If you’re still toiling away at your entry for the Gearing Up Challenge of the 2023 Hackaday Prize, don’t panic! No, you haven’t lost track of time — due to some technical difficulties we had to delay the final judging for the Assistive Tech Challenge that ended May 30th.

Today we’re pleased to announce that all the votes are in, and we’re ready to unveil the ten projects that our panel of judges felt best captured the spirit of this very important challenge. Each of these projects will take home $500 and move on to the final round of judging. There are few more noble pursuits than using your talents to help improve the lives of others, so although we could only pick ten finalists, we’d like to say a special thanks to everyone who entered this round.

Better Living Through Technology

For the Assistive Tech Challenge, we asked hackers to come up with ideas that could help those with disabilities live fuller and more independent lives. For those of us fortunate enough not to need any assistive technology in our day-to-day lives, it’s easy to imagine this means developing improved prosthetic limbs — but the reality is often considerably more mundane.

Consider the PionEar project from Jan Říha. Built around a low-power machine learning accelerator, this small battery powered device lights up to provide a visual indicator when it has identified the sound of a nearby siren. Placed on the dashboard of a car, it can help make sure deaf or hearing-impaired drivers are aware that an emergency vehicle is approaching so they can take appropriate action. Jan says he developed this device after talking to those in the hearing-impaired community and identifying this scenario as a problem that people were struggling with.

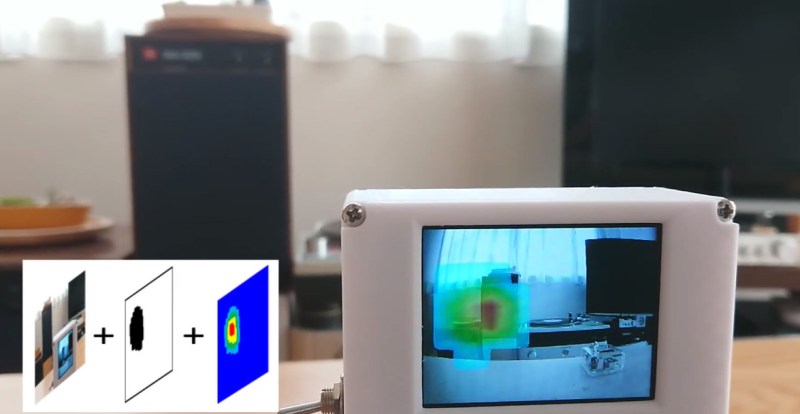

In a similar vein, the “Portable Sound Visualization AR Device” from AIRPOCKET uses an array of seven MEMS microphones on the front of the device to determine the direction that sounds are coming from. This data, when combined with a live video feed, can help the user identify the source of a sound that they might not otherwise be able to hear.

On the other hand, assistive tech doesn’t have to be limited to helping people with their daily activities. Indeed, it could be about enabling rare or even once-in-a-lifetime opportunities that might otherwise be impossible. Consider Mercator Origins from Mark B Jones, a dive computer designed from the ground up with inclusion in mind. This aquatic navigation system is intended to let blind or vision impaired individuals enjoy the freedom of movement and sense of weightlessness one experiences while diving underwater. Vibratory and audio alerts are used to help guide the diver between predetermined waypoints, while position and telemetry data is uploaded to a live dashboard so their process can be monitored from a distance — providing a feeling of independence while still maintaining safety.

Affordable Assistance

Instead of developing of new assistive technologies, other finalists focused their efforts on reducing the cost of what’s already available.

For example, BrailleRAP by Stephane is a DIY-friendly Braille “printer” that’s built from low-cost 3D printer components such as 8 mm rods, GT2 belts, and NEMA 17 stepper motors. The device, released under the CERN Open Hardware Licence v1.2, can be assembled for as little as $250 USD and is capable of embossing Braille text on standard paper, as well as thin sheets of metal or plastic. The desktop machine can therefore not only run off affordable educational or reading material wherever and whenever it might be needed, but can even be used to produce signage.

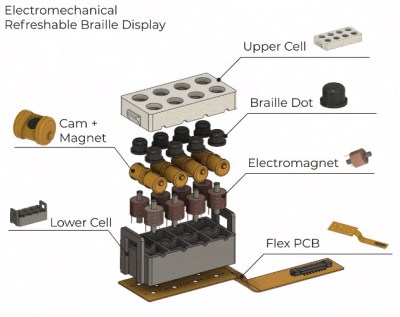

Similarly, the “Electromechanical Refreshable Braille Display” developed by Vijay seeks to smash the cost barrier that has kept Braille computer interfaces from becoming more widespread. By using an array of tiny electromagnets, each pin of the display can be raised and lowered independently with a minmum number of components.

Similarly, the “Electromechanical Refreshable Braille Display” developed by Vijay seeks to smash the cost barrier that has kept Braille computer interfaces from becoming more widespread. By using an array of tiny electromagnets, each pin of the display can be raised and lowered independently with a minmum number of components.

On the Hackaday.io page for this project, Vijay explains these displays can now be produced affordably by the hobbyist thanks to the increased commercial availability of 0.5 mm NdFeB magnets as well as high-resolution 3D printers.

In both cases, a technique which has been around since the 1800s has been made more accessible and affordable thanks to the ingenuity of passionate individuals using commodity off-the-shelf hardware. They serve as important reminders that the evolutionary progress of modern technology means even the most time-honored of concepts can benefit from the occasional rethinking.

Assistive Tech Finalists

- Powered Chair Smart Controller

- BrailleRAP: DIY Braille Embosser

- Helping H.A.N.D.S.

- Electromechanical Braille Display

- Speak To Me: A Button Box

- Mercator Origins: Sat Nav for Divers

- Portable Sound Visualization AR Device

- PionEar: Safer Roads for Deaf Drivers

- OHMni-Stick

- Pill Dispenser Robot

Going Green

The Assistive Tech Challenge might be over, but the 2023 Hackaday Prize continues on. An announcement about the finalists of the Green Hacks Challenge is right around the corner, and of course we’ve still got a couple weeks before the Gearing Up Challenge ends on August 8th. After that, it’s time for the Save the World Wildcard, where things can get really interesting.

Of course, none of this would be possible without our incredible sponsors. Special thanks to Supplyframe and DigiKey for making the Hackaday Prize a reality, and giving these incredible ideas a chance to flourish.

Congrats to everyone!

It’s a pity that two great projects were left out of the list:

https://hackaday.io/project/184945-affordable-bionic-prosthesis – a really good, open source prosthetic leg design. Something that is good enough for practical use – which means a huge lot more of effort invested comparing to proof of concept state of some listed projects.

https://hackaday.io/project/187922-open-muscle-finger-tracking-sensor – implementation of a novel approach to reading muscle signals with very decent recognition results. And while yes, it was tested only on author’s hand, no tests with people who don’t have their arms yet – but it’s a really important effort, a research that needs to be completed – it may or may not greatly improve prosthetic arms control, and only support from the community can drive this kind of research forward. I personally was sure this project will be supported at this stage.

All in all, a little more diversity of covered topics really wouldn’t hurt – some assistive topics got multiple entries supporting them (not all of which have a great quality btw), and some were omitted completely

The affordable-bionic-prosthesis is one of the nicest projects I’ve seen here. very well done and its frustrating to see it not on the list. I can’t think of a project on the list that is better in any way than this one.

I felt confused when starting to read this article and even more so when finishing: ” the Green Hacks Challenge is right around the corner, and of course we’ve still got a couple weeks before the Gearing Up Challenge ends on August 8th”. Not sure how the finalists can be announced when Gearing Up is still open?

Green Hacks ended on July 4th, so they will be the next wave of finalists announced. Gearing Up runs until August 8th, those winners will be announced a week or two after that. By that time, we’ll already be into the final Wildcard Challenge.

Several decades ago I saw an article about converting a dot matrix printer into a braille printer. The only hardware conversion required was putting something like a really wide rubber band over the roller. This holds the paper slightly closer to the print head and provide a soft strike surface allowing the pins to puncher the paper. Unfortunately these days it seems there isn’t many new dot matrix printers for sale for under $250.

Given that Braille Embossers can cost $1000s, it is great to see a lot cost alternative. Well done!

E.g the $8900 Gemini braille embosser: https://nelowvision.com/product/gemini-super-braille-embosser/

For Braille we use a bit heavier paper, so the machine must be a bit more robust. The embosser in my old school sounded like machine gun when printing because impact force had to be high. Manual Perkins braillers use cam mechanism to push the pin from below into the paper, above which there is brass plate with matching concave holes to form perfect points. Other type used lever action to move the pins up 1-2 mm up, but the corresponding key had more than 1cm of travel…

Regarding the first one, PionEar. Here in the Netherlands, there is an app called Flitsmeister. It’s usually used to display mobile and stationary speed camera’s (the original function), but nowadays has tons of features like parking information, road quality and, sirens. Sadly it only works for ambulances and firetrucks. Not police, for obvious reasons, but when one is headed in my direction, my phone starts making a loud noise (really annoying to hear at full volume inside my helmet) and it will show info about it on the screen in a bright orange color. It’s really neat because I’m aware of the ambulance/firetruck even when I can’t see or hear the vehicle coming. If I’m not mistaken it works in the entire EU these days. I do wish tech like PionEar was built into every new car.

Years ago, a group of black SUV’s (likely anti terrorism team or something like that) was driving very quickly on the highway with flashing blue lights and sirens on. This elderly person was driving on the passing lane and just wouldn’t move, driving the same speed as the person next to them, about 10 below the speed limit. There was no shoulder available there to let the SUV’s pass. After about 30 seconds or so with the SUV blasting sirens and flashing lights behind them, the SUV tapped the rear bumper of the car. Then he moved. This would have been perfect for someone like that. Although revoking the license might have been an even better option.