Hydrofoils have fascinated naval architects and marine designers for years. Fitted with underwater wings, these designs traverse the waters at great speed with a minimum of drag. As with many innovative technologies, though, the use of hydrofoils is riddled with challenges that often offset the vast benefits they offer.

While hydrofoils promise a better marine transportation experience, their adoption hasn’t been smooth sailing. In this article, we’ll dive deep into the potential and pitfalls of hydrofoil designs, and look at the unique niches this technology serves today.

Potential and Pitfalls

A hydrofoil craft is named after its primary feature—the hydrofoil — and it really is the water equivalent of an airfoil, tuned for operation in water instead of air. Where an airfoil generates lift for a plane, a hydrofoil beneath the water’s surface can generate lift for a boat.

The key advantage of hydrofoils is the reduction of hydrodynamic drag. As a hydrofoil-equipped vessel speeds up, the hydrofoils lift it above the water, essentially enabling it to “fly” over the surface. The concept should not be confused with hydroplanes, which use a specially designed hull to force water downwards, creating lift at high speeds.

When travelling at speed, the hydrofoils and their support structure remain in the water, along with some propulsion components. Because most of the boat is no longer in the water, hydrodynamic drag is massively reduced. In fluid mechanics, this is referred to as “reducing the wetted surface area,” which makes the concept particularly obvious when talking about watercraft. With drag from the water slashed, this allows hydrofoil craft to achieve significantly higher speeds than conventional hulled vessels.

The reduction in drag has other flow-on effects, too. Vessels equipped with hydrofoils can theoretically demonstrate better fuel efficiency. This not only translates to cost savings but can also contribute to reduced greenhouse gas emissions in marine transportation. However, it’s important to note that this can be offset by the fact that hydrofoil needs to operate at a certain minimum speed to lift out of the water. Below this speed, the foils do not generate enough lift to carry the vessel’s entire weight. At low speeds, or at a stop, a hydrofoil vessel floats lower in the water like conventional watercraft.

Furthermore, by lifting the hull above choppy waters, hydrofoils can offer a smoother ride, particularly in rough conditions. This feature is particularly beneficial for passenger-carrying designs, offering greater comfort for those onboard.

Types of Hydrofoils

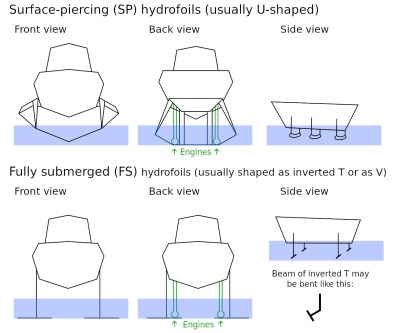

It bears noting that hydrofoil craft come in a variety of configurations, with designs primarily sorted into two categories—surface-piercing and fully-submerged designs.

Surface-piercing designs, with their U-shaped foils, have the benefit of inbuilt stability in pitch and roll. For example, if a surface-piercing hydrofoil pitches to the right, the greater submerged surface generates more lift, pushing the craft’s pitch back to the left. The same is true in pitch.

By contrast, fully-submerged hydrofoil designs have the foil itself always beneath the surface. These designs rely on automatic systems to actively control the hydrofoil’s angle of attack to maintain stability. As a bonus, though, with the foils fully submerged, these designs are the least affected by choppy conditions on the surface.

The technology does have its drawbacks, though. Hydrofoils demand intricate design and precision construction. This complexity can lead to higher production costs and also means that maintenance can be more demanding than conventional vessels. Weight must also be carefully managed—if a hydrofoil boat is overloaded, it won’t have enough lift to rise out of the water. Another headache for hydrofoils is cavitation. At higher speeds, cavities form in the low-pressure zone around the hydrofoil that then collapse, causing loss of lift and even damage. This frustrates efforts to build hydrofoil craft that can reliably travel beyond around 110 km/h (70 mph).

The hydrofoils themselves can also easily be damaged by striking debris, or they can become tangled in detritus. These designs also have much higher drag at low speeds, and can be difficult to operate in shallower areas due to the foils protruding to a greater depth beneath the surface. Ensuring stability, especially during turns and in varying sea conditions, can also be a challenge for hydrofoil craft. Hydrofoil designs need sophisticated control systems to maintain balance and prevent capsizing.

In The Real World

Hydrofoils are largely used in applications where speed is of the essence, and any potential drawbacks are of minimal consequence. Thus, they see great applications in racing sailing vessels and personal speedboats. They have also found application on “foil” surfboards, which allow a rider to deftly glide above the waves.

The commercial ferry industry has embraced hydrofoil designs for fast transportation, particularly on calmer lake routes. Voskhod hydrofoils were first designed in the Soviet Union, later built in Ukraine, and have been exported to countries around the world. Designed to operate in rivers and lakes, the boat carries up to 71 passengers can even operate in coastal sea areas for fast travel to islands. Other popular designs include the Boeing 929 (in the featured image) which operates widely across Hong Kong, Macau, Japan, and Korea, and the Kometa 120M which serves a variety of Russian routes.

With speed benefits on offer, military applications have also been found for hydrofoil technology. While the majority of navies stick with conventional craft, a decent number of hydrofoils have nonetheless been fielded over the years.

The US Navy fielded the Pegasus class, which operated from 1977 to 1993. Designed “Patrol Hydrofoil, Missile” or “PHM”, these craft were designated for the fast attack role, and armed with surface-to-surface missiles to take on enemy watercraft. The series was eventually retired for cost reasons, along with changing strategic needs as the need for fast patrols diminished once the Cold War ended. The Soviet Union similarly fielded a range of hydrofoil designs, including craft built for torpedo, missile, and patrol roles. Some of these craft remain in service today with the Ukraine and Russian navies.

Hydrofoil designs represent a compelling intersection of physics, engineering, and naval architecture. While they offer considerable benefits in terms of speed and efficiency, challenges persist, especially in broader adoption and integration into varied marine applications. However, as technology continues to advance and marine transportation seeks more sustainable and efficient solutions, hydrofoils might yet find their renaissance in the future seascape.

All the America’s cup sailboats are foil boats.

They can go much faster than the speed of the wind.

https://youtu.be/H98nH-dvNUE?si=mEO6pR9cCXJmL-FY

All the current America’s cup boats are foil boats.

All the current America’s foil boats are cups.

All the current cup’s America boats are foil

All the current cup’s America boats are

All the current foil cups are America’s boats

The recent rule change requiring traditional hull shapes with hydrofoils has made the Cup yachts hilarious to watch. They’re like the drag racer who brings a 1970s Toyota Corolla with a Wankel and leaves the line with the front wheels two feet off the ground.

The section title ‘TYPES OF HOVERCRAFT’ seems a little off, autocorrect I presume ?

I thought that too, but it could also be a play on words as a hydrofoil will “hover” over the water when running.

My hovercraft is named the ‘Full of Eels.’

Yeesh – fixed!

Similar to the roller ship.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roller_ship

Not similar, quite contrary.

Thank you for providing the link! I knew about the roller ship long ago, because my father has a set of bound copies of London’s “Strand Magazine” from 1891 to 1900. One of them has an article about the roller ship, but closes with the launching of the prototype. I had inferred that it didn’t revolutionise shipping, as no other ship of the kind was ever built, but the Wikipedia article finishes the story and explains why.

I remember it from an issue of Future magazine.

The sailing boat class ‘moth’ is nowadays centered arround hydrofoils. For me it is the class that was actually hacked: study the rules, find a corner, and do what everyone said it could not be done.

35 knots single handed is totally possible.

The more interesting discussion (and occasional rant) is how it took some upstart Kiwis and Aussies to throw off the shackles of “traditional” sailing with its prohibitive rule books and endless lawsuits (looking at you NYYC / America’s Cup) and actually start innovating past the 19th century. Pretty much everything came after that inspirational leap though it could be rightly argued that advanced materials and modeling made it inevitable somewhere. For the no-rules version, look up hydroplane surfing, kite or wave, and the electrically powered (“E-Foil”) versions that have followed from that.

Many people prefer sports with rules that equalise technology. Same for sailing as running shoes. Foils have recently become common in sailing due to materials and CAD/CNC becoming affordable and robust. But competitive foil sailing goes way back (e.g. Icarus speed sailing in ’70s), rules never held back popularity. Most recreational sailing boat choice is about cost, community, accessibility not “traditional”. Foiling moths are fun for some people. So are Toppers and Lasers, in spite of being obsolete technology. Ranting about sailing boat classes also remains popular.

the moth is a pain in the ass, the most complicated class of sailing and not the more fun. I prefer to wingfoil or kite foil for the fraction of the price of a moth and be more fun and faster.

Windsurfer and surfers routinely fly around on carbon fiber and aluminum hydrofoils, they are brilliant fun and easy to find second hand. Hard to make foil at home as precise shaping needed. But easy to attach to your own watercraft. Configuration: underwater “aeroplane” on vertical 800mm long ish fin. Amazing how people can balance.

You forgot one pro of the Hydrofoil, they look cool!

I actually rode that green ferry boat that is named Karla many times in my life because I used to live in that city where they didn’t even have a train station. All they had was a bus station and the connection was so bad it would, like most of the time, just not show up. And then this boat came into existence and it took you right up to the heart of Amsterdam and it was quick, it was very smooth, it was great.

There are also solar powered hydrofoil boats.

https://youtu.be/U6QFMshraVE?si=KAOvD8LAVbi7imos

There’s a hydrofoil beached near where I live, the Plainview. Very sad to me.

https://washingtonourhome.com/uss-plainview-the-ship-that-flew/