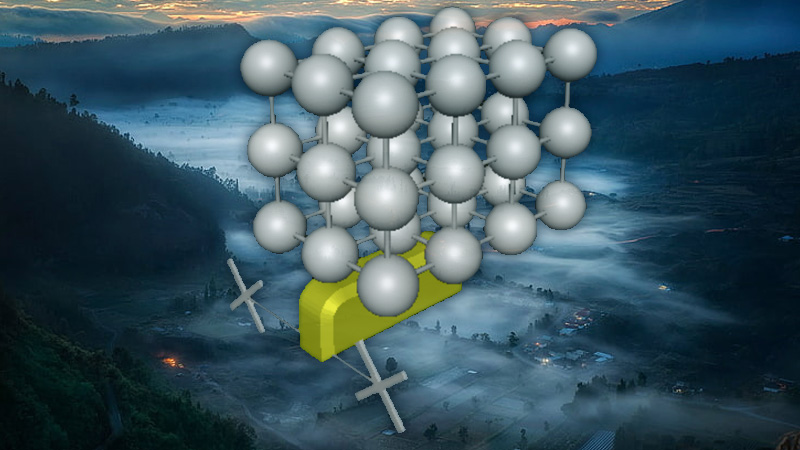

If you’re looking for an intriguing aerial project, [DilshoD] has you covered with his unique twist on modular airships. The project, which you can explore in detail here, revolves around a modular airship composed of individual spherical bodies filled with helium or hydrogen—or even a vacuum—arranged in a 3x3x6 grid. The result? A potentially more efficient airship design that could pave the way for lighter-than-air exploration and transport.

The innovative setup features flexible connecting tubes linking each sphere to a central gondola, ensuring stable expansion without compromising the airship’s integrity. What’s particularly interesting is [DilshoD]’s use of hybrid spheres: a vacuum shell surrounded by a gas-filled shell. This dual-shell approach adds buoyancy while reducing overall weight, possibly making the craft more maneuverable than traditional airships. By leveraging materials like latex used in radiosonde balloons, this design also promises accessibility for makers, hackers, and tinkerers.

Though this concept was originally submitted as a patent in Uzbekistan, it was unfortunately rejected. Nevertheless, [DilshoD] is keen to see the design find new life in the hands of Hackaday readers. Imagine the possibilities with a modular airship that can be tailored for specific applications. Interested in airships or modular designs? Check out some past Hackaday articles on DIY airships like this one, and dive into [DilshoD]’s full project here to see how you might bring this concept to the skies.

Interesting concept. The redundancy of lifting bodies reduces the potential for a single failure being catastrophic. Can the vacuum container be made lighter than a helium/hydrogen envelope? (Nonvariable ballast) The pictured concept is going to generate more drag than an aerodynamic envelope.

and vacuum needs way stronger materials to keep the shape. maybe fill them with Vacuum Foam™? ok. kidding aside, the idea is nice for an “what if” article by Randall Munroe. but there it stops. was this dreamed up by an llm?

the more surrounding material you use to envelope a bouyant space, the less efficient the whole thing becomes. a single sphere uses the least amount of material and hence is the most efficient. graf von Zeppelin calculate all this more than 100 years ago. vacuum is more bouyant, but the forces on the volume are very high and difficult to manage. that’s why you fill the space with less efficient gases: you need drastically less materials to keep the volume from being crushed by the air pressure. 1 bar is nothing to laugh at.

You could do it in stages, so have an outer envelope with 0.8 bar for example.

Also I like the idea of a He envelope surrounding an H2 one. Occasionally you’d return to bbase and replenish the gases so you could purify out the diffused He into H2 and vice versa.

Then you’ve multiplied the weight of the envelope many, many times. For an extremely small lift gain

Redundancy isn’t a new concept for lighter than air craft – all the ridged frame zepplin style had many sacks as far as i know wrapped in the aerodynamic shell, and I think a few of the soft skins at least have multiple balloons in them.

No, vacuum balloons are a really dumb idea. Even if you could engineer such an envelope and make it somehow within 5% of the weight of a passive gas bag (completely impossible) the lift gains over helium would be just a few percentage points

Can we use leather bladders, with ropes, brass fasteners, and mahogany? And gears! But, only if they do something.

I believe it to be a necessity.

And the proper formal attire (top hat, waist coat, ruffle shirt, cravat tie) with goggles to fly it.

Zeppelins used leather gas bags–specifically goldbeaters’ skin.

It would work if there is 99 of those ballons, I guess.

+100

If that comment is not “read” is it still funny?

I’d “go buy” that.

(Ugh, clicked the “Report comment” link by mistake. Is there a way to undo that? Nothing stands out.)

Yeah I’m honestly confused by who would be fooled into thinking this is a good idea. I’m also open to selling someone a barrel of water but I plan to convince them my barrel is more efficient because instead of one big barrel of water I made 50 smaller barrels and then tied them all together.

Right?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Square%E2%80%93cube_law

Windage may make this a viable option sometimes – usually you have a pointy rugby ball sort of shape to your airship to get ‘good’ aerodynamic performance in the direction you want to go. But that does mean crosswinds have much more to work on.

Also the surface area of the materials going into the envelope isn’t the only consideration – if these small spheres can be made cheaper, more durable, and use less dense materials to be that way then the lifting body size may actually be able to shrink as the total mass of envelope required to handle all the forces applied actually goes down even though the surface area goes up.

Not saying I’m convinced, but won’t dismiss the idea out of hand either.

Alas, a pioneer who was hoping for higher things, had his hopes dashed, and his faith in this system plummeted.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adelir_Ant%C3%B4nio_de_Carli

I was thinking of the movie up. Your link is a really sad (more realistic) version of the same.

I looked up weather balloons (which I have no experience with)… They typically carry small loads, like 1kg when going to very high burst altitudes, or maybe 25kg if not going very high. The number of balloons that would be needed for this grid approach would be gigantic, particularly to support the framework to scaffold the balloons together.

I applaud the creativity, but the physics don’t seem to be well considered.

My first thought as well. As Elliot linked off to, it’s the square-cube relationship. There’s also absolutely no way that cartesian-axis grid, especially of flexible connecting tubes, would be stable, especially once you sail into any kind of gusting/turbulent air. It’d break up in a heartbeat under anything but a physicist’s idealized conditions.

OTOH, spheres are the ideal pressure vessel. If it enabled partial vacuums (a real stretch), maybe there’s something to be gained.

OTOOH, commercial airships aren’t a thing, stop trying to make commercial airships a thing. Just use seagoing vessels (just please transition away from bunker fuel).

Quick math: from the io page, the mass of a balloon is estimated at 375 to 900g for a 470 to 600cm circumference sphere (why define it by circumference? Weird). I find that mass estimate to be completely unreasonable, but whatever. I went with the top of both ranges, but again, I think that mass is impossible.

At atmospheric ASL conditions, this gives a hypothetical payload at neutral buoyancy of 192kg. This would include the support structure, gondola, propulsion, etc. There’s no real way a useful gondola would weigh less than 30kg, and the support structure would be significant, let’s say an extremely optimistic 50kg. Add on motors and energy supply (really would have to be fossil fuel for specific energy), and you can’t cover any significant distance whatsoever empty, let alone carry things. And this is neutrally buoyant at sea level with no margin, an impossibly optimistic point of analysis.

Fact of the matter is, commercially viable airships simply aren’t possible at this scale. Even with a much more efficient traditional envelope design, they need to be much, much, much larger to approach making sense

I was debating about whether to say this, but I feel compelled to: The IO page itself says that this is cribbed from a rejected patent application in Uzbekistan. It then links off to the io page author’s GoFundMe.

Like, the patent was rejected for a reason, it’s about as valid as a perpetual motion machine. And then it looks like this guy literally copy pasted it (the language looks to be an exact google translation of the original patent) to get eyes on his GoFundMe link. Maybe I’m misreading this, but it doesn’t feel like this is page should exist, let along have more eyes funneled to it.

Obvious grifter is obvious…

Contain a vacuum in a latex balloon? If you place one balloon inside another, fill it with (e.g.) air, then fill the space around it inside the 2nd balloon with (e.g.) hydrogen, then suck the air from the inner balloon, you just succeed in collapsing the inner balloon and reducing the pressure (and, thus, size) of the outer balloon, serving no useful purpose at all. All it would do is reduce the lift produced by the (dead) weight of the uninflated balloon.

As other commenters have stated, dirigibles with compartmentalized lifting gas have been known for over a century. Even if you want to connect 36 (or is it 54? The description doesn’t match the diagram) spherical balloons to one vehicle, it would be more aerodynamic to connect them in a single row. It would present a smaller cross-section to both the flight direction and cross-winds.

Just a grifter using HaD to spread his bogus gofundme link (for a vaporware online advertising platform), and they fell for it.

Yeah. Also by having multiple concentric envelopes, you have multiplied the weight of the envelope by at least 2x for a single-digit increase in lifting force. Obviously not practical if you bother to think it through even slightly

I am struggling to understand how someone thinks that pulling a vacuum on a balloon will make it buoyant.

I get it, a perfectly empty volume of space weighs less than an equal volume filled with air at STP. There is a Wikipedia page dedicated to the idea of vacuum airships (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vacuum_airship). I think Diamond Age by Neal Stephenson mentions them being used to hold up sky scrapers, though his were super thin diamond shells.

All that being said… shield gas balloons aren’t a bad idea. I have seen concept drawings of H2 envelops inside a pure N2 outer aerodynamic envelope. A direct strike from a .50 cal tracer wouldn’t ignite the H2. A balloon inside balloon setup would let you have a measure of buoyancy control. Increasing outer envelope pressure compresses inner envelop pressure, which shrinks the balloons, and decreases buoyancy. Separating the gondola from the envelops would give one more safety measure if the gas does ignite. It might even let you install some of those massive airplane saving rocket parachutes. If you catch fire, jettison the balloons and pop the chute.

Added complexity means added weight though, and ten smaller balloons are less efficient than one large balloon with equivalent volume.

Vacuum balloons lift like 5-10% more than helium, if you discount any weight increase of the envelope… Which would definitely be more than 5-10%. It’s a cute concept but not really that tempting when you realize the meager gains in exchange for solving an engineering nightmare problem

I used to give my engineering buddies headaches with phrases like, “Take this container and fill it with a vacuum…” Watching them strip a mental gear as they tried to parse that snetence was most pleasing.

You’re right though, the victory of being the person to name vacuum balloons would be a symbolic one at best.

The structural weight to actual lifting gas ratio is way too high. Even if you could make it fly, it would be so much more prohibitively expensive and unnecessarily huge compared to a more optimized envelope.

Why is this on HaD?

This is an obvious scam and/or nonsense. This is only barely more coherent than the free energy stuff.

Airships already have a problem with sectional density. They barely work.

You can’t ‘improve’ them by making the cross section vs lift much MUCH worse.

This idea stops working before you even write it down, let alone start doing any math.

C’mon HaD.

This isn’t ‘Perpetual Motion Weekly ‘.

You can do better.

I believe in you.

Just add Cavorite(tm) !!

Personally I like the Idea of a lightweight foam cube entrapping some heated air.

No fancy gasses, basically an insulated hot air balloon. But unlike a balloon, efficient in it’s energy use.