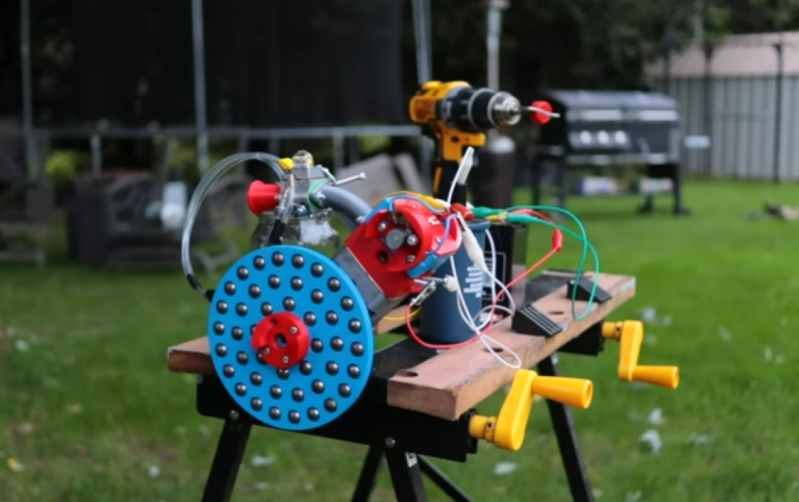

3D printed materials have come a long way in the last decade or so as printers have become more and more mainstream. Printers can use all kinds of different plastics with varying physical characteristics, and there are even printers now for other materials like concrete and metal. But even staying within the realm of the plastic printer can do a lot of jobs you might not expect. [Camden Bowen] recently 3D printed a single-piston engine which nearly worked, and is back with some improvements to it thanks to a small carburetor.

The carburetor itself isn’t 3D printed (although not from lack of trying) — it’s on loan from a weed eater, and is helping to solve a problem with the fuel-air mixture of his original design. Switching from butane to a liquid fuel also solved some problems as well, and using starter fluid also helped to kick off the ignition. Although it ran for a short period of time over several starts, the valve train suffered some damage with the exhaust valves melting in place to the head. This is actually a problem common to any internal combustion engine like this, especially if the fuel-air mixture is too lean, there’s incomplete combustion, the valves aren’t adjusted properly, or any number of other problems. In this case it seems to have been caused by improper engine timing.

It’s actually noteworthy though that the intake valves weren’t burned, meaning that if the engine can be tuned to allow for complete combustion before the exhaust gasses leave the combustion chamber, the plastic 3D printed head and valve train will likely survive much longer operational periods. We’ll certainly look forward to the next iteration of this engine build to see if that’s the case. If 3D printed piston engines aren’t your speed, though, take a look at this jet engine which uses a 3D printed compressor.

Thanks to [Rickert] for the tip!

Or, y’know, the exhaust valve melted because it’s made of plastic and being repeatedly exposed to 900 C gas exiting the cylinder. What’s the temperature of the 3D printer’s hotend?

It might survive longer if made thin and filled with water to sink heat, but without a way to circulate the water into and out of the body of the valve that’s only a temporary measure.

This. Even metal valves, particularly exhaust valves, depend on their intervals of contact with the cylinder head to cool them so they won’t be damaged by the heat. This in turn depends on them being made of a material that conducts heat well. Plastic don’t cut it.

Oh cool, I learned something new today. Thanks!

Some older high performance engines used sodium filled valve stems to draw heat from the valve to the stem for dissipation. Sodium melts at around 98°C, and can carry a good amount of heat via convection. Newer alloys have made these obsolete, though.

Well.. getting it to run for a brief time is still getting it to run. I imagine it’s still a thorough learning process and he will still have that knowledge and probably even the STLs if/when metal printing becomes more accessible.

This is for bragging rights only, kinda like welding tinfoil. He built an ICE out of corn.

I’m sure that’s part of the next version. Should already be impressive enough that he even got something like this to run.

Super cool!

Set the ignition timing earlier. And make the alcohol fuel mix real rich. Then it may run for three more seconds or so before melting…

The good thing is – if it runs as a plastic design for a few seconds it’s worth ordering printed metal parts from a pro manufacturer. Overall very cool project.

Super cool!

I’m just impressed that someone’s crazy enough to try to 3D print an engine

“The carburetor itself isn’t 3D printed (although not from lack of trying) — it’s on loan from a weed eater[…]”

I don’t recall it being 3D printed, but the Smarter Every Day YouTube channel demonstrated how a carburetor works by using one made from transparent plastic.

Leave it to armchair experts to tell someone why something can’t be done, while that person is off doing it anyways.

Leave it to armchair experts to misinterpret constructive criticism.

There are already several suggestions posted here that would support running for substantially longer before thermal failure. That’s far from “can’t be done”. It’s more in the vein of “if you stop overlooking some simple factors, success becomes easier and more complete”.