The true measure of engineering success — or, at least, one of them — is how long something remains in use. A TV set someone designed in 1980 is probably, at best, relegated to a dusty guest room today if not the landfill. But the B-52 — America’s iconic bomber — has been around for more than 70 years and will likely keep flying for another 30 years or more. Think about that. A plane that first flew in 1952 is still in active use. What’s more, according to a love letter to the plane by [Alex Hollings], it was designed over a weekend in a hotel room by a small group of people.

A Successful Design

One of the keys to the plane’s longevity is its flexibility. Just as musicians have to reinvent themselves if they want to have a career spanning decades, what you wanted a bomber to do in the 1960s is different than what you want it to do today. Oddly enough, other newer bombers like the B-1B and B-2 have already been retired while the B-52 keeps on flying.

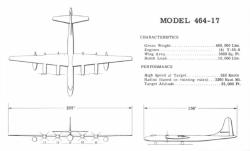

The original proposal for the plane came in 1948. Jet engines were new and not widely considered feasible for long-range bombers because of their fuel consumption. A three-person team from Boeing presented the recently-created Air Force with a plan to build a fairly conventional big bomber with prop engines and straight wings. The Air Force Colonel in charge of development was not impressed. After suggesting that swept wings and jet engines were the future, the team went back to the drawing board in a hotel room on a Thursday night. Their initial attempt was to simply put jet engines on the same airframe.

Not Good Enough

This wasn’t enough. So the team of four drew in two more people — still cramped in a hotel room and redesigned the airframe. The new design had a 185-foot wingspan with a 35-degree angle of the wings and no less than 8 jet engines. A local hobby shop supplied balsa wood, glue, some tools, and silver paint. The result: a 33-page proposal and a 14-inch model airplane. Four years later, that model plane looked almost exactly like the real article.

The plane was able to drop conventional or nuclear bombs and could fly around the world thanks to in-flight refueling. A global circumnavigation took just over 45 hours. Originally, the plane was meant to bomb from high altitudes out of reach of an adversary’s defensive weapons. Once the Soviet Union shot down Gary Powers in a high-altitude U-2, that seemed like a bad idea. But the plane’s versatility allowed it to morph into a low-flying bomber, skimming over targets as low as 400 feet — under the radar in most cases.

The old bird continues to change, proving it can even launch cruise missiles. With an engine refit replacing the 1960-era engine with modern ones, the plane will keep flying through the 2050s. Not bad for a weekend’s worth of work in a hotel room.

The Beauty of the Small Team

I can’t help but notice that things designed by small teams often have a lot to recommend them. Of course, I’m sure that some small team designs fail and then you just don’t hear about them. But consider, for example, the RCA 1800-series processors. By all accounts, these were the work of one person. It’s dated today, and wasn’t a huge commercial success, but if you use its assembly language you can tell that it was well thought out and with an overarching design goal. The CPU was moderately successful, especially in certain applications.

Forth and C started out as the brainchild of just a few people. Ada, on the other hand, was built by huge committees. Even the business community is recognizing that throwing more people on a problem isn’t always making the answer better.

Are They Wrong?

However, I have a slightly different opinion. I don’t think large teams are inherently bad. But consider this. When you set out to build your next robotics project by yourself, you know exactly what you have in mind and what’s important. So the end product is probably very satisfactory for your goal. That’s easy.

If you decide to work with a friend, what happens? Maybe you clash. Maybe you have different ideas and don’t clash, but in the end, nobody is totally satisfied. Or maybe, just maybe, you settle on a common set of goals and design principles and you end up with something good. That can happen in one of two ways. Either one person is very strong-willed and influences the other or — in the best case — collaboration allows both people to influence the other to arrive at a common shared set of goals and principles.

The problem is, even if those outcomes were equally probable, that’s still a 50% fail rate. In half the cases you just clash or do your own thing and don’t get a good result. But I submit that they aren’t equally probable. The strong-willed individual pairing with someone who will acquiesce is relatively rare and finding two people who can truly collaborate in a healthy way is even rarer. So the failure rate is actually more than 50%.

Now scale this up. When you add a third person, things are even less likely to align. Now try 40 or 100 people. Not only is it hard to build a consensus team, but it is also genuinely difficult to keep a large team on a common goal with common guiding principles. It takes a special kind of leadership to make that work, and that kind of leadership is very rare.

So my thinking is that big teams don’t have to be bad. But they do take a special kind of leader that is in woefully short supply. It also takes the right kind of members on the team. We’ve all seen giant open source projects that have strong leaders, and we’ve seen ones that have weak leaders. Nearly all of them have at least a few bad apples that further test that leadership. Leading is hard. There is a fine line between letting things run amok and micromanagement. Not to mention, each increase in size brings more complexity. Communication is harder between 100 people. Given enough people, some number of them are not going to like each other, and there is no way to avoid that.

Can you drive from New York to San Diego without a spare tire? You can. Is it worth trying? Probably not. Can you get a team of hundreds of people to design something that works well? Maybe. Is it worth trying? Only if there is no other choice. Ideally, it seems, the world would be built by individual craftspeople who create something true to their vision. But that’s not always possible. The next best thing is to stack the deck by keeping design teams as small as possible.

Interesting article, thanks for the post! A platform for tech flying frontline for a century is impressive. And in somewhat competitive and high-stakes arena.

To continue the aeronautical theme, Skunkworks was led by Kelly Johnson from WWII through the U2 and to the SR-71 (or RS-71, as it was originally called). His successor, Ben Rich, wrote a book about that, and Johnson’s leadership stands out, but Johnson’s genuis at design stands out more.

I wonder how much powerful a factor technical/topic-specific knowledge and skill is as a component in leadership of an engineering team. It was highly influential at Skunkworks, does anyone have any good counter examples of an effective leader who lead a team and didn’t have significant proficiency in the topic?

I suggest Steve Jobs for effective leader leading team without significant proficiency in designing, and Woz for significant proficiency at designing but not at team leadership.

I thought Jobs was a right asshole and couldn’t manage a team – that it was the team that managed Jobs instead.

Jobs maintained his own secret network of spies within apple. They were exposed after he passed away and most of them were fired. He knew what was going on more than anyone else.

Jobs was a brilliant project manager and for proof positive, you need look no further than the results. You don’t get ipods and iPhones and MacBooks from bad management and you don’t get them from nerdy engineers.

Microsoft is what happens when the engineers control the managers, you get products with stupid names that don’t sell.

Microsoft stuff isn’t a product of engineers, anymore anyway, if it was it might actually bloody work sensibly and be somewhat unified – engineers don’t throw in new ideas for no reason, which is almost all M$ does these days, and when something new is created its all about making it fit into the old clockwork like it might be an original part… MS these days creates a product of bean counters trying to make ever more money and committees..

Oh come now – you have to admire that a multi-billion dollar conglomerate can make an error like leaving vulnerabilities in the damn PrintSpooler and making the task of making app icons a chore. Makes me feel better than even *THAT* much power and money screws things up.

“You don’t get ipods and iPhones and MacBooks from bad management”

Yes you absolutely can get good results from bad management – Jobs, Bezos, and Musk are all fairly well renowned as being assholes to some degree and not the nicest or most forgiving people to work for – but if you’re at a certain level and can pay talented people enough that they’ll put up with your shit for the sake of your company name on their CV, you can beat results out of people.

Ferdinand Piech is another classic example – this story stuck with me:

Once, at an auto show, I congratulated Piech on the superb panel fits of his new cars. He told me, “you want this at Chrysler? Here’s how it’s done: call everyone who is part of body precision into your office. Tell them you want three-millimeter body gaps in six weeks, or they’re all fired.”

((https://www.roadandtrack.com/car-culture/profiles/a28833339/the-complicated-legacy-of-ferdinand-piech/))

For a man who’s company builds such _terrible_ cars, Piech was certainly a huge ass.

I’m sure his granddad would kick him square in the nuts repeatedly for the new beetle alone. Step one of all maintenance tasks on front of car…remove front bumper…seriously. Like an old joke about English sports cars made real.

Never buy a water cooled German car.

You could make a case that General Leslie Groves is an example. With zero nuclear knowledge, he drove the Manhattan project to completion. Of course Oppenheimer set the technical direction.

Maybe as with the Jobs/Wozniak partnership mentioned here by others, the best teams are composed of leaders that overlap but do not compete in the same expertise space.

Lots of examples of leadership pairs that work to accomplish great things. The American “rugged individualism” squashed a lot of it’s publicity and caused a focus on one inspired and gifted leader.

In my personal experience many of the best leadership teams run mom and dad or Mutt and Jeff pairs (a task driver or hard charger with a friendlier listener collaborator), what’s fascinating is when subordinate leader pairs see it and alternate their style as new personalities come on board.

Is that the same General that Richard Feynman wrote about?

He had the largest safe at Los Alomos, but never changed the combination from the manufacturer’s default!

I lived near Mildenhall, UK airbase in the 1950s. B47s would rattle our door knocker as they came over. It was my memory that the B47 came before the B52, in fact, to us from the ground, the B52 looked like the B47’s big brother. I checked, and the B47 did come first. That makes this story a little inaccurate.

Inaccurate how? Nowhere is it claimed that the B52 was the first swept-wing bomber.

Thing started to slide when Boeing management relocated to Chicago. The CEO, at one point said it was nice not to be bothered with engineering issues. Now they have relocated to Alexandria VA so as to better perform their lobbying functions.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2013/01/21/what-went-wrong-at-boeing/?sh=33c695477b1b

https://s3.amazonaws.com/s3.documentcloud.org/documents/69746/hart-smith-on-outsourcing.pdf

Boing bought McDonald/Douglas, which was MBA cancer.

what you did not take in account is the team structure. for example, the B52 was not designed completely by those six persons. they just set the target form and specifications, a huge team of over a hundred people made it happen, calculating and designing sub-assembly’s, trying to match the design goals. what was successful was the chosen set of design goals. they were achievable. that was the success they achieved.

but then again on design team structure. hierarchy is important. and of course communication between departments. look at the Sidney Opera House and what a mess building that was. so external factors are also influential. If the design requirements change during designing, you end up with a compromise and a lot of times with failure beyond your control as a designer.

Also, one cannot forget the benefit they had from the captured german research on swept wings.

of course the B-52 was *also* built by a very large consortium built up of very large teams, in addition to the small team that made the prospectus for the whole project. :)

but i have a slightly different take on the big team / small team difference. on a small team, i think that is a decent description, you have a clash of egos and of visions. that can work out, or it can fail. but it is almost the *only* organizational problem you face on a small team! but on a big team, i don’t think the clash of egos or clash of visions gets amplified…if anything, it fades into the background. i think what happens is that a big team meets a new problem: sunk cost and its cousin, simple bureaucratic inertia. sunk cost is very heavy and it is much harder to overcome than ego. you can’t eliminate six months of committee meetings around a failed premise just by convincing or overcoming the one guy whose ego is on the line.

so there are of course a zillion challenges but one of them is when do you transition from the small team to the big team…you have to do it late enough in the process that the really dead end mistakes have already been avoided. if you do it too soon, you will sink thousands of man-hours into early mistakes that most institutions won’t be able to figure out how to walk away from. the commitee has already scheduled a meeting next week to dig the hole deeper, you can’t walk away now.

The fact that they designed it that fast shows it isn’t that hard to design a plane when you know what to do. However, is it the best design, or just something that has been good enough for the task to this day?

When I see the things we can do today in terms of design and simulation in aeronautics, I don’t think the best designs could be done with 4 people in an hotel room anymore. The world has changed since C and the B-52 were designed.

For the argument against big teams, do you think in a team of 100 people, everyone is equal ? There are people focused on specific parts of the problem, there are the managers, and there is maybe a committee to oversee the whole thing. Maybe the 100 engineers have different visions, but only one vision was chosen, and the 100 engineers didn’t all give their opinion on the whole thing.

When you do a personal project, you do what you want, but maybe not what the rest of the world wants. Teams allow different opinions to compete, and two good ideas have to clash with each other to become better. But if you can’t reach consensus…

“Four years later, that model plane looked almost exactly like the real article.”

afaik it took five year from the A380 project started until the first flight

Airbus studies started in 1988, and the project was announced in 1990 to challenge the dominance of the Boeing 747 in the long-haul market. The then-designated A3XX project was presented in 1994; Airbus launched the €9.5 billion ($10.7 billion) A380 programme on 19 December 2000. The first prototype was unveiled in Toulouse on 18 January 2005, with its first flight on 27 April 2005. It then obtained its type certificate from the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) and the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) on 12 December 2006. Due to difficulties with the electrical wiring, the initial production was delayed by two years and the development costs almost doubled.

> Due to difficulties with the electrical wiring

Lucas?

Well its very much easier to ‘design’ something in the most general terms quickly as the basic concept isn’t that difficult with some understanding of the requirements and current state of the art limitations…

The hard part of a design is actually dotting all the i, crossing all the t and figuring out how you can actually build the thing. Which isn’t the job of a small team for something this big.

The Ford Edsel is a big reminder that design by committee usually tries to do too much and fails spectacularly at most

Complexity.

Or “why modern tech is not recycled”

Look at all the spitfires still flying but the vulcan isnt.

The only thing complex about the B52 are the newer engines and avionics adding in the last couple of decades.

In the case of the Vulcan the problem essentially boils down to weight. Aircraft over a certain size (2730kg) are subject to more regulations than lighter ones in the UK, including the necessity of being supported by a manufacturer. BAE (who have absorbed basically every UK aircraft manufacturer) declined to keep supporting the Vulcan, so it’s not able to fly in the UK anymore.

Plus Spitfires are much more emotive, there’s not many Hurricanes still flying and they’re arguable less complex than Spitfires. They just don’t grab most peoples emotions in the same way.

I flew this plane close to 30 years ago and it was old then! It’s a case study on how to design, along with other projects like the Saturn V. The right people, a clear vision, and a sense of urgency go a long way.

There is grandchildren flying the same B52’s that their grandfathers (and fathers) flew: https://www.minot.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/264580/three-generations-of-b-52-airmen/

Having worked on a lot of teams in various roles, and on a lot of individual projects, I have a take on this.

Dave mentioned it above. Complexity.

There are some things that one person can design from start to finish in a reasonable amount of time… But there comes a point in any large project where you begin to crave experts in different fields.

I could design a complex electronic system and get it built to a high level of confidence… But if it needs software (it will), and I want it to be good software, then I’m going to need help. If it then needs mechanical linkages and enclosure designs, we’ll want a mechanical engineer. If it’s going into space or into a nuclear reactor, or under the sea, we’ll want to involve someone with experience in those applications.

I could perhaps learn how to do it all myself… perhaps… But then it’s at least a 5yr project instead of a 1yr project, and likely still won’t be what I really wanted at the end.

For most projects of any size or complexity above 1 man-year, multidisciplinary teams are essential.

However… As somebody else mentioned, the requirements specification is absolutely key. Get that right and you’re halfway there. Get it wrong and adding people just creates cost and confusion. To get the requirements right you really have to know your application inside out. What problems are we trying to solve here? Why will this be better than the current solution?

I recall that the original IBM PC was designed by a team of three. Sure, someone else probably designed the power supply, and another person the floppy drive. I’m sure that someone from marketing designed the case. The key here is that the essential idea and specifications were done by a small core of people. Once you have the design goal and specifications down, it is easy to go to the larger team and say: “you there, make this part to these specifications.” That part is just basic engineering.

This is why modularity and specifications are good. Look at Linux. When Linus designed it, he did all the work himself. He plugged in some lousy code in different parts to get it to boot. However, because of good specifications and modular design, someone (Linus in the early days, just about anyone now) could come along and replace one chunk of code with something better and have a decent chance of it working.

The reason the B52 is still flying is because of other, significantly more advanced tech available to the Air Force. B52s would not be able to penetrate heavily defended airspace without high tech anti-radar missiles taking them out first. Or high tech ECM and AEW aircraft monitoring and providing support.

They can deliver stand-off but again, high tech cruise missiles, in turn supported by high tech satellite based imagery. Etc, etc

They were quite competent at pulverizing mountains during Desert Storm but not so effective at taking the actual bad guy out.

And replacing the old, inefficient, low tech engines is a bit of a problem due to the size of the nacelles and it has been hard to find modern replacements.

I guess the old airframe is still airworthy.

and they have a lot of those old engines in stock

I worked on the EW systems on my last USAF assignment (B-52G’s at Griffisss AFB)

At that point the older ALT-28 were upgraded to ALQ-155’s by adding an integrated receiver, and we also alled the ALQ-172. At that time the 172 had a cool automated test station, complete with a removable stack hard drive (which was state of the art in 1989).

https://www.quora.com/How-were-B-52s-expected-to-get-through-Soviet-air-defenses-to-their-targets/answer/Slack-Man-1

I beleve they went with a redesigned “drop-in replacement”

https://www.quora.com/Why-doesnt-the-US-Air-Forces-B-52-use-efficient-high-bypass-turbofan-jet-engines-even-though-it-similar-in-shape-and-performance-to-military-transport-and-commercial-cargo-planes/answer/Slack-Man-1?no_redirect=1

Great post – really enjoyed it and the linked article.

A couple of weeks ago B-52 reg 0023 flew over my house. Such a beutiful thing.

I thought at the time how amazing it was that it is as old as me and still in active service. It has certainly worn better over the years than I have :-)

It’s probably had a few more upgrades than you have ;-)

Um, SpaceX? Destroyed the old status quo of how rockets should be designed/tested, built and flown. The big giants Lockheed Martin and ULA are too fat to move swiftly and they have tens of thousands of employees working on their projects, very inefficiently working towards their goals. The result? A big freakin price tag for one of their rockets!

Good article. The PDP-11 was designed over a long weekend and became the most successful minicomputer.

Git was written by Linus over a weekend and, well, you know.

Bill Joy wrote vi over a weekend.

Consider the typical “cost plus contract”. Now think that growing a contract well beyond the original estimate will actually make you more money. With that attitude, failure is an option.

Most NASA and US military contracts become jobs programs. With the jobs distributed over congressional districts of influential congresscritters. Not a sane way to do anything except waste money. SOP for the feds.

See also all the money spent on W Virginia highways because of the dead old trans committee chair/KKK grand dragon congresscritter who’s name escapes me. W Virginia should still not be getting a penny in federal highway funds until things are equalized.

The biggest problem with large teams is communication overhead. This article doesn’t say anything that wasn’t said better in ‘Mythical Man Month’ decades ago.

Also the small team refed wrote the spec, didn’t really design anything.

If the B52 had been replaced on schedule as it should have been, we would not be marvelling at how long it has lasted and how well it was made. It would be just another obsolete airplane. We are only here saying these things because the DOD is too incompetent to figure out a replacement.

The airplanes lasted this long because we treated them with lots of TLC. Any old junk can look great if you take good care of it, ask any museum.

While I agree the B52 could have and arguably should have been replaced despite it still being a very cost effective and functional platform – not everything military has to be super modern, extra complex and cost a few billion a unit.. Lack of replacement can only be done if it lasts fit for purpose.

>The airplanes lasted this long because we treated them with lots of TLC.

In the case of working vehicles not so much – TLC absolutely helps but at some point the act of using it wears out parts its just not possible to repair, its a full on replacement at that point.

With aircraft especially ones from the jet age its usually the air frame fatiguing with use, so that the B52 is still fit to fly does speak to an aircraft design that is impressive for being sturdy enough to last forever, with no design flaws that won’t be noticed for a while (like the square windows debacle) and all while not so overbuilt its incapable of doing the job.

Aluminum has no “infinite stress life” like steel. Every single piece of airframe that is under any stress at all, must be replaced on a regular basis to prevent cracking. There is no “last forever” with aluminum airplanes. This is the “lots of TLC” that I was talking about.

You can only replace bits at all sanely if its possible to get at ALL the parts you may ever need to replace without effectively rebuilding a brand new one from the ground up having taken the old one entirely apart.

That isn’t TLC at that point, its keeping the production line going so you can forever be assembling new ones perhaps with the odd bit of salvage from the old ones thrown in – The B52 can be kept flying because the parts that ever need replacing are actually replaceable relatively easily – its not easier to melt the damn thing down and make an entirely new one every time a part fails the check or ages out. Which just isn’t the case for many aircraft.

No. When a B-52 spar passes it fatigue life they dust another off out of the desert and move the avionics and engines to the new old airframe.

It’s the junkyards keeping B-52s alive.

When buying a car to keep for a long time always buy a popular model.

Also no stupid bad parts (e.g. JATCO CVTs, anything German after 2000, stealth coatings requiring climate controlled hangers etc etc). Those things are just bic lighters, disposable by design.

You have this to consider…

https://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/systems/b-52-life.htm

More people, more problems. Especially if there is no organization or idea who is doing what. Managing technical problems is easy. Managing people is not.

Re B-52. It obviously is still in service because it’s more modern ( having higher number) than B-1 and B-2. ;)

There are things that simply can’t be done by a small team like designing an FPSO, but I definitely agree that innovation almost always comes from a small team. The thing I’ve seen in real life is that with modern project management, there is no product development, just a large team who is struggling to build something salesmen have pre-determined against an insufficient budget and impossible timeline. Not the best way to bake a cake. There’s a pretty good book on this “The Mythical Man Month” which brings up that unless streamlined to small teams flowing to larger groups, the intercommunication within a group is N factorial the number of people in the communication cohort. Communications failures and delays and project ownership or lack thereof are the greatest performance risks to a project IMHO.

“newer bombers like the B-1B and B-2 have already been retired”

Wrong in both cases.

I was very surprised to read that these aircraft had “already been retired”. The Wikipedia says that the planned retirement date for the B-1B is 2036: not quite yet. The B-2 is scheduled for replacement in 2032.

I absolutely love History’s telling and lessons. Let the Morons be famned for becoming Superstitious fools cursed to repeat history!!! Thank you very much gor telling and reminding us all of what and who went before us all. Stay well all.

Braben and Bell coded Elite by themselves, created a massive hit and a new type of video game, all done by 2 people.

If you do it yourself, it is always done exactly how you would do it. That’s priceless. Also as I get older, re: teams, planning and meetings. More and more I find myself saying “if we just went and did it, it would be done already.”

The author of the article is engaging in a little revisionist history: The last F in BUFF does not stand for “Fellow”…

And Al, I think your metaphors may need updating: Anybody driving from New York to San Diego in a car made in the last, oh, 20 years doesn’t have a spare tire.

Maybe your modern metaphor could be “Can you drive from New York to San Diego without a cellphone? You can. Is it worth trying? Probably not.”

Though I guess it’s also true that almost everybody driving from New York to San Diego in a car more than 20 years ago didn’t have a cellphone. So ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

“Fellow” was also used, especially around the wives and kids.

The author wasn’t being revisionist, those who used the “other” wording were doing the revising.

The problem with a committee of any particular size is that the chair or leader has to resolve conflicts. Often these conflicts are not over right or wrong, but of different goals or different ideas of what could be done. The more people you have on the committee the more ideas tend to float around and it gets harder and harder for a leader to say “Enough!”

This is why Engineers shudder whenever someone mentions a design committee. What you typically get is a baroque design that doesn’t do anything particularly well. The most well known aircraft were the opposite. They were designed for one thing. The B52, the A10, the U2… these aircraft still fly today because the idea behind the design was limited and the design was focused on doing a single mission well. Meanwhile, look at the F35, which doesn’t do anything particularly well. My prediction is that in ten years everyone will be eager to either significantly change the F35 for a single use/mission or get rid of it.

Notahack.

Also glorifying a machine that has killed thousands of innocent civilians.

Jobs lucked out by having Flash RAM become available at just the right time.

Price’s Law – “The square root of the number of people in an organization do 50% of the work. As an organization grows, incompetence grows exponentially and competence grows linearly.” – Derek John de Solla Price, physicist and information scientist, credited as the father of scientometrics