Every time there’s a plane crash or other aviation safety incident, we often hear talk of the famous “black box”. Of course, anyone these days will tell you that they’re not black, but orange, for visibility’s sake. Plus, there’s often not one black box, but two! There’s a Flight Data Recorder (FDR), charged with recording aircraft telemetry, and a Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR), designed to record what’s going on in the cabin.

It sounds straightforward enough, but the cockpit voice recorder has actually become the subject of some controversy in recent times. Let’s talk about the basics of these important safety devices, and why they’re the subject of some debate at the present time.

That’s a Hot Mic

When it comes to figuring out what happened in an air disaster, context is everything. Flight data recorders can tell investigators all about what the plane’s various systems are doing, while more advanced maintenance recorders developed by airline manufacturers can deliver even more granular data. Knowing the control inputs from the pilots, the positions of control surfaces, and system statuses is all relevant to piecing together what happened. However, there’s also a lot that can be learned from the pilots themselves. Past research has found pilot error to be a factor in over a third of major airline crashes. Knowing what pilots are thinking at a given moment isn’t quite possible, but having a recording of their conversation can provide good insight. The cockpit voice recorder plays a pivotal role in this regard. It’s also useful for capturing other sounds, too, like rattles, thuds, explosions, or alarms going off in the cockpit.

This information can prove crucial in the event of an incident or accident. It aids investigators who must try and piece together a sequence of events and contributing factors. An instructional example is the case of Air France Flight 447. Flight data indicated that the plane was likely subject to icing on the pitot tubes, leading to unreliable airspeed measurements. The crew’s response was incorrect for the given situation, with the voice recording clearly laying out how the errors made led to the tragic loss of the aircraft and the lives of all on board. Without the voice recording, there would have been a far greater mystery around how the plane came to enter its deadly stall before plummeting into the water.

So, cockpit voice recorders are super useful. With today’s modern storage technologies, we must be recording and storing what goes on in every flight, right? No? Well… surely we’re recording for the full length of every flight, at least. Again, not quite.

As it stands today, there are notable differences in regulations around the world regarding the length of recording time required for a CVR. Once upon a time, recording durations were as short as 30 minutes, but this was often found to be insufficient to gain a good understanding of a safety-related incident. Today, in the U.S., the Federal Aviation Administration mandates that planes fitted with cockpit voice recorders have a recording duration for a minimum of two hours. Recording is done on a loop, such that as the recording continues, older audio is overwritten, preserving just the last two hours of sound recorded from the cabin.

Obviously, modern technology has made storage incredibly cheap. While early units often used magnetic recording on wire or tape, more recent designs have relied on solid state digital recordings. There’s no real technical reason for CVRs to only record two hours of audio, but airlines and aircraft manufacturers build to the regulation. There’s also great expense required to get a new piece of equipment designed and approved for safety-critical use in an aircraft. Without a regulation mandating longer recording times, US airlines have little reason to invest in upgrades to their fleets.

In Europe, however, there’s a rather different picture. Under the regulations set by the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), aircraft with a maximum takeoff weight exceeding 59,500 pounds must have cockpit voice recorders that store at least 25 hours of audio. This regulation applies to aircraft manufactured after Jan 1, 2021, and doesn’t explicitly require that earlier aircraft be retrofitted.

The European move has led to calls for the FAA to adopt similar minimum standards. Most recently, the chair of the National Transport Safety Board has called for the 25-hour recording period to apply not just to newly built aircraft, but existing planes as well. This was in part due to the case of Alaska Airlines Flight 1282, in which a Boeing 737 MAX 9 had a door plug blow out at altitude. Unfortunately, after the plane landed safely, neither the crew nor other technicians switched off the breaker for the cockpit voice recorder. Thus, it kept recording while on the ground, and overwrote the relevant period in short order. A 25-hour recording would have provided a much longer period for somebody to realize and shut off the CVR, even if it’s an imperfect solution. The 25-hour limit is also of use to provide full coverage of longer international flights. The FAA continues to accept comment on the matter until February 2, 2024.

Privacy in the Cockpit

There are other limits on cockpit voice recorders, too. Privacy has been a major concern for pilots and aviation unions over the years, primarily regarding the potential misuse of recordings. While many of us are recorded by surveillance cameras on a daily basis in our places of work, they seldom capture the intimate details of conversations between colleagues. Pilots, on the other hand, have every word they speak recorded by multiple microphones in the cabin. On long flights, pilots will typically have all sorts of personal conversations, just like anyone else at work. There’s naturally some apprehension about having one’s conversations stored, and possibly listened to, in such a manner.

By and large, recordings from cockpit voice recorders are not released publicly, even in the event of a major crash investigation. Instead, when the NTSB investigates an incident, it forms a committee to listen to a recording. This committee usually consists representatives from the NTSB and FAA, the aircraft manufacturer, and members of the pilots union. The committee then produces a transcript for further use in the investigation and public distribution, where necessary.

While transparency can aid public understanding and trust in aviation safety processes, there are concerns about sensationalism and misinterpretation of the technical conversations by the general public. These matters are treated with the highest sensitivity; Congress mandates that CVR audio is not released to the public, in whole or in part. Even the written transcript can only be released on a set timetable, typically at a public hearing or when a report is issued for public consumption.

While there are strict rules in place, pilot unions and individuals have come out against CVR reforms on the table in the US. Prime concerns remain around privacy, and fears that airlines might begin to use cockpit recordings to pursue disciplinary actions or surveil pilots, rather than sticking to using the systems for safety investigations. Others contend that, in some cases, pilots have even worked around existing 2-hour recording limits to cover their tracks in cases of potential misconduct.

Ultimately, controversy continues to hold back cockpit voice recorders from being as good as they possibly could be. It’s likely that crash investigators in future will have to make do with what they can get as opposition to more capable recorders remains potent in the US. Meanwhile, European regulators seem happy to charge ahead and enforce a greater standard. We may yet learn from this folly, but hopefully not through the loss of some critical information that could solve a future airline tragedy.

I’m all for it.

Every now and then I watch a bunch of video’s from Mentour Pilot and it happens far to often that data from the CVR is not available after an accident.

And for me, the responsibility for a few hundred passengers and the plane itself far outweighs the privacy concerns of whatever a pilot chooses to talk about during working hours.

But it’s easy to have both too. It’s quite easy to make the whole thing automatic (so even the pilot does not have the ability to turn the thing off) and put the thing in a sealed box (gosh, it already is). Then combine it with a lock and tamper seal and some rules of in which circumstances and by whom it can be opened and it’s contents examined.

I am not a Pilot (IANAP) and this is secondhand, but thanks to youtube the info is out there for all of us to review: https://asrs.arc.nasa.gov/publications/directline/dl4_sterile.htm

A Sterile Cockpit can mean lots of things. But I think it means in this context that conversations in the cockpit while on the clock are always going to be part of the job description – like this article points out, it’s needed in case of accidents. It’s also needed in cases of “near misses” where the accident all but happened, but something prevented it at the last minute.

It must be terrible to be stuck in a confined cockpit for up to 12 hours and not have any privacy. But the alternative is to put all the flights in the hands of an autopilot made by … Boeing, most likely. Shudder!

Kind of like being stuck sitting in the coach for 12 hours and not having any privacy or peace or leg room. Ooorr is that worse?

Yes. On top of that you have to work and it’s terribly boring.

Funny how everyone is ready to throw their pilots privacy out the window when they don’t think for a second about bus or truck drivers not being recorded when they too have a potential to create deadly accidents.

But I guess pilots deserve it, right?

First of all, pilots are “just” “bus drivers”. Except, the “bus” is a bit more expensive. With modern airplanes, a pilot is more of a systems monitor – a study showed, that the actual work load (after pre-flight check) is about 3½ minutes. Most work is done by onboard systems.

However, fully autonomous operation is not currently allowed, so we currently cannot get rid of the pilots. We tried, when I worked in Aerospace… but regulations and humans… :-(

Currently, I work in a Surveillance company. And just by entering the building, you basically sign away all of your rights to privacy – the only places not being monitored are the toilets. There have been some “interesting” post Christmas Party videos…

I dunno what your talking about but your average city bus in today’s day and age generally at a minimum had 4 cameras in it, with one being pointed at the driver. Generally in most cities busses have between 6-10 cameras on them. (Covering the interior, all doors, the driver, straight ahead, and usually a pair of tail cameras facing ahead at 45 to cover the turns the bus makes. In many cases if they have a farebox that takes cash, there will be a camera pointed at it too with the ability to see the driver as well.)

Long ago I saw a British item about a new bus and they just casually mentioned that it had dozens of cameras and not only that but that they also recorded audio…

So if you are in Britain in public assume the cops and government can hear you ANYWHERE.

As for in private locations… there might be a place without cameras and mics, who knows, it is possible, on the moors maybe? You know where pesky UN weapon inspectors commit suicide by stabbing themselves in the back, might not have them there possibly.

And of course it’s known and reported widely that in NYC for instance CCTV also has audio, it’s not just Britain.

(Commercial airline) Pilots need to make less intuitive decisions, faster, in worse conditions, and with both higher stakes and higher standards of performance than a typical bus or truck driver. Bumping into someone on foot can still be a deadly accident if they fall and hit their head or something, but it’s not on the same scale. There’s still an increased danger level between a four-wheeled bus going 60mph on the ground, where a lot of failures only result in pulling to the side and stopping, vs a flying 100 ton cigar going 600mph where you have to maintain a fairly substantial level of mechanical function just to breathe, orient yourself, and affect your trajectory. The fact that there’s not only two pilots but also a certain number of non-pilot crew members should indicate that much like a ship or a tank, the workload can be substantial.

And no, pilots are not just hanging around doing nothing. There wouldn’t be so many indicators and controls and logs and procedure books if there wasn’t a circumstance in which the pilot needed them. A lot of the “autopilot” in normal use is actually just telling the plane where to fly by means other than directly moving control surfaces. E.G. talk on the radio, set the altitude you end up with, take a series of headings, etc. A bit like commanding a ship to proceed with a heading and speed instead of playing with the rudder input and throttle, I assume.

Anyway, it’s been found again and again that the investigators pulling the tapes in case of emergency and letting them get overwritten otherwise is very beneficial. Logically it’s better privacy than say a dashcam that the company reviews constantly or even live.

I and to add you you post (wkpad) that a Sterile Cockpit is only on departure and arrive face of a aircraft and that is not more than 45 minutes of the complete flight.

Beside this there are some rules as don’t talk about politics (internal and normal).

Nobody cares about some guy at macdonald’s being recorded all his working life, but then again they aren’t unionized. I know a truck driver for amazon and he says they record him the entire time, audio video and telemetry. Not the plane though.

Why don’t they just have the NSA pull up the pilot’s phone mic record? Or ping the in-cockpit alexa?

I have no connection to the aviation industry, but have become engrossed in Mentour Pilot‘s videos over the past year. He appears very knowledgeable (being a pilot himself), has a clear passion for the subject matter, and has great presentation skills. That said, I still don’t know why I personally find his videos so addicting, but I highly recommend them if you’re interested in aviation crash investigations and/or also aviation history in general.

It seems that the philosophy of the NTSB is that all airplane crashes are caused by pilot error. That is their first assumption and remains “the cause” unless evidence is found to the contrary. Having more hours of voice recordings capturing every word utter by the cre would most likely give the NTSB more ammo to crucify pilots after crashes or near misses. A bad idea.

Thought hard about this one and I’m with the pilots here.

I work in an operating room and even normal OR conversations, if taken out of context and listened to by the public, would definitely cause so much explaining to happen that it would be useless. I definitely do no want my supervisors listening to everything we discuss in the OR. Half of what we talk about is …them.

That’s not even getting into the discussions with trainees (I’m at a teaching hospital) and the public doesn’t need to hear all the dumb stuff they say, out of context. Pilots are trainees too all the time. The first time a pilot in training may actually fly a jet airliner is likely with a load of passengers in the back.

Plus add the personal discussions with friends that you have worked with elbow to elbow for years. That’s intimate stuff. Relationships, personal health info.

.

No industry scrutinizes its employees to that extent and pilots deserve the same protections and expectations.

How many industries have the same degree of consequences? Not just the plane but everyone else around them.

Many industries have the same degree of consequences. Anything to do with transportation (public bus- could crash into a school). Oil rig worker. Nuclear or even non-nuclear powerplant worker. Any engineer designing things that really shouldn’t fall down. Chemical refinery, chemical plants, anything dealing dangerous materials. Even within aviation, the non-pilots like mechanics, air traffic controllers.

And none of them record the conversations of every one, all the time.

This is incorrect. Most buses these days include driver surveillance. LA Metro has the ability to pull up live video on their buses, including the driver, in addition to recordings.

Importantly, with CVRs, the recordings, unfortunately, are never released. I’ve read many NTSB reports and every transcript seems to be scrubbed off anything too personal. With few exceptions and that’s after years of waiting to get the final report.

It’d be great to have OR recordings that are inaccessible to the administration except in the even of a major medical incident requiring an outside agency to review (AMA?). I think that would improve health outcomes and build public trust, for what it’s worth.

This sounds like the same argument as those against wide-scale CCTV – they don’t want what they do/say in a somewhat limited context (at work in the OR, just out and about in public) being observed by unknown people not present at the time / the public. Of course it depends on the person/organisation in charge of this data to not use it unless necessary but that’s what you need to trust. There isn’t somebody in an office going actively going through every OR recording to look for things, rather should something happens then the recording can be used as evidence.

For CVRs, nobody actively monitors these recordings and as the article states they are recorded over on a loop of X hours. ONLY if there is an incident will the CVR recording be pulled and used, and only available to a very limited set of people.

Wide scale CCTV is too much.

The flight recorders are only accessed when there’s been a real problem – a plane crash with lots of dead people. Privacy is respected in all other cases – you can’t playback the flight recorders and listen to the pilots telling dirty jokes.

CCTV is all over and pervasive and can’t be kept private. The folks monitoring it must watch it, they must see what is going on. They will talk about it and they will spread copies – you can’t prevent it.

CVR, yes because it is only used in restricted circumstances.

CCTV, no because it presents too much scope for abuse.

“Privacy is respected in all other cases – you can’t playback the flight recorders and listen to the pilots telling dirty jokes.”

Troubling to me that on-duty pilots would engage in any such behavior. A higher standard must be upheld for professionals responsible for hundred of lives. If they cannot do their jobs, fire them before they create a critical situation and loss of life.

>Troubling to me that on-duty pilots would engage in any such behavior.

It’s not troubling to me. Let people be human. Professionalism is a cult.

There’s already rules that prohibit nonessential conversation among other things during critical phases of flight. At other times, uncensored idle chatter can be beneficial for interpersonal relations. Anything that keeps them on edge during routine parts of the flight, like paying more attention to what they say than what they do, can degrade their performance in the critical phases.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sterile_flight_deck_rule

Is this sarcasm? Please tell me it’s sarcasm. A pilot can tell a joke on the job. It doesn’t endanger anyone. And why does it have to be a dirty joke anyway? It can be any sensitive information like his embarrassing rash or his child being suspended from school. You’re just being a prude. The pilot’s chatter with the copilot can’t harm you and shouldn’t be morally policed to placate your sensitivities.

The thing of it is that the recordings are only played back when there’s a catastrophe.

The only way to play them back is to open the black box, breaking the seal in the process.

The recordings aren’t there to pin things on the pilots. They are there so that the investigators can get an idea of what may have gone wrong, what warning signals or instrument readings caused the pilots to react the wrong way.

Actually, the CVRs are used in the case of any number of safety issues, not just a crash. But your point still stands.

The reason CVRs are important is that they help to increase the safety of civil aviation. In particular, they help to understand how to avoid the mistakes pilots can make, improve training, aviation systems and cockpit design. As someone pointed out earlier, a lot of times the 2 hour loop has caused vital information to be lost.

Seems like an easy fix. By statute, make the devices the property of the US government and only accessible by authorized agencies for the sole purpose of aviation incident investigations. If the airlines wish to install their own loggers for their own purposes, that is between them and their labor.

The fact that blackboxes need to be ruggedized or “safety critical” is a red herring here, because there is absolutely nothing preventing regulators internationally or only in the US from mandating a ridiculously cheap supplemental sound recorder to exist alongside the older ones that shouldn’t require research or debate.

A $20 used smartphone has the capabilities to record sound adequately far in excess of the longest flights. Add a $100 steel enclosure, and in virtually all crashes where the debris are recovered that would be sufficient to have good info that could data of direct impact on the safety of flights. Similarly, a cheap data storer the size of a usb, encased in some sort of foam to float and avoid hurting people on the ground, with a built in battery transponder, might require some research to safely incorporate into a hull, but it really shouldn’t be a ton.

The real reason this isn’t done is nothing practical, it is regulatory capture, plain and simple. The FAA and others don’t exist to ensure adequate safety at this point, they exist like airport security to reassure the public, to prevent panic among air travelers. Boeing and other manufacturers regulate themselves. The first step is safety suffering, the second is that the public is kept in the dark by otherwise no-brainer design choices like these. The only reasonable explanation modern recording equipment is not on planes is the same as why tamper proof body-cams aren’t universal on cops: they do not want public scrutiny of their misdeeds and failures.

Or just have the IT team push an update to the company iPads most pilots already use during flight.

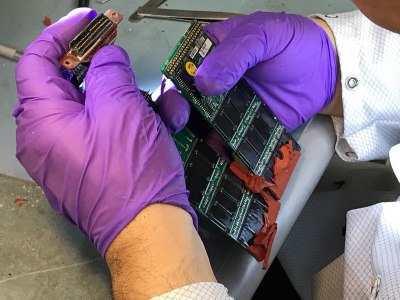

Anybody know why the recovered voice recorder in the last picture is stored in an ice box full of dirty water?

It probably means that the flight recorder was recovered with its case cracked or seals failed, and was filled with seawater. If they just let it drain out and left it exposed to air, the remaining salt water would start to evaporate and concentrate into a corrosive brine, and together with exposure to air there would be rapid corrosion. While it’s submerged in salt water the damage progresses a lot slower. Once they get it back to the lab, they’ll open it under water, flush all the salt away with distilled/deionized water, and then they can safely let it dry.

The Alaska Airlines incident brings up a question: What constitutes a ‘crash’ to terminate recording (and overwrite)? Is it destruction or termination of the power supply to the device? As always it’s possible to imagine edge cases where the system might not perform as intended.

The current level of privacy protections around CVRs seems appropriate- only the committee can listen, a pilot’s union representative is present, and the transcripts are subject to official disclosure rules; these seem like the protections I would want on my own work conversations. Those restrictions should remain in place.

Lengthening the recording time should not magically grant access to the airlines to spy on employee chatter. To prevent the abuse that the pilots fear, additional restrictions should be imposed: the recording hardware must be sealed by NTSB personnel, and can only be accessed and opened by NTSB in case of a major incident. And if the seals are broken, there must be a cockpit indicator that advises the pilots that they’re no longer speaking privately.

I think the more likely explanation is that airline companies are using pilot privacy as a fig leaf to try and avoid liability via “accidental” loss of recordings made on ancient technology

or possibly deliberate loss of recording, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TWA_Flight_841_(1979)#Cockpit_voice_recorder

Don’t know if the pilots can still erase the recording

There’s a tradeoff.

Old style magnetic tape or wire recorders survive mechanical damage and fire better than new style digital recorders, where recovering audio from a crushed IC is basically impossible. If a tape gets mangled and crushed, pieces can be still taken out and the audio extracted, whereas any damage to the chips basically loses gigabytes of data and attempts to read it back from a damaged chip will most likely only destroy it entirely. Electrical damage to a magnetic recorder won’t destroy the recording that was already made.

But fitting 25 hours of audio and flight data onto a magnetic tape that can survive heat and mechanical damage is not easy.

If the tape can be protected from destruction, I’m pretty sure a tiny IC can be too. If nothing else, it can be placed in a box that would take a lot more to destroy. Every media type has it’s vulnerabilities and I think it highly likely that the EU mandate has considered these. I expect a semiconductor based CVR to have a much higher level of survivability than magnetic tape.

The tape may not survive entirely, but parts of it can. If the tiny IC gets crushed, it’s entirely broken with all the data that was on it.

I can imagine an array of microsd card sized flash chips inside protective shells could easily be made to have a statistically better chance of containing any arbitrary critical timepoint, even if each individual chip were all-or-nothing, just because of the stacked up survival probabilities and their small vulnerable point.

on the upside, it’s easy to make data redundant over multiple chips.

…They can make solid-state that can survive being shot out of a cannon or strapped to missiles, I think somebody could figure it out.

It’s one thing to survive the G-load, and another thing entirely to get impaled or crushed directly, or burned, or soaked in petrol etc.

Neat pictures with this.. But now that everything is digital, why not encrypt the data with two keys, the FAA has one and the pilot has the other, perhaps on a barcode in a folded ID tag. The pilots union also has a copy of the pilots half. If something happens, both sides have to come together to get the voice data. If nothing happens, the data is just overwritten. This would keep the voice data private unless there is a need to access it.

…because the pilot died in the accident?

The pilots union also has a copy of the pilots half.

Great answer!

There are already algorithms and key management protocols that can provide this kind of protection while still granting access in extreme cases. It then becomes a political matter of mapping out which parties are required to collude to recover the data.

frankly i dont know why we dont have cockpit, cabin and external cameras on planes, for the same reason. especially cabin cameras might pose a deterrent for air rage incidents. so long as they are only scrutinized in the case of an incident, i have no problem with it.

i dont like surveillance in general and think that the data should be encrypted with keys that only the relevant agencies have access to. even the airline would be unable to decode the data. but i think the general idea is to keep the data in a format that is as raw as possible to aid in recovery, and so that would be counter to the purpose of the units.

You’re not alone; the NTSB has been calling for cockpit video recorders for decades.

https://www.flightglobal.com/safety/ntsb-again-calls-for-cockpit-video-recorders/143210.article

The answer is surely not longer recordings, but recordings which are only erased when explictly commanded to do so. Have the recorder last for the length of the flight, if they land without trouble the pilot presses an erase button. That way one need not worry about the recorder keeping running on the ground and overwriting important stuff, but clearing any private talk will be easy.

That doesn’t help when a problem isn’t immediately obvious.

Sometimes after a major event they audit similar aircraft looking for patterns. Or the accident aircraft’s previous flights.

I get the impression minor stuff happens all the time- who is to say what constitutes “erasable nevermind” vs “potentially useful.”

Perhaps a 3 year time frame for mandatory record keeping, similar to mandated possession of maintenance logs etc would be helpful in those edge cases.

I can easily see both sides of this argument.

Unlike most workplaces, there isn’t any place a pilot can “disappear” to in order to have a quick “off the books” discussion with a colleague. They can’t just pop out to the dumpsters to have a smoke and complain about their boss.

I think the real resistance is the constant “mission creep” that we all see around recording technology, everywhere in our lives. Whether it’s in our jobs, out in public, cars, or even just in our internet or TV viewing habits, gigantic collections of information are being amassed, and are now frequently being misused for purposes it was never meant to be used. For example, the cute “work around” where the NSA is buying private data that they’re forbidden from collecting.

They’re (the pilots) responding to the constantly changing rules that govern when it’s appropriate to listen to the recordings, and they rightfully don’t trust that the powers in charge will restrain themselves to do the right thing in the future. There’s always some great reason to expand the surveillance once it’s in place…always one more important thing that will magically be solved by listening in. It’s always “think of the children” or “keep us safe from terrorists”. They (the pilots) see that the compiled recordings are just too tempting a target, and they recognize that the people in charge are just like themselves…curious voyeurs who could be swayed by some reporter to release comments about their home life to the press. Perhaps an enterprising lawyer might access the tapes in a divorce proceeding? Perhaps the FBI would get access to the tapes to investigate a pilot? Perhaps the FBI already does?

I’m pretty sure that a lot of this resistance would disappear when we start seeing more restraint in how collected data is used. When people generally believe that “no means no” when confronted with mission creep, they will be more open to saying “yes” for it’s intended purpose.

elegant and thoughtful. thank you.

With the rise of Starlink, etc, I don’t understand why flight data and cockpit recordings aren’t live streamed to a ground station? Sometimes you don’t find the black box, imagine what satellite transmitted data would have done for the flight 370 investigation?

Probably not much, since the satcom links the aircraft did have appear to have been intentionally disabled.

Well if it was an emergency system the pilots shouldn’t be able to disable it.

I think pretty much everything can be disabled by pulling a circuit breaker, if there’s some faulty circuit potentially causing a fire you need to be able to turn it off

>25-hour recording window

Too expensive, thats almost 2GB of flash! And dont even think about 7 day buffer, 16GB of industrial grade SLC flash would cost a fortune, a $200 to be exact!!1

Considering how expensive a commercial airliner costs these days, the cost for even best-in-the-world gold standard flash memory shouldn’t be a concern.

Ah, yes, no-one has ever figured out how to compress digital audio, and $200 is obviously too large a fraction of the cost of a jet airplane.

See I like this comment. A guy using sarcasm to respond with complete sincerity to another post that was extremely obvious sarcasm. It has a kind of poetry to it, a symmetry. Beautiful.

This post is very sturdy and metallic… tastes like iron-y.

Do people remember this story about pilot plane chit-chat that was recorded?

https://abcnews.go.com/Travel/story?id=7560379&page=1

Privacy is a human right. Human rights don’t void because you happen to have a particular job.

This thread has suggested surveillance in almost every way possible already – but only in case of an “incident” and only by the “right people”.

Isn’t it lovely how “incident” and “right people” have shifted over the last 50 years. USA was different 50 years ago. Iran was also very different 50 years ago.

At the basic level, it’s hard to decide what’s private about what the company’s crew is doing while flying the company airplane with a load of the company’s passengers in back. Even so, there are serious efforts to protect original recordings from disclosure, and to redact from transcripts anything that is truly private/personal. All rights have exceptions and limitations, and the safety information gleaned from CVRs and flight data recorders has been invaluable for saving lives over the years.

Scratching your ass is a human right but you should wave that right when you’re doing surgery.

yea but the reason air travel is as safe as it is now, is because we have scrutinized every incident with extreme scientific rigor. but it is a slippery slope indeed, and it always has been. it can prove you innocent or guilty. or someone can use it to build a false narrative where you’re the hero/villain.

people who work in convenience stores have cameras pointed at them all the time and practically no regulations about what you can do with the footage, and they aren’t responsible for a multi million dollar aircraft and over a hundred or so passengers. i like the idea of using encryption, but who is more likely to throw you under the bus, the government or your employer? i dont trust either these days.

“Air Disasters” is an extremely well done series on the Smithsonian Channel with 20 seasons thus far:

https://www.smithsonianchannel.com/shows/air-disasters

“Mayday: Air Disasters,” a Canadian series, is also good and can also be found on-line.

From watching those, I can say that the NTSC is the only federal agency that I trust 100%.

Absolutely my favorite TV show.

I always wonder why there is no backup on the cloud.

Nowadays we do have internet on planes, so it’s impossible to stream black box data on the cloud?

Of couse we still need the physical black box, since, probably, the internet connection drops in case of accidents.. but still seems to me a nice feature. Or am I missing something very important?

Cost and bureaucracy. This will be mandated for every plane in the US. Consider that we’re currently struggling to upgrade from 2hr to 24hr. It’ll take another big effort to get the internet backups.

Because if the system is too reliable, they wouldn’t be able to plausibly lose data which embarrasses them or opens them to lawsuits.

i don’t even trust the cloud for my saved games, let alone my flight telemetry.

It is mostly because of jurisdiction. Who stores the data?

The airline? The plane manufacturer, the government?

With planes flying internationally, which government should store the data?

Do you trust any of the above from “filtering” or releasing any potentially embarrassing data?

Cheap as they oughtta be — pretty basic tech — I’m surprised they are not required in the cars we drive today. Might be interesting for cops or insurance critters to hear what was going on inside or last words just before the

silence

The passengers have to get irradiated, groped, and se×ually assaulted just to get on the plane. The pilots can suck it up about their privacy feefee’s getting hurt to do a job with hundreds of lives at stake.

“the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), aircraft with a maximum takeoff weight exceeding 59,500 pounds ”

Yeah right. I’m sure the Europeans are doing this instead of using 27,000 kg.