp like this, many indeed did. That said, you wouldn’t see CNC machines as much as you’d see DJ equipment, speakers, portable grills, fridges, and even a small barrel-shaped sauna that, one would guess, a Finnish hackerspace brought. Of course, you didn’t need to stick to a template.

Milliways is a hacker collective – among other things, they organized a free food stall at MCH; true to its name, accessible to any traveller. Of course, free food doesn’t happen until someone makes it, and every day, you’d see a few volunteer hackers chopping up vegetables and cooking the tortilla filling, chatting amongst themselves as they went about it. In an hour’s time, food would go from “ingredients” to “a meal” thanks to a group of hackers making it happen. It’s not clear to me where Milliways got all the ingredients from – I prefer to assume that, just like its namesake, one relies on some savvy investments.

Retro Computing Village brought a collection of retro systems for us to marvel at, while the Retro Gaming Village had game consoles you could actually spend time playing. The Biohacking Village brought a bunch of medical devices people could pentest, including a glucometer sensor plugged into a potato – which, turns out, has all the characteristics of the human body as far as a glucometer’s concerned. The Food Hacking Base had daily events on own spices and an array of food making equipment, busy on the daily and open to anyone who wanted to share their food making skills, and it makes sense that I’ve met some of the friendliest people there.

Food was a staple in quite a few villages, as you might’ve noticed, and no wonder – it’s one of the quickest ways to a hacker’s heart. A lot of these villages are ongoing projects and will appear at the next camps – be on the lookout. All the villages let everyone bring a part of themselves to the MCH – a requirement for creating a camp people would actually enjoy.

Infrastructure Matters Carefully Handled

Some food trucks were invited, flawlessly functioning toilets and showers were delivered, and there was a live laser-adorned visual show – with audio backing. The MCH camp relies on so much more than that, however – first and foremost, on a tireless team with diverse backgrounds making camp happen. Any visitor could’ve and ought’ve been part of that team – not even by organizing a village or helping with one of the camp’s fundamental aspects, in fact, there was always something you could do to help MCH run smoothly.

The Angel system would be your intro for helping this camp operate, alongside many other hackers like you. If you ever found yourself with a few hours of spare time, the thing to do would be logging into the Angel system and signing up for one of the shifts. Most of these tasks are can be done by anyone, but having options like a driver’s license or first aid training would open extra possibilities for you to be of help. Having neither, I signed up for a runner shift with my friend – being on hold for any random and urgent tasks that you wouldn’t want other volunteers to be distracted by. In the end, there was nothing urgent and unexpected for us to take care of – a testament to just how well the camp was operating on that evening.

Other infrastructure things had to be prepared way in advance. The network infrastructure was a failproof and even somewhat overengineered labor of love – with nary an outage or slowdown in sight, not that you’d find yourself alone with your laptop for extended periods of time, anyway. An expected DECT phone network was running, and the ever-so-helpful medical center was on standby for any issues. Whether it’s the talks, the infrastructure, the villages, or the direction of the camp overall – things were done right.

It All Comes Together

You would make friends here, and in words of someone we met on the first day, you’d find a place where you’d feel like a friend. Whether it’s a common interest, participation in one of the villages or angel activities, partying in the evenings, or the friendly Italians happy to share Grappa with you, there’s no shortage of opportunities to meet a like-minded hacker. Throughout the five days, as I was walking around with my friend, each corner of the camp had its share of random encounters.

We set a few personal challenges for ourselves this camp, such as getting our first experience soldering on a boat (done!), or replacing a 0.4mm pitch BGA to fix our colleague’s laptop (done, and the laptop sprang to life!). That boat was no regular boat, mind you – it turned out to be a fablab boat, aptly named Serendiep, built in pandemic times by an artist collective and therefore equipped with a stage area and means to entertain guests. The fablab area of it fascinated us most – the boat owners were working on things like a compact waste composting unit, aside from all the art-related things, of course.

The camp had so much more prepared for us than what we set out to do initially. ChaosPost – a camp-internal mailing system complete with a giant stack of postcards, – got our attention, and we’ve spent a fair few hours delivering postcards made by other visitors. It also gave us a reason to visit various fields of MCH, areas we likely wouldn’t have visited otherwise. As MCH was happening on the coast of a lake, one of our ChaosPost tasks was to deliver a piece of chocolate to the ferry operating hourly – and we ended up on a short trip on that ferry, to the other coast and back, in company of some lovely people enjoying the scenic route as much as we did.

Later, on the campground, two German guys in an oversized tent with “Free Stuff” written on it attracted our attention – one of them was trying to get rid of a bunch of old equipment taking up space in his basement. Trawling through the boxes, me and my friend started chatting with them about anything, and ended up being invited for some freshly grilled burgers, departing an hour later with quite a few useful bits and pieces we’re now using after the camp’s over. Every corner of the camp had surprises like this prepared for us – people ready to share their stories and discoveries, or perhaps share in the excitement of a some experience.

Later, on the campground, two German guys in an oversized tent with “Free Stuff” written on it attracted our attention – one of them was trying to get rid of a bunch of old equipment taking up space in his basement. Trawling through the boxes, me and my friend started chatting with them about anything, and ended up being invited for some freshly grilled burgers, departing an hour later with quite a few useful bits and pieces we’re now using after the camp’s over. Every corner of the camp had surprises like this prepared for us – people ready to share their stories and discoveries, or perhaps share in the excitement of a some experience.

At different points during the camp, I found myself chasing a small truck I forgot some of our belongings in, chopping vegetables for a Milliways meal, stumbling upon a tent where someone was testing out their experimental software turning datasets into soundscapes, chatting about easy ways to get into USB PD decoding, listening to others’ earnest stories, and every now and then, finding a table with an assortment of beautiful stickers. Occasionally, a small makeshift vehicle would pass us, many covered with LED strips, some visibly converted from hoverboards. These days have given us quite an adventure, full of the appreciable randomness that all the different hackers brought there.

The climate wasn’t at its friendliest – with a two-day heatwave right in the middle of the schedule. Thankfully, things went generally well for all of us, and the medical center was ready to help those who needed it. At night, temperatures would drop, and the camp would liven up. LEDs, flamethrowers and halogen lamps would shine, more than making up for the lack of sunlight. Some areas organized partying with energetic music in the background, others had small quiet meetups and conversations, and with enough distance between these two plus designated quiet areas, those who wanted to sleep could do so comfortably.

Camp Is Over, But Lives On

With all the organizer, volunteer and participant energy put into it, being at MCH2022 was marvellous. A lot of people contributed towards making this camp a worthwhile experience – whenever the next camp around you springs up, you ought to consider making your own contribution, and see it grow into something larger than your effort alone.

While this camp might’ve contained hackers, what happened can’t be contained. Whether it’s talk recordings, pictures, stories, memories, projects and friendships that might spring up from MCH interactions, even if you weren’t there for it, I hope the positive impact of this week-long hacker retreat can linger on our community.

MCH2022 is officially over! Thanks all for a great event!

— MCH2022 (@MCH2022Camp) July 26, 2022

I’d like to thank [WifiCable] and [Peetz0r] for their pictures!

This was really a super cool event! (Well, during the days, it was actually hot)

Thanks a lot to all who helped make it happen.

Oh, yeah, the first time i had the chance to play with 8″ discs. Sadly the Holborn, a CP/M machine with that drive, constantly crashed.

About that payment system… As you say visa did not work. But also so was not master. So basically it was back is square one and cash was only option if you did not have some local no name bank card.

Yeah, sadly, that was the case. Thankfully, there were supermarkets with ATMs nearby, but you did have to look for that info on the wiki.

Hi!

I’m one of the people who were running the payment stuff on site.

We did indeed accept Visa, Mastercard and AmEx for credit cards and Vpay and Maestro for debit cards.

Overall, we had a decline rate of less than/about 1% of all card transactions: some just with a generic “error”, but most returned something like “insufficient balance”, “operation not permitted” (e.g. corporate card that is not allowed to be used at the POS for this specific MCC and/or country) or just plain wrong PINs and “declined by issuer – suspected fraud”.

I would offer you to send me the digits of your cards and look up why your payments failed – but I am aware of how phishy this sounds (and is).

You can however contact me at tickets@ with details of your failed payment and/or a successful one made just after (time, date, which vendor, amount) – that way I can try to find the failed one and extract the issuer/Acquirer response.

Best,

Martin

Ouch that’s embarassing. I remembered supposedly reading there were card limitations on the Wiki and therefore not even trying my card, but now that I tried to find that part again, I cannot find it! It’s actually not impossible that I confused it with other card restrictions I was reading about at that time. My bad – that sentence in the article has to be a wrong assumption, given what you’re saying!

I wouldn’t call the German Sparkasse Group a local no name bank, i could happily pay with my Girocard from them.

And i bet any other EU country bank card would have worked just fine.

True – but for completeness sake: we did not process transactions of visitors from Germany through the Girocard-network. They went – as all other debit cards – either through Maestro or VPay, depending on the co-badge of your card.

A 5m x 3m (day) tent is NOT oversized for two guys…..well, errr, actually it is; but we were supposed to be three guys – a positive PCR kept one at home, though. Still oversized? Yeah…in non-pandemic times we are usually 10+ guys and girls, so that’s why it’s not oversized ;)

And: almost all my free stuff found happy new homes – except for the zwave equipment, thats all still here (back in my basement, waiting for ccc camp next year); the zigbee stuff was all taken after a day or two.

@Arya: Great writeup of a camp that felt like it was the first one in ten years…pandemics suck.

Although I didn’t attend, thanks for taking all the effort to make that stuff available to others.

(Something that I need to do more of in the near future)

your friend kept mentioning that it’s a bit large for two people, so that propagated into the writing ;-P thank you, glad you liked it – and thank you for all the cool things you’ve shared with us, we appreciated that greatly!

in fact, my friend got a WiFi LTE modem from one of your boxes, and thanks to her having it, I could make an important distinction in an article that’s gonna go live in a day’s time, because of having that modem – so there =) and I’ve got a Quectel EC25 card that, turns out, I’m about to do some hacking with ^__^

The Arpenaz 4.1 isn’t that much smaller, 4,6 by 2,6 meter outer shell, but still something you want if you don’t want to feel like an oil sardine. ;)

I couldn’t open the drawing above, but it appeared to me that it was a Venn Diagram Organization Chart. What a neat idea, showing the major actor in one discipline, along with the overlapping skill sets/responsibilities of others.

yes, shows the thoughtfulness of higher-level organization processes! The chart is from here, it’s originally an SVG but hopefully that doesn’t give you too much trouble.

Thanks, much clearer on the link!

Hi, author of that diagram here. I think this, and most other diagrams that people call “Venn” diagrams, would actually be an Euler diagram.

But it’s not that either. It looks like one, but that’s just because I couldn’t fit the actual information in a usable overview in any other way. It should have been a graph with some nodes circled to create clusters, and almost every node in each cluster connected to each other node in the cluster.

One can programmatically generate such a diagram, and I did, but the result is very large and is so unwieldy that it doesn’t provide any insight, just a huge interconnected kludge. So I just began to make a diagram manually, leaving all the edges within clusters fully implicit to keep it simple. I made it in Inkscape and it was way too much trial and error; if anyone can suggest a better (open source) tool for this, I’d love to be inspired!

The end result isn’t pretty but at least communicates the complexity and structure of the organization in a meaningful (but of course incomplete) way. It was mostly intended to make things slightly easier for those who are new to the orga but I’ve heard it’s still rather overwhelming :)

Note, by the way, that it doesn’t show actors or skills, just roles (text labels), clusters of roles (ellipses), and interaction between roles of different clusters (arrows). A role is a named set of responsibilities, that can be fulfilled by a team of people or a single person. To look up the responsibilities for a specific role, click the name in the list at https://wiki.mch2022.org/Roles – Note that the concept of “roles” is just a low level organizational tool; in practice people in the organization will use the higher level concept of “teams” (each team does one or more roles, each role is done by exactly one team).