Since the crew at [CPSdrone] likes to build underwater drones — submarines, in other words — they need to 3D print waterproof hulls. At first, they thought there were several reasons for water entering the hulls, but the real reason was that water tends to soak through the print surface. They’ve worked it all out in the video below.

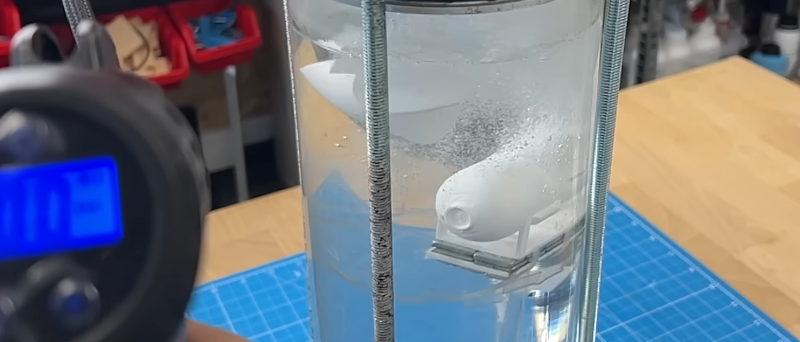

Since the printer is an FDM printer, it isn’t surprising that the surface has tiny pores; even the tiniest pores will let water in at high pressure. They tried using epoxy to seal the prints, which worked to some degree. They did tests using an example submersible hull that you can try yourself if you like.

It took quite a few tests to find leaks. At 10 cm of water pressure, the prints did well. However, the deeper you go, the more pressure is on the hull, and you get more water inside or, at least, soaked into the plastic. To figure out the difference, they repeated the tests with solid models and found that some water gets inside and some of it is soaked into the layers.

The next step was experimenting with dichtol, a smelly chemical that waterproofs prints via a soaking process. Repeating the experiment showed very little water ingress, even at high pressures. The dichtol soaks into the plastic like water and leaves behind a resin when it evaporates.

The final step was to try a resin print. The results were a little skewed because the hull was still full of resin, which didn’t allow for a full test. The resin wasn’t very strong. However, they also had some engineering plastic models made and — again — reran the experiment.

If you need to put things underwater, you’ll be interested in these results. We’ve seen the guys do underwater drones before. They aren’t the only ones, of course.

xD

….. Now make it 20x bigger !!

What a great idea! Will you let me ride in it?

Only if you’re a billionaire.

Only if you’re a billionaire

I wonder how well a 3d printed sheet would remove salt or bacteria from water.

You can use 3d printing to make fine filtering mesh by having the printer stretch multiple layers of filament across an open span.

https://hackaday.com/2023/04/16/3d-printable-foaming-nozzle-shows-how-they-work/

I was thinking the same thing for a moment there, but then it hit me – the idea of potentially consuming higher levels of microplastics doesn’t sit well with me. Given what’s been discussed the tendency of 3D printed objects to shed microplastics more than other items, it raises concerns about their safety for water filtration uses. It’s a reminder of the trade-offs and considerations we have to weigh with innovative solutions. Other options like using clay pots and ceramics that might be better for the environment.

Short answer is no. Besides the large amount of plastics and energy required for everyday use of such filters, the holes are not small enough to filter efficiently and even if they could be, there is no hole size stability (is enough a large one to let salt water contaminate the main product).

Better search for a material (plastic maybe) that foams while printed thus forming the filter, but the recycling question remains.

And replace them with tons of microplastics

Maybe draw from the wisdom of maritime oldtimers. Linseed oil would be fun to try as a sealer. On air contact it polymerizes to a hardy, waterproof, insoluble layer, but still remains somewhat flexible to accommodate creeping and flex.

Interesting thought, and the sort of thing that is forgotten far too often. The folks of the past didn’t have petrochemicals, yet faced many of the same problems. Their solutions are often elegant, effective, safer, more durable, cheap at small scale being more directly processed from natural sources. Though obviously they are not always better, rarely as fast etc – but still worth learning about them and considering them.

I suspect linseed wouldn’t be durable enough in this case, but really worth trying still. Those small pinholes its covering have 1atm behind, but many times that on the other side at depth and I doubt it will penetrate the FDM much to be more than a very thin layer on the surface…

I have used Urethane sealant on prints to make them sealed and shiny (Hovalin, 3d printed violin). I had thought about dipping the whole part in…or as others have mentioned below…maybe some sort of vacuum to pull the liquid in. Vapor deposition maybe?

Worth playing with.

Well, if you go down the road of vapor deposition then you might consider Parylene. Fantastic stuff, essentially impermeable, pinhole-free, but not exactly simple DIY. Also not terrifically robust mechanically in our experience, despite claims by coaters. It would require mechanical protection if you’re bumping a sub off rocks, etc.

I was thinking more along the lines of melting the surface or even coating it in something like nail varnish. I wonder what effect acetone smoothing has on the porosity of 3d prints. Perhaps putting them in a vacuum chamber and potting them in resin.

Good call. Also note tung oil retains more flexibility and cracks less over time than linseed oil.

Coat the sub with epoxy, do a vacuum purge to pop most of the bubbles in the liquid epoxy, then cure at atmospheric pressure.

Air pressure should force the liquid epoxy into the pores of the submarine.

THIS is the right direction! Unfortunately, regular epoxy will be too viscous. Adding solvents to regular epoxy won’t solve the problem, as they’ll leave voids on evaporation. Polyester resins can be made very viscous, but can require heat to cure.

dichtol is cool, but you could probably achieve the same results by using a 1 mm — 1.2 mm nozzle with plastic that is not hygroscopic and some sort of sealant that is compatible with the plastic used to print. I would like to see a video comparing high strength UV resins. I would also like to see a test with polyetherimide & peek…

Waterproofing a print is cool and all. Basically, the same thing as smoothing though.

But if your objective is to build underwater drones, a trip to the plumbing department might be a better move. People have been building RC submarines for 50 years. Protip: Recovery boey and boat on hand.

Also: Alligator decoy submersible. For fun at the river.

I wonder if the methods of [DaveMakesStuff] would be useful in this instance?

https://hackaday.com/2024/01/13/tips-for-3d-printing-watertight-test-tubes/

Don’t know these have been tested against any significant pressure.