We all know how a conventional internal combustion engine works, with a piston and a crankshaft. But that’s by no means the only way to make an engine, and one of the slightly more unusual alternatives comes to us courtesy of a vintage Shell Film Unit film, The Free Piston Engine, which we’ve placed below the break. It’s a beautiful period piece of mid-century animation and jazz, but it’s also an introduction to these fascinating machines.

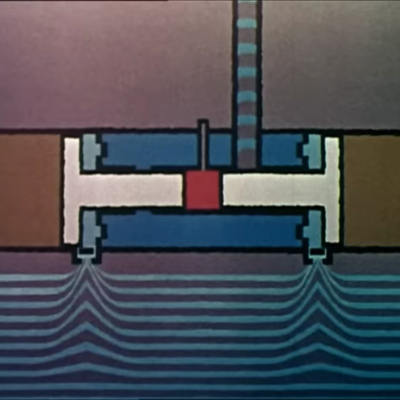

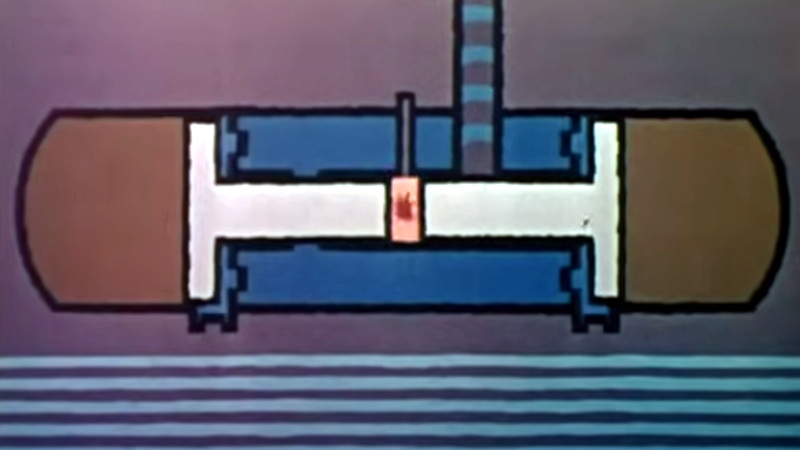

We’re introduced to the traditional two-stroke diesel engine as thermally efficient but not smooth-running, and then the gas turbine as smooth but much more inefficient. The free piston engine, a design with opposed pistons working against compressed air springs and combining both compression and firing strokes in a single axis, doesn’t turn anything in itself, but instead works as a continuous supplier of high pressure combustion gasses. The clever part of this arrangement is that these gasses can then turn the power turbine from a gas turbine engine, achieving a smooth engine without compromising efficiency.

This sounds like a promising design for an engine, and we’re introduced to a rosy picture of railway locomotives, ships, factories, and power stations all driven by free piston engines. Why then, here in 2024 do we not see them everywhere? A quick Google search reveals an inordinately high number of scientific review papers about them but not so many real-world examples. In that they’re not alone, for alternative engine designs are one of those technologies for which if we had a dollar for every one we’d seen that didn’t make it, as the saying goes, we’d be rich.

This sounds like a promising design for an engine, and we’re introduced to a rosy picture of railway locomotives, ships, factories, and power stations all driven by free piston engines. Why then, here in 2024 do we not see them everywhere? A quick Google search reveals an inordinately high number of scientific review papers about them but not so many real-world examples. In that they’re not alone, for alternative engine designs are one of those technologies for which if we had a dollar for every one we’d seen that didn’t make it, as the saying goes, we’d be rich.

It seems that the problem with these engines is that they don’t offer the control over their timing that we’re used to from more conventional designs, and thus the speed of their operation also can’t be controlled. The British firm Libertine claim to have solved this with their line of linear electrical generators, but perhaps understandably for commercial reasons they are a little coy about the details. Their focus is on free piston engines as power sources for hybrid electric vehicles, something which due to their small size they seem ideally suited for.

Perhaps the free piston engine has faced its biggest problem not in the matter of technology but in inertia. There’s an old saying in the computer industry: “Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM“, meaning that the conventional conservative choice always wins, and it’s fair to guess that the same applies anywhere a large engine has been needed. A conventional diesel engine may be a complex device with many moving parts, but it’s a well-understood machine that whoever wields the cheque book feels comfortable with. That’s a huge obstacle for any new technology to climb. Meanwhile though it offers obvious benefits in terms of efficiency, at the moment its time could have come due to environmental concerns, any internal combustion engine has fallen out of fashion. It’s possible that it could find a life as an engine running on an alternative fuel such as hydrogen or ammonia, but we’re not so sure. If new free piston engines do take off though, we’ll be more pleased than anyone to eat our words.

Stirling free piston engines, that couple energy out through linear magnetic arrays, seem to be at least competitive for some industries and business cases where very low vibration is necessary. They’ve been developed for use in satellites, running off radioisotope heat, and NASA seems pretty enthusiastic about them.

Or..

https://www.osti.gov/biblio/6003579

Cap

Remember the original article in the 70s mechanics illustrate, a few of us on board ship tried to build one off of prints

Oh look

https://www.spudfiles.com/viewtopic.php?t=27010

William Beale invented the free piston Stirling engine, or was the main inventor and improver of it. There is a fine book about Beale and his company Sunpower, “The Next Great Thing” by Mark L. Shelton [1980].

How do I get the book “the next great thing “?

I don’t get it. Why go through all that trouble to make compressed hot gas, if you’re not going to use the mechanical power from the pistons?

Surely a well-engineered combustion chamber can produce hot gas, and do so more cleanly and with less complication.

Yeah… feels like something a few pulse jets tied together could do just as well if you could ‘average out’ their impulses to get smoother output.

A combustion chamber on its own makes atmospheric-pressure hot gas, and is also called a flame. You get some compression with pulse jets, but only as much as the sound pulses are capable of. You get some also with that one pressure jet that uses both sound waves and a pressurized fuel that inducts air when injected. A piston engine can suck in its own air and then compress it 10-20x (gas vs diesel, to the nearest multiple of ten) with plenty of leftover energy after the fuel is burned to drive the crank or an exhaust turbine. The turbochargers in cars don’t get 10-20x compression in a single stage, if you take “x” to be sea level atmospheric pressure and think about how much pressure that would be. That said, piston engines are not so perfect as to not benefit from having a turbocharger added to take up some of the total compression and expansion instead of doing it all at once.

Free piston sterling cryocoolers are pretty common if you don’t want to use liquid nitrogen for cooling. I’ve seen it in communications equipment and lab equipment.

Ditto about the first comment from ‘smellsofbikes’. I was wondering what happened to it. The satellite was covered in a 1981 Design News magazine. It was supposed to operate an extremely long time.

Put a linear coil on it and use as a generator for electricity?

I had an idea like this. However, instead of a gas turbine, put a strong magnet on the pistons, and a coil of wire in the jacket. Now extract the energy from the engine as electricity. A perfect Hybrid auto engine. What little fuel you use, you use efficiently. The magnets, and coils might be able to replace the compressed air chamber.

I also had that similar thought, and the problem I saw was that the temperature in that environment would cause permanent magnets to lose their magnetism. It may be a surmountable problem, but it is a problem…

If you have some smart electronics added, you could also vary your load periods such that the synchronization linkages also becomes obsolite.

I have spent some time in the past thinking about this type of system, and an application that seemed ripe for maximizing its potential is long-haul trucking where the power source could be incorporated into the undercarriage of the trailer and the very long available travel of the piston might allow for more efficient capture of the energy produced by the combustion. (With that in turn producing electricity for driving electric motors in the tractor which could also benefit from the very high torque output available from electric motors).

Not so coy, some details on Libertine’s technology in this tech blog I posted on LinkedIn a little while back :)

sam-cockerill-7203982_lineargenerators-renewablepower-technologydevelopment-activity-7121158426822328320-gL5e

Inertia can be a problem for both Linear Generator adoption and commercialisation and (literally) for free piston motion control. It used to be said that “motion control is where free piston engine dreams go to die”. Not anymore.

The key is to integrate high force per unit mass linear e-machines with best in class embedded controllers and recent advances in power electronics.

Once more, with the full link this time;

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/sam-cockerill-7203982_lineargenerators-renewablepower-technologydevelopment-activity-7121158426822328320-gL5e?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop

I think the Batmobile uses free piston gasifiers. These would turn a turbine which supplies electrical power to all other systems. The four wheels and the compressor would have independent electrical motors. The compressor would be of the same type as a turbo jet engine, allowing the air to pass through without turning 90 degrees.

Having multiple free piston gasifiers would also lend the Batmobile a high degree of redundancy, since only one would be necessary to drive the vehicle. Also, they can be switched off independently, which would provide greater fuel efficiency for longer trips. The front compressor could also be switched off in such case.

With this type of arrangement the Batmobile could have two separate throttles: one connected to the free piston engine and operated by hand, modulating its total power output, and another connected to the electrical motors of the wheels and operated by foot, which allows for fine, intantaneous power modulation.

Tom Braun had many working examples of the free piston engine compressors. The balanced masses of the engine and compressor meant running at any frequency one could balance a nickel on edge of a running machine.

Mike Tate