The blimp, the airship, the dirigible. Whatever you call them, you probably don’t find yourself thinking about them too often. They were an easy way to get airborne, predating the invention of the airplane by decades. And yet, they suffered—they were too slow, too cumbersome, and often too dangerous to compete once conventional planes hit the scene.

And yet! Here you are reading about airships once more, because some people aren’t giving up on this most hilarious manner of air travel. Yes, it’s 2024, and airship projects continue apace even in the face of the overwhelming superiority of the airplane.

Why Float?

As the world reckons with decarbonizing the economy, air travel has fallen under the crosshairs. As you might imagine, lofting gigantic metal tubes full of people into the air takes a great deal of energy. Aviation makes up a significant 2.4% of global carbon dioxide emissions. Work is underway to cut aircraft emissions through new efficiency measures and the use of biofuels, but demand for services continues to increase. Fiddling at the margins here isn’t going to solve the problem to any great degree.

Airships seem to offer some tantalizing bonuses to energy efficiency, however. With buoyancy provided by helium, airships don’t need forward propulsion to generate lift. Airplanes have to burn fuel to generate thrust to get enough speed up for the wings to work. All the while, the process of generating lift also generates drag, which costs fuel to overcome. In contrast, airships simply float upwards, essentially for free. The work of fighting gravity is done by the lifting gas in the airship’s bladders. Usually, it’s helium, because the Hindenburg disaster put most of us off ever riding in a hydrogen-filled airship.

Airships must still use fuel of some sort for propulsion to actually get to their destination. However, their minimum power requirements aren’t set by a need to maintain lift via wings. The airship will still float no matter how low the speed. Thus, where an airliner needs powerful engines just to get airborne, an airship can make do with less. This opens the prospect for electric airships, which could be a clean method of air travel if powered by renewable energy. Much research is ongoing in this area to determine whether such a method of transport could be feasible.

Slow Solar Airships

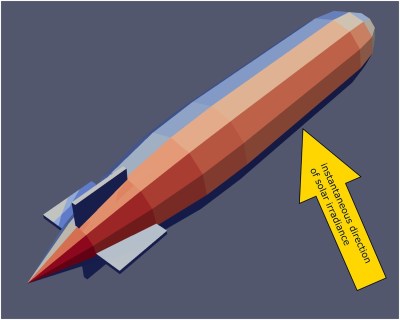

A paper published in the International Journal of Sustainable Energy recently explored the concept of an airship that uses onboard solar panels to harvest energy. Normally, we discount the idea of using solar panels on a vehicle for propulsion, as the surface area is too small to capture a meaningful amount of power. However, airships are huge, changing the calculations somewhat. The paper explored optimizing travel routes to enable the airship to fly between destinations using battery power and energy from the sun. It builds heavily on prior work, as many such papers do, but it’s rare to see one that references a publication from Zeppelin in 1908.

The paper based its theoretical airship design around using thin-film solar cells, which are light, flexible, and efficient all that the same time. The idea is that an airship’s skin would form an excellent surface with which to capture energy from the sun. Proposing a large airship design, it would see an area of over 13,000 square meters covered in cells, weighing in total around 6.6 tons. Such a craft would have to be carefully piloted to make the most of any available sunlight, both with regards to the timing of its journey and its angle to the sun. Done properly, though, the paper concluded that such a craft could achieve emissions just 1-5% of those of a conventional aircraft.

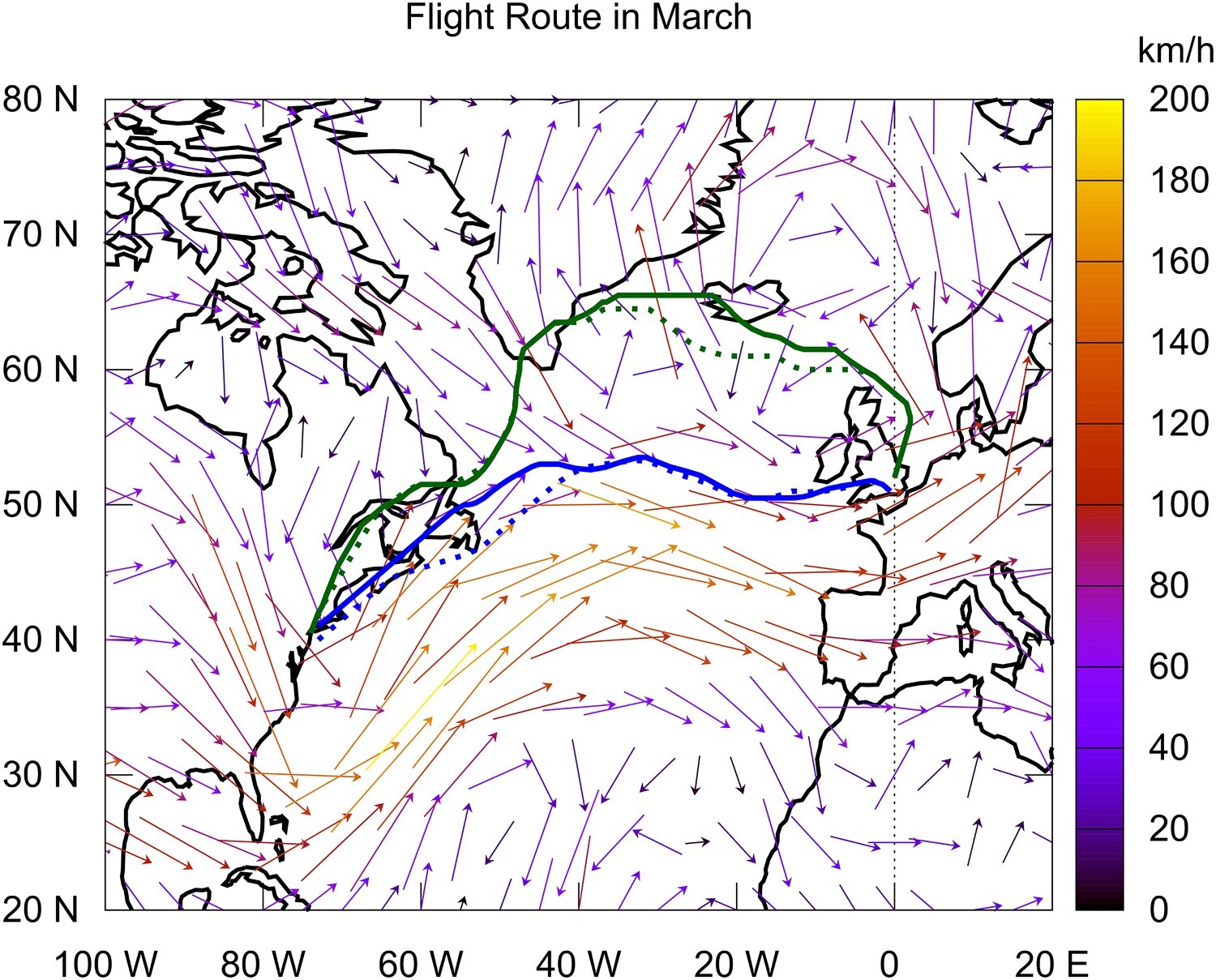

But what of practicality? The paper worked with a theoretical design capable of hauling 100 to 200 passengers on routes between Madrid and Las Palmas, and London and New York City. The journeys planned were roughly 1,760 km and 5,566 km respectively in their shortest, most direct routes. In the latter case, the journey would take 48 hours from New York to London, far longer than the usual 8 hour plane flight. Going back, the numbers are even worse, taking 76 hours on average thanks to typical prevailing winds and available sunlight.

Right away, it’s easy to see why we’re not blimping from city to city today. Or should we say airshipping, because blimps typically refer to smaller craft without rigid frames. No matter how cheap or efficient, few of us could afford the time to spend two or three days travelling by airship. Beyond the strain of such a journey, which would almost certainly necessitate sleeper cabins, you’d also need to take multiple entire seasons of TV to watch to get you through. You won’t get through Friends (around 88 hours) but you’d get through Seinfeld (around 69 hours) just fine, assuming you didn’t sleep between London and New York.

That’s not to say the technology is useless. The International Conference on Electric Airships took place to examine a number of potential uses for these cleaner forms of travel. Cargo doesn’t always have to move quickly, and could be a viable use for such airships. There are potential uses on some smaller passenger transport links, as well as uses for travelling to remote areas where conventional aircraft may be difficult to service. The conference also saw researchers sharing ideas on hybrid powertrain designs for clean airships, ultra-light solar solutions, and analyzing the economics of various use cases.

In any case, the well-documented flaws with airship travel aren’t stopping development in this space. Catching the headlines of late is the Pathfinder 1, a 400-foot airship built by LTA Research. That makes it almost twice as long as a Boeing 747-8, or roughly half as long as the largest Hindenberg-class Zeppelins. The company has been granted a special airworthiness certificate for the large aircraft, with testing to take place throughout 2024. It has a skeleton made of titanium and carbon fiber, supporting 13 bladders filled with helium to provide lift. Unlike some other modern airships, it’s not a hybrid lifting body design, and actually looks not that far removed from the airships of the 1930s, dangling gondola and all. The aim is for the airship to support disaster relief efforts in areas where conventional aircraft infrastructure may be damaged. It will also explore the use of hydrogen fuel-cells for cleaner power, though it is currently built to rely on diesel generators to run its electric motors.

Ultimately, airships aren’t going to replace planes any time soon. They’re simply too slow to get the job done. At the same time, they seem to keep popping up in niche uses here and there. And true, it could be that one day, air cargo is supported by large helium airships running on solar power for cleaner haulage. But for now, it seems like the basic fundamentals of airships will keep them as a neat obscurity, rather than a key technology underpinning global trade.

Oh, this is easy – no. No they can not.

First and best. No need to read farther

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Betteridge%27s_law_of_headlines

I’m going to need to remember that….

Perhaps someone might study a little history, there are REASONS that airships fell out of favor and will every time it is tried again.

“In any case, the well-documented flaws with airship travel aren’t stopping development in this space. ”

No plugs to fall off.

“Ultimately, airships aren’t going to replace planes any time soon. They’re simply too slow to get the job done. ”

Think cruise ship, not plane.

Is there not the second main problem after fuel (Helium, hydrogen or hot air), that airships have to be somewhere near seelevel? Thats why all constructionshalls are next to water.

I think in case of rise of regulations, fuel reduction, cost cutting and carbon emissions this old concept fits more into this modern world.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caspian_Sea_Monster

This would depend on the level of pressure differential the gas containers could handle and the reserve bouyancy – less dense air up high means less effective lift from a given volume of lifting gas.

But yes, they do have to fly much lower – and thus will be *heavily* affected by weather*. However, they’ve made Atlantic crossings reliably so its, IMO, a pretty solved problem.

——

The CSM only works at crazy low altitudes though. Not really safe over land. Or comfortable if you’re flying NAP over hilly terrain;)

I love the Caspian Sea Monster but it really was a product of the cold war. It’s niche is super fast heavy lift. Faster than a carrier, more lift than typical planes, can drop a handful of tanks/vehicles at a moment’s notice. But commercially there’s little niche for overnight vehicle deliveries across the ocean, most people can wait for the slow boat on heavy objects.

“Faster than a carrier, more lift than typical planes, can drop a handful of tanks/vehicles at a moment’s notice.”

Most importantly: Only where the ground is flat or the water has no waves – and nobody is shooting at you.

If it has a cabin, i would love to used it for over night flights to bali.

Not at all. During the First World War German zeppelins reached altitudes of 20,000 feet and that was with leather bags for the hydrogen and an aluminum alloy structure. With modern materials they should be able to cruise much higher.

Nobody goes on a cruise ship to get over the sea – they’ve become floating amusement parks, and the point of going on a cruise is to float around in a pool drinking yourself senseless, go to theaters, shop in the tax free…

None of that is possible on an airship. It’s more like crossing the continent on a train: tiny sleeper cabin and expensive food in a tiny restaurant car, reading books and looking out of the window for a couple days until you’re there. Needless to say, almost nobody takes the train when they can fly.

Much better than crossing the continent on a train. It’s faster and more luxurious. Here are some photos of the accommodations on the R101 for example. https://www.airshipsonline.com/airships/interior/R101Interior.htm

Still an order of magnitude worse than taking a plane or driving though.

I’ve never been in a car, bus, or airplane where I could sit down to a gourmet meal made from scratch in a chair in an elegant dining room. Nor have I ever been in an airplane where I was free to walk around and had a multiplicity of places to sit while enjoying the view or conversing with other passengers.

Thing is, those interiors were still made for rich people who could afford it. To make economic sense for the wider audience, they’d have to pack in more passengers which would mean train-like conditions.

However, what airships do have is space. You could climb up and down and walk the walkways under the gas bladders. You just can’t have anything in those spaces that would add mass, so you can’t have e.g. a casino on board. What you get is deck chairs and books.

so dumbbells or a pool is out of the question. But monkey bars probably are within the weight allowance :)

yeah not as fun as a cruise ship. My BFs went on a cruise that a swimming pool and gokarts. Gokarts on the freaking ocean.

Even a 50 year old commuter train (Amtrak) can be pretty nice compared to an airplane. Comfortable seats, large windows, wifi, electrical outlets, water, better restroom, etc. Quieter too. I guess if you spread out some simple rooms throughout the space, you could have isolation even if not a lot of heavy things, which is even better than a train. Probably much smoother, too. I could imagine it would be easier to pull out a laptop and some papers in such a place than on the other options. It made me think that businesspeople may be convinced to have online meetings in such an environment, instead of being somewhat hard to reach for the duration of a flight. I wouldn’t like to work on a flight, unless that let me extend my vacation by not needing to include travel time.

But unlike a train you can fly anywhere you want.

Provided the winds are going your way. Airships have to take circuitous routes much like sailing ships used to.

Yeah but you need an airport or at least an airstrip to land and get off of the airplane.

Glass Bottomed Cabins

Give me a bed on the flor and a full moon night and I be in.

But only if it was a no phones or other iluminated devices room.

The QM2 still makes Cunard a reasonable profit as an ocean liner. 8 nights transatlantic. If you could comparable luxury for three nights, I see profit there.

A cruise ship for the ultra rich if you consider the cargo capacity.

To provide the amenities and luxuries of a cruise ship, the thing would have to be massive. A 250 passenger cruise ship might be 20,000 tons, if hydrogen provides lift of 1.2031 kg per cubic meter. So, you would probably need about 20 million cubic meters of balloon, which is a over 500m long if you have a 250m width/height. That’s more than double the length of the Hindenburg (and much wider).

If you want to make it comparable to the Disney/carnival/princess cruise ship, it’s probably going to be much larger still.

Strangely, most people don’t want kilometer long airships flying over their houses, so, you’re likely to have legal issues if you try to fly it somewhere heavily populated.

“Strangely, most people don’t want kilometer long airships flying over their houses, so, you’re likely to have legal issues if you try to fly it somewhere heavily populated.”

No one tells aliens what to do.

Cruise ship with hardly any amenities. Take a look at the spartan conditions on commercial airships – even flagship designs like Hindenburg.

Not in the sense of comparing to air travel today. No one would except it except for a few environmental types that have nothing better to do :) .

But as a cruise ship so to speak, they may have some usefulness. Take a slow vacation cruise in the sky? Maybe?

“environmental types” because who needs an environment anyway right?

Are we there yet?

Wind alone say this concept will “never fly”. Wind is highly variable, not “typical”.

It is near the surface, in other layers of the atmosphere it is very predictable and can be ridden. Jetstreams are a thing.

The trouble is, the jet streams only really go one way east or west, so you have to travel significant distances across the streams north or south to catch the stream back.

You have to make really long trips, from New York to London, and then London to North Africa, then the other way to Brazil, then up to New York to get home, and half the way you’re not being helped by the streams so you’re on the engines fighting the local weather to stay on course.

When the Hindenburg crossed the Atlantic, it went from Frankfurt to Rio de Janeiro following the westerlies. It was several days faster than steam ships on that route, but directly from Germany to New York it would be slower.

Airships can’t really do jetstream heights though.

As you go up, the pressure outside drops, this causes your bags to expand – at some point they’ll rip or you’re spending a lot of precious weight to reinforce them.

And the lower the exterior pressure, the less bouyancy you’ll get from your lifting gas as that comes from the difference in density between the outside air and the lifting gas.

Or, y’know, you can pump from the bags into tanks. It’s a mass problem, sure; figure whether it’s lighter to use composite tanks at many hundreds of times the pressure of the atmosphere, or to reinforce your gas bags. But it’s been done.

That doesn’t make sense at all. Jetstreams aren’t all THAT consistent, they aren’t consistent as the year progresses (check out Ventusky month by month), and unless they make airports 40,000 feet high the dirigible still has to climb and descend through highly variable weather.

The Hindenburg did go around the world, as did several other airships. It almost crashed into mountains and was stranded several times due to storms, but they managed it.

With today’s safety standards, you just wouldn’t pull off a stunt like that.

“No matter how cheap or efficient, few of us could afford the time to spend two or three days travelling by airship. ”

Airships have plenty of other issues, but this doesn’t seem like the worst problem to me. It’s more a problem with our expectations and how much time (off) we have (or allow ourselves to have) then a problem with airships as such. After all, two or three days is still a couple days faster than what people used to happily cope with during the “golden age” of transatlantic ocean liners.

IMO, a lot would depend on how comfortable the accommodation was. I for one would be perfectly happy to arrive rested and comfortable, after spending a couple of days in a comfortable lounge watching the ocean and stars go by (and sleeping in a real bed), over the usual experience of being jammed into an airplane for 8 hours.

Experiencing the passage of time for two days certainly isn’t an insolvable problem. I myself have managed to do that fully seven times in just the last fortnight!

As for what to do, one would assume a modern airship would be well-connected via Starlink or the like. Anybody who does remote work could probably just do that. (Which would also neatly solve the “need 5 extra vacation days” problem, assuming your employment situation is amenable.) Failing that, books are still a thing. Or one could take up a new hobby – they probably sell little water color kits at the airfield. Or just study up on restaurant reviews at your destination.

“Cope” is the word. It’s still not a comfortable ride, and it’s liable to be very boring.

If you’re just going to be watching netflix for three days and staring out of the window, why leave home?

Because, you know, the world isn’t limited to your bedroom. There are plenty of things to see (and since such ship don’t climb at absurd height, you can see the land underneath) that are a lot more interesting than a n-th american movie where a super hero beats a super communist or a wealthy mad man that will spend all his money to destroy the world that made him rich.

I’d rather spend 2 hours on a hot air balloon at a location and get on with enjoying things on the ground for the remaining 2 days than spend 3 days floating slowly over mostly boring land. When you fly regularly as I do, time in the aircraft is just wasted life and discomfort. I’d much rather spend the extra 2 hours with my family in front of the TV or cooking a nice meal. I often used to take 8 hour ferry trips, I’m due one quite soon. They’re comfy and spacious, quiet and the hum of the engines and the bobbing of the sea is relaxing. But my god, I’d rather be almost anywhere else instead of trapped on a boat.

To me this concept is really just a novelty for short trips, not actual travel.

In a pinch they can just drop anchor and let the wind spin the props to recharge the batteries.

Anchors work by the weight of the chain, not the anchor itself. So you’re carrying several extra tons – and you don’t have a lot of margin here as we’re talking about being able to lift 1.1 grams of structure/payload for every liter of helium in your envelope.

It’s not literally like a boat anchor. It’s a mooring rope you tie down to something.

No they don’t, that’s an internet myth that seems to have appeared. At least not in 99% of cases. The weight of the chain is used to pull the flukes toward the ground with the lateral pull enabling it to bury itself, and the chain providing some spring in the rope to cope with swell.

If only the chain weight mattered, there would be no point in having elaborate fluked anchors at the tip. Chain and anchor weight are only considered alone in locations with poor holding ground, and that doesn’t work in high seas or winds.

FWIW there are literally hundreds of thousands of boats around the world which use a 3m length of chain attached to a 5kg anchor to hold a 2000+ Kg boat.

A beautiful concept that Lieven Standart pursues since a couple of years now: https://solar.lowtechmagazine.com/2009/02/camping-in-the-clouds-the-aeromodeller-ii/

The market for them isnt passengers. The best use would be air freight. Sure its slower than current air freight, but has the potential to move large amounts at a much lower cost than air freight while also being significantly faster than sea freight.

It can only move larger amounts if its ginormous.

1.1 g of payload/structure per liter of helium.

747 has a payload of, say, 100,000 kilos – that’s 91 million liters of lifting gas volume. 91,000 cubic meters. Roughly 150 m long by 40ish meters diameter. That’s just to lift the payload. Lets say 1/4 of that is structure – that’s another 23k m3. That’s a lot of drag. That’s a lot of ‘sail area’ to be pushed around by the wind.

Granted – its also a lot of surface area to be covered in solar panels.

It really is, like the article points out, only suitable for niche applications to get medium cargo loads into areas deep in places where its not cost effective to build a road (or ‘ecologically sensitive’ so you’re not going to get permission to build that road).

>air travel has fallen under the crosshairs

It’s an easy target for the kind of people people who like to talk about “late stage capitalism”.

There are much bigger and more important targets, but if you attack residential energy use (30% of CO2), or cars and transportation in general (another 30%), or industry (30%) or agriculture (10%), you’re going to make a lot of regular folks angry and they’ll tell you to shut up – so all the career politicians and eco warriors pick on targets that the regular folks don’t mind. They target these 1-2% sources and make a lot of noise about them, to distract from the fact that they can’t really do anything and don’t want to do anything about the elephant in the room.

Not sure where your numbers come from, but since they’re implausible and add up to >100% I figured I’d check for you:

Residential: 10.9%

Transportation: 16.2%

Industrial: 29.4% (solid guess!)

With 73% of CO2 coming from fossil fuel use, targeting *all* those sources seems like the smartest idea. That’s why there’s a push for green energy, and electric cars, and…. You can break any of the sectors down to <1% chunks, does that mean none of them should be worked on? Nobody is only trying to reduce emissions for air travel thinking it will solve the entire problem, but every little bit helps and the sooner, the better.

https://ourworldindata.org/images/published/Emissions-by-sector-%E2%80%93-pie-charts_1302.webp

Sure. Except we’re not interested in sitting in a cold, dark, pod, eating the bugs, not owning anything, and taking the train to our shift at the Amazon-Walmart Fullfillment Center #25422

That’s all greenhouse gas emissions, which are counted as CO2 equivalents. For example, chopping down a forest is counted as an emission. My numbers come from the US department of energy, accounting for direct CO2 emissions per economic sector. It’s rounded up to the nearest ten percents.

>and add up to >100%

No it doesn’t. 30 + 30 + 30 + 10 = 100. The smaller sources are included in those sectors.

>You can break any of the sectors down to <1% chunks, does that mean none of them should be worked on?

There are root problems and then there are "branch" problems. Liquid fuels as an energy carrier is a root problem that solves many of these 1% issues if it can be helped, with e.g. synthetic fuels. It makes no sense to go after the effects of the fundamental problem than the cause itself. Just like trying to save money to save yourself out of a debt doesn't work because the money you borrowed will never pay the interest. What you really need to do is earn more money.

Um, what? Trying to invest money to get out of debt, sure – you’d be unlikely to be on the right side of the interest equations in the majority of cases. But you can definitely try to save money by just spending less of it, rather than requiring more and more growth.

Same with fuel usage; the 5-15% of my fuel that’s made of renewable ethanol isn’t a bad thing, though it isn’t as energy dense as the other components. If I had the fuel production of Brazil with their sugarcane, that could be fine. However, the biggest determinant of how much fossil fuel I use on a given day is whether I must commute to work and where I need to go. Or for winter heat – I might be able to save some heating emissions if my heater was more efficient, but I’d save a lot more if I had better insulation and/or I could use a lower temperature while still keeping my pipes safe. Or for the industry required to provide me with products – I can maybe have a small effect by choosing between equivalent products based on the efficiency of their factory, but I can save a lot more by avoiding the need to buy a new product at all. Even if I do need a product, I may not need a brand new one to be produced for me.

You do know that the vast majority of helium comes out of natural gas wells right? Not so green after all.

Better to harvest the helium than just waste it.

For travel? Eh, people might go on one for a lark but too many wouldn’t like to be isolated for long enough to cross great distances, given the assumption you can’t do as much as a cruise ship could. But if you could scale up and carry things that are too dimensionally large for roads, rail, or any affordable cargo plane, while only needing a suitably equipped tether location, maybe you’ve got something. And of course, if the thing has indefinite range, then if the only manufacturer of some delicate subassembly is in Italy but everything else is produced on the other side of the world, maybe it could go direct from one to the other.

I suppose you could use one as a venue. Some dedicated hotshot businesspeople could get small private rooms on them so they don’t even have to stop having meetings while flying from A to B. There’s already a bit of that with in-flight internet access.

The biggest problem faced by large airships is the wind. The small ratio of power to surface area makes them very sensitive to winds. Nearly all crashes were due to winds. The closer to the surface the more unpredictable the winds are. One of the best ideas I’ve seen is not to land the airships but keep them at altitude and to ferry the passengers on and off using airplanes.

That becomes more doable with the advent of EVTOLs.

Solar Freakin Airways!

Also, I’m not a fan of venting helium to atmosphere. Wasting resources to save the environment seems a bit backwards.

Why would there be a need to vent Helium to the atmosphere?

How we do things now is fine, we will just use some form of nuclear power to produce very clean burning synthetic fuel, because that is sustainable in the long term, and has nothing to do with the nonsense about climate and CO2. Same with many types of ground vehicles and shipping, except the large ones that can go nuclear. The real issue with transport is particulate matter and the question of if that is good, bad or neutral varies with context. Breathing it in because you live in an urban environment is clearly not good. Fuel cells that consume synthetic hydrocarbons may be the most pragmatic solution in some cases. Pretending that CO2 “bad” is insane, therefore a more mature, context sensitive, and nuanced view of the topic is required.

Wasn’t helium a rare gas with no renewable source?

Absolutely. And it escapes to upper atmosphere so there no “let’s mine our old landfills and crap”. Moreover there is no path to practically manfacture it.

You absolutely can revert CO2 and water all the way to diesel or even longer hydrocarbons using just electricity as overall input. But only way to create helium is fusion. And it is required in medicine and science… eg. in MRI machines etc..

Yes, it is a rare gas that is not renewable. But the thing is in certain places it just leaks or is released out of the ground. This will happen anyway. So we either use it or we’ll loose it.

Just use hydrogen, and generate it from air humidity or rainwater while you’re in the air. Hydrogen ships can be made safely, and were safe in the past as well. According to the pilot’s own testimony, the Hindenburg was sabotaged by an incendiary round shot at it. With modern engineering, hydrogen airships could be made to survive even those circumstances.

^^^ This… “oh, the humanity” notwithstanding. We launch rockets filled with millions of gallons of explosive liquids, eh? Frankly, hydrogen gas, managed in some form, is the only solution (I submit).

The “sabotage” hypothesis was never confirmed. Far more likely is that there was a hydrogen leak. Static electricity discharge ignited the hydrogen.

The Hindenburg had some trouble coming in – there was some difficulty in keeping the ship level, presumably due a leak in one of the lifting cells.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindenburg_disaster

Yet German airships flew many missions in The Great War without this being a problem unless they were damaged by the enemy.

No. Its not ‘renewable’ (except through nuclear reactors) but its not rare. Its pretty common to get it from fossil fuel extraction (where basically it all comes from) and we used to have a strategic reserve until the government decided to start selling it off for some reason.

Has any company designed ones to deliver wind turbine parts?

Since turbines keep getting bigger and bigger, it’s harder to transport them, which might make it viable in that nitch market, though, there is no reason it has to be solar or even electric at that point.

I wonder if an stationary solar powered airship could generate power and send it to the ground.

There have been past designs of a tube shaped airship with a turbine in the middle to generate power more effectively along with be easily deployable in disaster areas.

Why bother, the amount of atmosphere between the airship and the ground is insignificant compared to the atmosphere above it. The increase in solar radiation would not be worth it. That and you have to factor in the production of helium and the energy that takes.

There is a plan to explore Venus by flying a blimps or have a floating city in the high atmosphere where winds, temperatures, and pressure are in acceptable limits.

https://www.cnn.com/2014/12/23/tech/innovation/tomorrow-transformed-venus-blimp-city/index.html

So many problems with it. Are they worth overcoming? In the history of airships, there is one main problem. Speed. If you can not go faster than the fastest winds you might encounter, you will get pushed into things like mountains or places you don’t want to go, like Antarctica. And there is the icing. Two man things. Speed and icing. Picking up snow and ice proved the end of a number of the big airships. I think the big Airship hanger at Moffett Field/Google was for the Navy airship Macon and it sank off the California coast from icing. You must be able to prevent icing on a very large surface. Then there is maneuvering and landing in gusty conditions. Three main things. Speed, Icing, and landing! And there is lifting abili…Four main things. Hydrogen can go a long way to remedy that and reduce the size. A given volume of H2 is half the weight of He.

Unruly passengers could be given a small cabin that is lowered on a cable until they are out of hearing. (In WWI, German Zeps were used for night bombing England and had such a rig to lower an observer through the clouds and direct the ship towards a target.)

There is one possibility with good economics and very low carbon footprints compared to alternatives. Very large ships could be used to transport natural gas by using it as the lifting gas. However, given the reality of today’s happy terrorist and all the fun drones and missiles supplied by the Axis of A-Holes to attack shipping and whoever strikes their fancy, one might think airships are just too attractive a target. I would shelve the whole idea for the time being.

Hydrogen Laputa, Jonathan Swift. Hyputa. And what about shadow of such hyperairships. But astronomers can have observatories on the top of Hyputas.

Not solar powered, but still an airship.

https://oceanskycruises.com/north-pole-expedition/

They’re taking bookings for 2026, if you have $200k to burn to rent a cabin for 48hrs.

I don’t have $200k to burn, but that does look pretty sweet.

Cargolifter, here we go again.

https://de-m-wikipedia-org.translate.goog/wiki/Cargolifter_AG?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=de&_x_tr_pto=wapp

Cargolifter Wikipedia in English:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CargoLifter

Why “fill it” with anything at all? A vacuum is not flammable, and can lift more weight per unit volume than H2.

Calculate the atmospheric pressure acting on the hull and then tell me how to withstand it with a structure lightweight enough to still fly…

That calculation was done 400 years ago using 0 ATM and the prevailing materials of the time composed of iron.

.7 ATM with carbon fiber frame composite has been patented

Anuma Airspace is starting with permanent weather balloons in the next few years: https://www.everybodyinthepool.com/episodes/episode/8f8507d2/episode-22-floating-airships-of-the-past-and-future

It’s not a problem if you’re at the top of the atmosphere. Use a plane, dock, fry around the world, drop them back to earth.

I just got done watching Kiki’s Delivery Service again and thinking about that scene with the zeppelin….. Yeah, I’m good. Tell how the trip goes.

There’s an XKCD that observes that when someone says their invention might be useful in disaster aid, it’s usually because they can’t think of an actual commercial application. Or something to that effect. I wager that the situations in which you can wait two days for an airship, but not five days for an actual ship are pretty limited. On land, road or rail.

As the world reckons with decarbonizing the economy, air travel has fallen under the crosshairs. As you might imagine, lofting gigantic metal tubes full of people into the air takes a great deal of energy. Aviation makes up a significant 2.4% of global carbon dioxide emissions.

——–

And how much of that 2.4% is from private jets and planes? Methinks a lot. I am more concerned with the carbon footprint of someone jetting around the world in their private jet, landing, taking a gas guzzling suv to a meeting with other likeminded people who try to tell us the majority are to blame, before vacationing in a huge yacht and laughing at how gullible most of us are. There are people who live in mansions and live lifestyles that harm the life more than a million people combined. Stop passing on the blame.

People have been trying to build airships for many decades. It seems easy until you start looking at the construction and design issues and how it impacts performance. I believe the problem is that most designs are way off scale.

Many years ago, Buckminster Fuller began playing around with the notion of a very large Aerostat. If you build it large enough, pretty soon the problem is not how to get it in the air, but how to keep it within reasonable distance from the ground. Nevertheless, it has to be insanely large. He was thinking about building entire habitats in spheres.

Perhaps this design problem is one of getting the scale of operation right. In any case, many smart people have stubbed their toes on this problem. It seems deceptively easy, until you try building and operating one.

Maybe we should just make an inflatable aerofoil.

An airship with jet/propeller engines for propulsion that is not just made of a helium balloon for lift, but also gets more lift from it’s shape.

Personally I’m hoping to see a vacuum airship one day. Maybe carbon nanotube infused artificial spider silk or similar.

I’ve read comments like “no, you can’t power an airship with solar energy” or “airships will never replace airplanes”, as if the goal of aerospace research in vehicles powered by lighter-than-air gases combined with The use of renewable energy aimed to create hypersonic vehicles for passenger transport.

Guys, we’re talking about keeping heavy things in the air for a long time at reasonable costs here. Can airships be powered by solar energy alone? Nobody believes this. Because airships have never relied on just one type of energy to keep them aloft: lift, mass, gravity itself, wind and the different temperatures of the air currents it passes through… there’s a lot of stuff. Until now we have powered airships with diesel and non-electric engines powered by solar panels only because the latter were poorly performing and heavy. Over the last twelve years, solar panels have more than doubled their power and solutions such as thin film have made this technology useful for this purpose. Not alone obviously: air is a fundamental component for lift and for changing the structure with a minimum use of energy. The tensions operating in the structure of the airship are also a non-negligible source of energy production.

As for the transport of people, airships are not designed to compete with passenger flights over medium and long distances, but with buses and trains over short distances and above all with measurement and control instruments and with heavy transport vehicles.