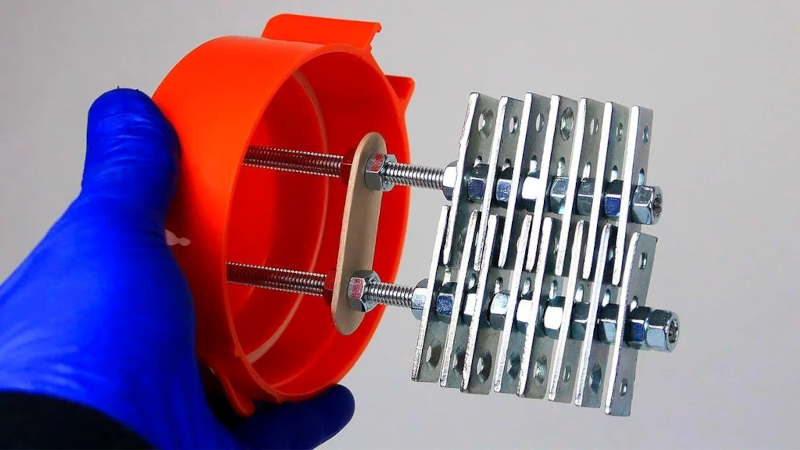

In theory, water and electric current will cause electrolysis and produce oxygen and hydrogen as the water breaks apart. In practice, doing it well can be tricky. [Relic] shows an efficient way to produce an electrolysis cell using a few plastic peanut butter jars and some hardware.

The only tricky point is that you need hardware made of steel and not zinc or other materials. Well, that and the fact that the gasses you produce are relatively dangerous.

To that end, [Relic] includes an “I don’t want to explode switch” in the system by routing tubes of gas through a second jar filled with water so that the water will block its return.

Of course, we’ve seen the same setup created with a battery, two coils of wire, and some test tubes, but this can certainly produce more hydrogen faster. Like most of these designs, you can scale them by adding more steel parts. The more surface area, the more gas you’ll produce.

We’ve seen a number of similar generators before, but each one is a little different. If you want to get really fancy, you can turn to automation.

When I made a hydrolysis machine when I was a teenager (13-14?) I had a lot of problems with corrosion. My solution was I pulled the carbon rods of the D cells. I very tightly tied stranded copper wire that I stripped a few inches (just a bunch of granny knots). And covered the connection with epoxy. That did the trick. No more weird green smelly water that was probably poisonous. Some white film still formed on the surface, but I had to run it hard for quite a while to get that.

A small plastic toy hand pump and I was able to get some balloons to float. Even with ear protection they were horribly loud when lit. But putting a little H2 in a test tube and lighting that got me the nice slow burn to confirm I did manage to collect decently pure H2 gas. (a fast burn would have indicate that it was contaminated with oxygen)

Electrolysis, not hydrolysis.

A hydrolysis machine is used to decompose organic matter, like dissolving dead pets or converting wood into ethanol.

Something that should work easier: buy a pack of wooden pencils, burn them and collect the graphite cores.

Now you have a bunch of long uniform graphite rods.

Granger sells graphite rod as well as tubing, bars and flat sheets.

Grainger sells those plates they put on doors to push on that are made out of stainless steel

Pencil leads used as electrodes will soon end in disappointment. They are either made from a mixture of graphite and clay or graphite and polymer. Both will disintegrate quickly, the clay adding iron, calcium, magnesium, etc ions into solution, the polymers will delaminate. The high current density (small surface area) will speed up disintegration especially at the anode. They also have high resistance. Use good graphite rods like welding electrodes instead.

The tin lining of “tin” cans is a good electrode material. Electrical tape on the edges to prevent other reactions. And the tin doesn’t react quickly with oxygen, so you can collect O2 and H2 if you wish. Sodium hydrogen sulfate—sodium bisulfate or solid “pool acid”— or washing soda—sodium carbonate—as the electrolyte. Safer than H2SO4. Did that one over a half-century ago. The instructions were in my science book…How times have changed.

Most “tin” cans made in the last half century or so, at least the ones for food, have a very thin plastic lining that you’ll need to get rid of.

The author correctly recommends not using zinc electrodes, but they failed to mention the other potential heavy metal contaminants such as nickel or chromium. Electrolysis chemistry is complex and using hardware store materials introduces many unknowns.

Do NOT use stainless steel for electrodes under any circumstances (https://www.osha.gov/hexavalent-chromium). Check the composition of all alloys used in the electrolysis cell. Handle and treat byproducts having heavy metal contamination as required by law. Consult the established literature. Use proper PPE.

Lol. Somebody’s scared of a little Cr(VI)

You bet I’ll keep harping on being careful with chromium poisoning. I lost an uncle to cancer caused by occupational heavy metal exposure in the auto and machining industries. He was 43 years old.

Sure. Play with stuff. Maybe have fun. Maybe mess up your own life. Just don’t dump your experiments down the storm drain and contaminate the water table that me, my children, my neighbors, or the local wildlife have to drink from.

You drink groundwater? I purify all water with a distiller, even tap water. I don’t trust the groundwater or what comes out of the tap.

I came here to write this; I’d rather someone take the zinc off a piece of steel that doesn’t have significant chromium or use pure nickel than to intentionally seek out chromium even though stainless steel is cost effective. If they don’t mind it working not quite so well, just use carbon. I could react out any chromium before disposal, but other people won’t. And using a thin plastic container only works if you’re not going to have extreme enough conditions to embrittle or dissolve it. The most effective common conditions for this are to use highly saturated lye (preferably potassium lye) and nickel, then allow it to reach high temperatures. Guess what is really corrosive – hot bubbling concentrated lye…

Plus, this thing is not the best of the similar designs – others get better surface area proximity. If you just want to do dumb things without worrying about efficiency, you can get the conductivity up enough to not need lye with a different setup.

We did it with a peanut butter jar which was plastic. After a while it got warm and the jar softened and the electrodes touched and we got a big bang.

Yes, the chromium and nickel are bad for you, and we all know there’s no such thing as free energy.

But, since we are going to play with stuff like this anyway, here’s some tips from my own experiments:

316 stainless is good. 304 stainless doesn’t produce much of anything. Stop at a welding shop and ask for a couple of 316 stainless filler rods. Diameters of 3/32″ or less and you can shape it by hand – coils, zigzag, whatever.

Where would you get a compressor safe for H2?

Harbor Freight. Safety is relative.

real Cheap H/F compressor is oilless, which is a rubber diaphragm pump with plastic one way valves, so the explosion risk is pretty low. Just depends on how well you modify the intake to not let any atmosphere in.

electrodes ..or.. air gap capacitor?!

Posts picture of zinc-plated hardware (BZP)

So is he gonna die or???

It should be mentioned what type of drain cleaner. Most brands contain sodium hydroxide (lye) but some are sulphuric acid (at least in my locale UK). A little of either would reduce the resistance and increase the production, but the acid would dissolve the steel much more quickly.

PS I’d really like a mod that collected the oxygen and hydrogen separately, without reducing efficiency too much.

Doesn’t anybody remember cold fusion around here? Platinum electrodes, and cast. The little pores in the surface of the electrode make your energy go a little farther.

use Aluminum cans instead.

https://news.mit.edu/2024/recipe-for-zero-emissions-fuel-with-cans-seawater-caffeine-0725