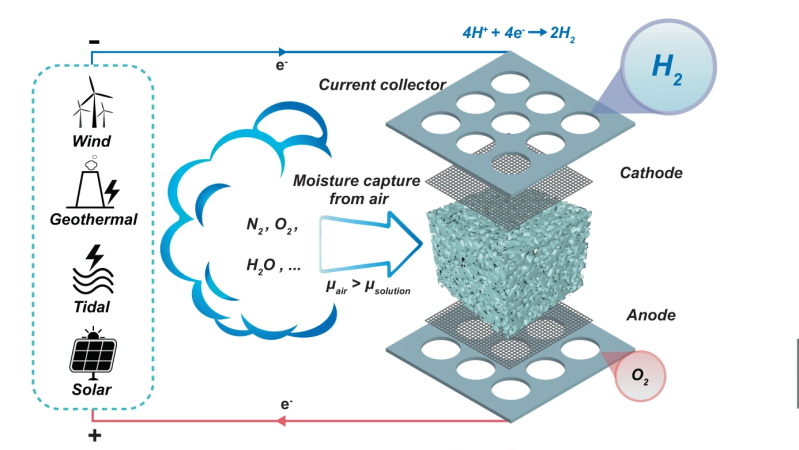

Stored hydrogen is often touted as the ultimate green energy solution, provided the hydrogen is produced from genuinely green power sources. But there are technical problems to be overcome before your average house will be heated with pumped or tank-stored hydrogen. One problem is that the locations that have lots of scope for renewable energy, don’t always have access to plenty of pure water, and for electrolysis you do need both. A team from Melbourne University have come up with a interesting way to produce hydrogen by electrolysis directly from the air.

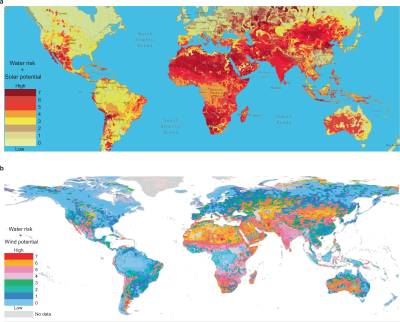

By utilising a novel electrolysis cell with a hygroscopic electrolyte, the so-called direct air electrolysis (DAE) can operate with humidity as low as 4% relative, so perfectly fine even in the most arid areas, after all there may not be clouds but the air still holds a bit of water. This is particularly relevant to regions of the world, such as deserts, where there is simultaneously a high degree of water risk, and plenty of solar potential. Direct electrolysis of saline extracted at coastal areas is one option, but dealing with the liberated chlorine is a big problem.

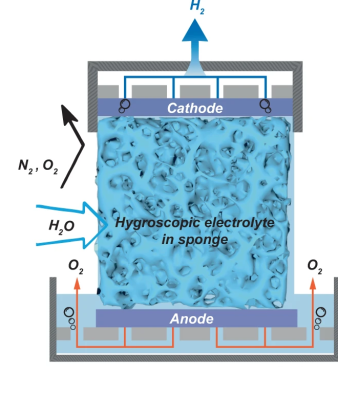

The new prototype is very simple in construction, with a sponge of melamine or a sintered glass foam soaked in a compatible electrolyte. Potassium Hydroxide (alkaline) was tried as was Potassium Acetate (base) and Sulphuric Acid, but the latter degraded the host material in a short time. Who would have imagined? Anyway, with electrolysis cell design, a key problem is ensuring the separate gasses stay separate, and in this case, are also separate from the air. This was neatly ensured by arranging the electrolyte sponge fully covered both electrodes, so as the hygroscopic material extracted water from the air, the micro-channels in the structure filled up with liquid, with it touching both ends of the cell, forming the circuit and allowing the electrolysis to proceed.

sponge fully covered both electrodes, so as the hygroscopic material extracted water from the air, the micro-channels in the structure filled up with liquid, with it touching both ends of the cell, forming the circuit and allowing the electrolysis to proceed.

Hydrogen, being very light, would rise upward through holes in the cathode, to be collected and stored. Oxygen simply passed back into the air, after passing though the liquid reservoir at the base. Super simple, and from reading the paper, quite effective too.

You can kind of imagine a future built around this now, where you’re driving your hydrogen fuel cell powered dune buggy around the Sahara one weekend, and you stop at a solar-powered hydrogen fuel station for a top up and a pasty. Ok, possibly not that last bit.

The promised hydrogen economy may be inching closer. We covered using aluminium nanoparticles to rip hydrogen out of water. But once you have the gas, you need to store and handle it. Toyota might have a plan for that. Then perhaps handling gas directly at all isn’t a great idea, and maybe the future is paste?

Thanks to [MmmDee] for the tip!

Large facilities using this method could help to reduce air humidity in high moist areas. Great for tropical countries.

For people yes but very bad for tropical fauna.

No matter how large the installation is, it’s impossible to change the humidity in a scale large enough to impact tropical fauna.

Oh, yeah? What if the dehumidifier is as big as the moon? Or Jupiter? I bet that would do it.

In those circumstances we’d have bigger problems, figuratively and literally :)

Fine, but good luck getting a permit from the city for that.

Even with an installation as big as the moon.

You will need to power it first. The increase in temperature from the power output and the increase from the latent heat would be so large that there would be no fauna around to be impacted.

If the installation is as large as Jupiter, there would be no tropical area around, so my point stands.

Ah, the belief we humans can’t possibly impact the ocean/sky/other to a relevant degree, as they’re believed to be nearly infinitely big.

That’ll work out just fine, I’m sure.

Just as sustainable fusion won’t lead to heat death of the planet.

I want solar powered A/C that fuels my car.. this might do it… strip the moisture… get H2 as a bonus… use swamp cooler to chill the air… moisture goes back, but pffft, don’t matter. Bunch of panels on the roof for juice, wind turbine too. If you have plenty of storage and oversized system, it would cache energy through the H2 and you’d run H2 fuel cell to feed the house when it was dark with no wind.

Also you’d want an expansion coil in your air handling, so when it was dark, calm and hot, just drawing the H2 from storage would take some of the AC load.

Tropical areas have plenty of rainfall. I include Upstate New York on September 12, 2022.

When February comes, you can have all the snow you want.

I think it would be better if we could electrolyze the water from desalination plants, but maybe it isn’t that good of an idea, even if desert coasts are full of sun, silicium and water.

Though desal plant water is gonna be near the edge, take any more H2 and O out of it and it’s gonna be crusting up on you. So maybe you’d need to dilute it with more seawater.

One step closer to the moisture farms from Star Wars

Sounds like fun, but the hydrogen would to be pressurized for use, storage, and transport. This takes additional energy to the electrolysis. Will the energy gain, even equal the energy used in this process? But, who cares, it’s free energy, right? It’s okay to waste all we want. How useful is pure hydrogen to the average consumer. Will they scrub their daily commute, or shutdown the their heat in winter, if a leak is detected. Like NASA has been doing with Artemis… Lot of potential destruction, even in a car-sized take. Convenient terrorist weapon… Might be an interesting proof-of-concept, but likely limited end use.

> Will the energy gain, even equal the energy used in this process?

By definition not, since the process doesn’t gain energy.

>But, who cares, it’s free energy, right? It’s okay to waste all we want.

Yeah, as long as you don’t consider the taxpayers who subsidize the solar power….

“…Lot of potential destruction, even in a car-sized take[tank]”

Uhm, you do realize that the gasoline in a car’s fuel tank contains about the same energy as a half ton of TNT, right?

And it’s a far safer substance than a tank full of pressurized hydrogen – which is (I believe) far more easily flammable across a much wider range of fuel/air mixtures.

Mythbusters proved it was nigh on impossible to make a gas tank explode by shooting it, I’m not sure I’d take that bet with a tank of hydrogen.

youtube is full of videos of LPG tanks in cars exploding from East Europe / Russia.

And it’s full of plenty of other things exploding too.

Like tesla’s

but on your daily commute how many do you see of either ?

Large scale hydrogen usage will result in damage to the ozone layer. About 10% of all hydrogen produced leaks out into the atmosphere. Once released it rises quickly through the atmosphere where ionizing UV rays cause it to react and deplete the ozone forming O2 and H2O.

Sure sounds plausible, but citation?

For both sentences.

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ja01627a007

https://www.nature.com/articles/news030609-14

Interesting, thanks for providing good references.

Let’s see the math on what “large scale” is.