In the 1967 movie The Graduate, a wise older man gives some advice to the title character: plastics. Indeed, plastics would become big business. In 1962, though, a computer-savvy character might have offered a different word: transfluxor. What’s a transfluxor? Well, according to computer history sleuth [Ken Shirriff], it was the heart of a 20-pound transistor computer from Arma. Of course, plastics turned out to be a better bet, but in 1962, the transfluxor seemed to be the wave of the future.

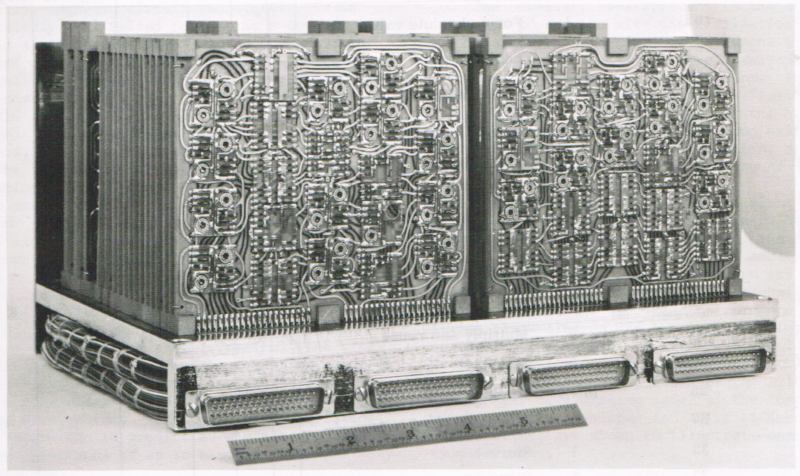

In 1962, most computers were room-sized, but the Arma was “micro” taking up just 0.4 cubic feet — less than an Apple II. It would eventually spawn computers used in ships at sea and airplanes ranging from the Concorde to Air Force One.

The computer was a bit odd since it had a 22-bit word, and it processed them one bit at a time. Serial computers like this were relatively common in the early days of computers because it dramatically reduced the gate count — important when trying to cram transistors into a tiny box. Of course, the serial data path meant the 1 MHz clock was quite slow. The machine only did about 36,000 instructions per second. While it only had 19 instructions, some of them were more powerful than many computers of the day. For example, the machine could multiply, divide, and even do square roots.

Another space saver was the use of DTL or diode-transistor logic. The computer had wafers, which were tiny circuit boards with just a few functions. The wafers were mounted on boards like ICs, and the board was attached together and coated. The computer could handle shock, temperature, humidity, and even vacuum.

Another space saver was the use of DTL or diode-transistor logic. The computer had wafers, which were tiny circuit boards with just a few functions. The wafers were mounted on boards like ICs, and the board was attached together and coated. The computer could handle shock, temperature, humidity, and even vacuum.

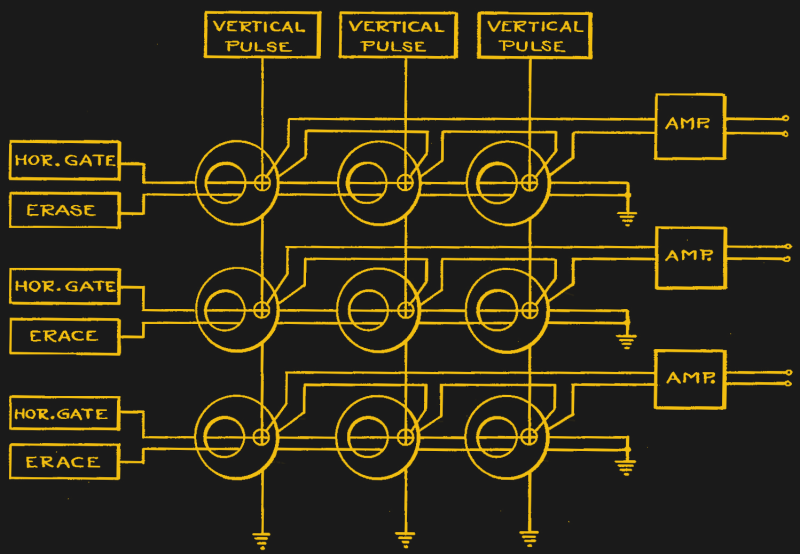

So what’s a transfluxor? You can read [Ken’s] post, but essentially it was a special type of core memory. Normal cores are like a donut. A transfluxor core is like a donut with a big off-center hole and a smaller hole near one edge. You write to the core through the big hole and read through the small hole. Along with some extra circuitry, this allowed the core to be read without destroying the stored data.

There’s a lot more information about this computer, the company behind it, and the later versions of it in the original post. We always enjoy [Ken’s] musing, which ranges from inside ICs to more conventional core memory.

Darn. And here we was hoping for time travel.

Wtf is erace or a HOR gate

in this case, it’s likely to be Horizontal Gate, given the perpendicular lines labeled Vertical Pulse.

I would have thought it was a weird font or typo for “NOR”, but from the patent the image is taken from it’s short for “Horizontal gate” — a gate that’s pulsing all the cores in that (horizontal) row.

(“Erace” is just a typo for “erase”, also judging by the patent.)

Was the article supposed to explain transfluxors or is my expectation unreasonable?

At a guess the article was supposed to be a teaser to give you enough info to decide if you wanted to click the link in the first paragraph that is a deep dive into a transfluxor. It would hardly make sense (or be honest) of them to try to replicate the in depth content into their article, so if you expected them to do so then I’d say yes, that seems unreasonable. I would like to cite this though from the article:

“So what’s a transfluxor? You can read [Ken’s] post, but essentially it was a special type of core memory. Normal cores are like a donut. A transfluxor core is like a donut with a big off-center hole and a smaller hole near one edge. You write to the core through the big hole and read through the small hole. Along with some extra circuitry, this allowed the core to be read without destroying the stored data.”

It literally explained it AND included a diagram! It’s a type of core memory. Core memory used a metal donut for each bit, which it magnitized to store a bit of data. Reading a bit de-magnitized the donut, so a bit of data had to be re-written after it was read. In a transfluxer memory, the sense wire ran through a separate hole, so the bit could be read without de-magnitizing the donut.

But, it became irrelavent because transistor based DRAM was invented just a couple of years later, making core memory obsolete.

That’s neat and all but what about a deep dive on interocitors?

Or squegging oscillators?

A capacitor and inductor in one device: the incapacitator.

This made me laugh out loud