Hackaday has been around long enough to see incredible changes in what’s possible at the hobbyist level. The tools, techniques, and materials available today border on science-fiction compared to what the average individual had access to even just a decade ago. On a day to day basis, that’s manifested itself as increasingly elaborate electronic projects that in many cases bear little resemblance to the cobbled together gadgets which graced these pages in the early 2000s.

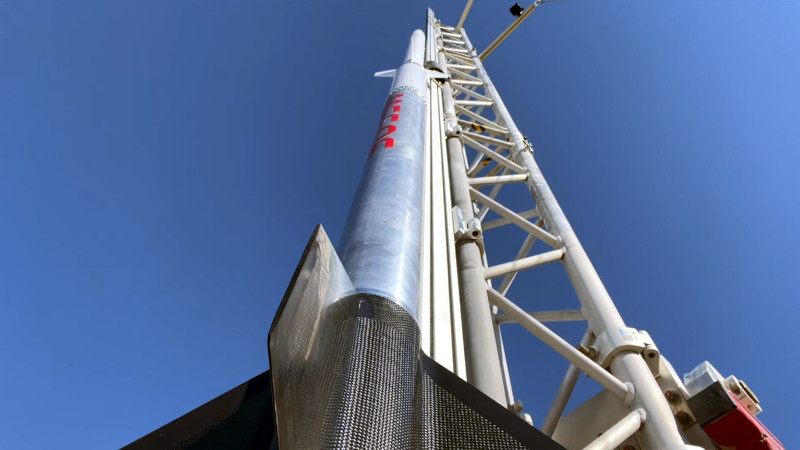

But these gains aren’t limited to our normal niche — hobbyists of all walks have been pushing their respective envelopes. Take for example the successful launch of MESOS, a homebuilt reusable multi-stage rocket, to the very edge of the Kármán line. It was designed and built by amateur rocket enthusiast Kip Daugirdas over the course of several years, and if all goes to plan, will take flight once again this summer with improved hardware that just might help it cross the internationally recognized 100 kilometer boundary that marks the edge of space.

We were fortunate enough to have Kip stop by the Hack Chat this week to talk all things rocketry, and the result was a predictably lively conversation. Many in our community have a fascination with spaceflight, and even though MESOS might not technically have made it that far yet (there’s some debate depending on who’s definition you want to use), it’s certainly close enough to get our imaginations running wild.

The bulk of the conversation was about, as you might have guessed, rocket fuel. Or more accurately, the different types of propellants available for these sort of large amateur rockets. While liquid fueled rocket engines hold incredible promise in terms of performance, they remain a considerable engineering challenge for the home gamer. Plus as Kip explains, solid rocket motors offer a higher propellant density, meaning you can get more energy into a smaller vehicle.

For MESOS, Kip says he used a propellant known as ammonium perchlorate composite propellant (APCP). While the composition naturally varies depending on the application, this family of propellants is the same as you’d find inside the Space Shuttle (and now SLS) Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) or an aircraft ejection seat.

For MESOS, Kip says he used a propellant known as ammonium perchlorate composite propellant (APCP). While the composition naturally varies depending on the application, this family of propellants is the same as you’d find inside the Space Shuttle (and now SLS) Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) or an aircraft ejection seat.

It’s powerful, reliable, and somewhat surprisingly, not terribly difficult to mix up at home. As the name implies, the primary ingredient is ammonium perchlorate, which at least in the United States, is not a regulated substance. To that you add fine aluminum powder, and then a binder to hold it all together. Kip didn’t give the exact formula for his secret space-scraping sauce, but did mention that the rubberized binder makes up approximately 18% of the mixture.

This being Hackaday, there were also questions about the electronics aboard MESOS. Unfortunately for those hoping to hear some juicy details about the rocket’s custom flight computers, Kip revealed that MESOS is using off-the-shelf units. Specifically, a Featherweight Raven 4 and a Multitronix Kate 3.0. There were a pair of modified GoPro Hero 9s onboard as well, but he actually off-loaded the modifications to a Canadian company by the name of Backbone. Of course, who can blame him for not wanting to tackle custom electronics on a project like this? When you’re literally building a rocket from scratch, there’s already more than enough components that need to be designed and fabricated.

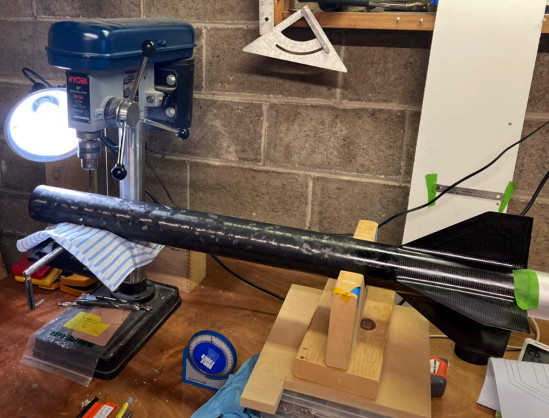

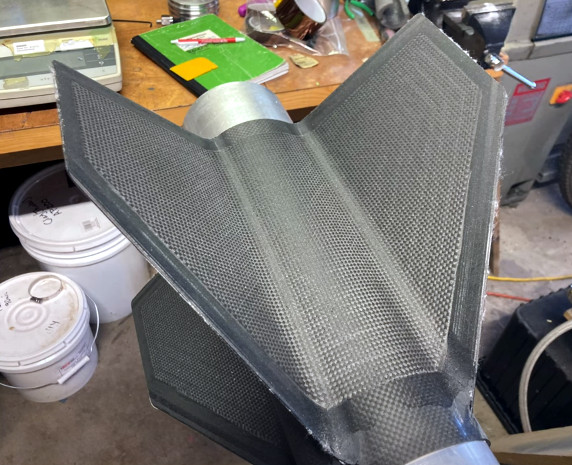

To that end, Kip did provide some interesting details about the rocket’s construction. The engine mounts were machined out of 6061 aluminum, while the airframe itself is largely fiberglass and carbon fiber composite. The carbon is wound around the tubular structures and nosecone, but the fin section necessitated a complex multi-step layup.

To that end, Kip did provide some interesting details about the rocket’s construction. The engine mounts were machined out of 6061 aluminum, while the airframe itself is largely fiberglass and carbon fiber composite. The carbon is wound around the tubular structures and nosecone, but the fin section necessitated a complex multi-step layup.

Judging by the state of MESOS when it landed, we’d say it’s certainly built tough enough — though Kip does mention during the Chat that he might need to revisit the protective coating on the second stage’s fins. With an ascent velocity beyond Mach 4, the leading edges were subjected to temperatures as high as 704 °C (1,300 °F), which the carbon composite construction wasn’t overly thrilled with.

We want to thank Kip Daugirdas for taking the time to talk with the Hackaday community about his incredible accomplishment. He really pulled the curtain back and shared some fascinating information about the project and rocketry in general, so if you’re at all interested in the hobby, we’d suggest reading through the complete transcript. We can’t wait to see MESOS take to the skies again, and hope it finds itself on the other side of the Kármán line before too long.

The Hack Chat is a weekly online chat session hosted by leading experts from all corners of the hardware hacking universe. It’s a great way for hackers connect in a fun and informal way, but if you can’t make it live, these overview posts as well as the transcripts posted to Hackaday.io make sure you don’t miss out.

Um not sure if the shuttle solids were categorized as apcp, not a chemist but instrumentation tech, we were told while working at Edwards 1C15 test stand that they were nitroglycerine with aluminum chloride (under arm deodorant) as a retarder. I do know of you found a piece and dropped it it would ignite

nope, morton thiokol – look up the challenger incident for everything you would ever want to know about composite propellant system design.

The Shuttle SRB propellant was about 70% AP, 16% aluminum, a trace of red iron oxide, 12% PBAN (polybutadiene acrylic acid acrylonitrile), and 2% epoxy curing agent (I think that was Dow’s DER332 but am not sure). If memory serves, the mixture was cured for over a week at about 120F. PBAN requires elevated temperatures for compolete cure. The newer binder, HTPB, can cure overnight at room temperature if the right curing agent is used.

Years ago I toured American Synthetic Rubber Company, who was the sole manufacturer of PBAN. My guide said it took about three months to make enough PBAN for the shuttle to burn in about three minutes. :-)

Ordering AP was easy enough like 10…15 yrs ago here in Germany (or the EU for that matter). All that stuff including potassium nitrate (all oxidizers tbh) are like super forbidden now. You could still get that stuff if you wanted, but it’s easier than ever getting on a watch list OR getting the stuff delivered directly by agents.

Pyrotechnics was so much fun back then, now it’s just asking fo trouble very quickly…

As of a couple years ago at least, AP was readily available in ordinary pyrotechnic quantities in the US. (But hypophosphites for copper deposition on PCBs without rare metals, no, because of the DEA’s War on Reductive Chemistry.)

It’s still available but the price has skyrocketed. When surplus AP was readily available it ran anywhere from $2-5/lb depending on quantity. I haven’t found it for less than $15/lb, and to be assured of top quality, you’ll pay about $25/lb.

This is super cool. Well done Kip!