It’s no exaggeration to say that the development of cheap rechargeable lithium-ion batteries has changed the world. Enabling everything from smartphones to electric cars, their ability to pack an incredible amount of energy into a lightweight package has been absolutely transformative over the last several decades. But like all technologies, there are downsides to consider — specifically, the need for careful monitoring during charging and discharging.

As hardware hackers, we naturally want to harness this technology for our own purposes. But many are uncomfortable about dealing with these high-powered batteries, especially when they’ve been salvaged or come from some otherwise questionable origin. Which is precisely what the Smart Multipurpose Battery Tester from [Open Green Energy] is hoping to address.

Based on community feedback, this latest version of the tester focuses primarily on the convenient 18650 cell — these are easily sourced from old battery packs, and the first step in reusing them in your own projects is determining how much life they still have left. By charging the battery up to the target voltage and then discharging it down to safe minimum, the tester is able to calculate its capacity.

Based on community feedback, this latest version of the tester focuses primarily on the convenient 18650 cell — these are easily sourced from old battery packs, and the first step in reusing them in your own projects is determining how much life they still have left. By charging the battery up to the target voltage and then discharging it down to safe minimum, the tester is able to calculate its capacity.

It can also measure the cell’s internal resistance (IR), which can be a useful metric to compare cell health. Generally speaking, the lower the IR, the better condition the battery is likely to be in. That said, there’s really no magic number you’re looking for — a cell with a high IR could still do useful work in a less demanding application, such as powering a remote sensor.

If you’re not using 18650s, don’t worry. There’s a JST connector on the side of the device where you can connect other types of cells, such as the common “pouch” style batteries.

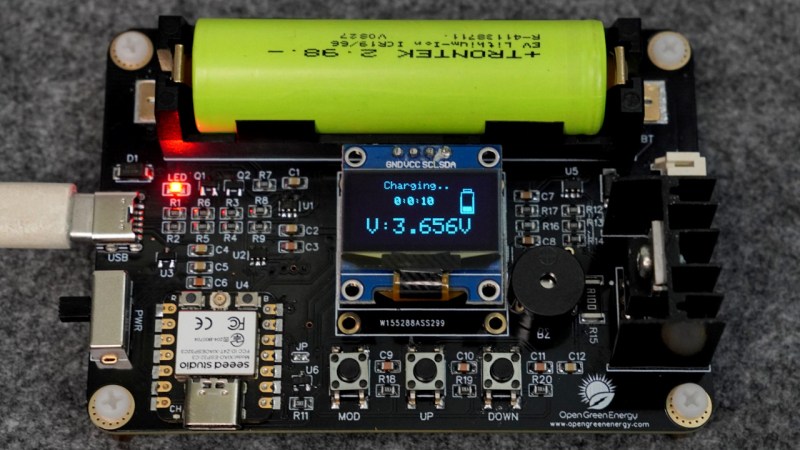

The open source hardware (OSHW) device is controlled by the Seeed Studio XIAO ESP32S3, which has been combined with the LP4060 charger IC and a AP6685 for battery protection. The user interface is implemented on the common 0.96 inch 128X64 OLED, with three buttons for navigation. The documentation and circuit schematics are particularly nice, and even if you’re not looking to build one of these testers yourself, there’s a good chance you could lift the circuit for a particular sub-system for your own purposes.

Of course, testing and charging these cells is only part of the solution. If you want to safely use lithium-ion batteries in your own home-built devices, there’s a few things you’ll need to learn about. Luckily, [Arya Voronova] has been working on a series of posts that covers how hackers can put this incredible technology to work.

All this (rightful) concern over internal resistance and its measurement, but we almost never see a proper 4-wire Kelvin connection to measure it. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Four-terminal_sensing

I know why: It’s because any battery clips or terminals you buy have only the single connection for each terminal.

Has anybody come up with a repeatable, manufacturable Kelvin connection for (say) a 18650 cell?

There are coaxial battery connectors/holders for internal resistance meters (e.g. RC3563 or YR1035+).

They consist of a spring loaded center pin (sense connection) and a spring loaded outer cylinder (force connection).

Examples:

https://www.thanksbuyer.com/image/cache/data/202010/66105/1602033039-2-750×750.jpg

https://i5.walmartimages.com/asr/8e6435d6-20bd-4569-b8ef-0c41c8089116.751f054e7f068d0931c58d102dbdac47.jpeg

Cool. Thanks. Now that looks like something you can whip up janky-style with a couple of retractable ballpoint pen tips.

(And walmart? srsly? )

or add some pogo-pins

+1 for the YR1035, I use it to test cells building packs for small vehicles, where the IR is often milliohms. The thing it gets right is the spring loaded 4 terminal probes and cell holder. Critically important for reliable and repeatable measurements.

how can you connect 4 wires to coax? coax is only 2 wires

Coaxial doesn’t just mean “coaxial cable” – in this context it’s referring to the connector at each side of the battery holder, which has an inner and outer connector.

Tuck thin copper shims between each battery terminal and the power contacts, and clip your voltage probes to the shims? That way you’re measuring the battery potential AT the battery. Resistance across the shim’s thickness should be negligible, assuming it’s clean.

This is great to see and I’m glad to see more OSHW.

However, I do want to point out that this is competing with things like the Opus BT-C3100 which from what I remember is a pretty tried and true choice for this segment.

This is a great step forward though and I’m interested on seeing how they go further to get something that can really beat the competition.

The disadvantage of the opus is that they are hard to repair and when use them extensively they will break. Been trough 20 of them so a repairable alternative is a welcoming gift

these are easily sourced from old battery packs,

Or sourced from the (literally) dozens of vape pens I pick up on the shoulder of the road on my bicycle rides. OK, they’re not 18650, but still .

I do need to measure the the internal resistance of my trash batteries, to keep the good ones for my maker/hacks.

Now just combine it with the Automatic battery charger from the other day. :) https://hackaday.com/2024/12/02/the-automatic-battery-charger-you-never-knew-you-needed/

I know we need to keep dealing with LoPo, but I really want to see hobby/hacker stuff to work with LiFePo4 or even Sodium-ion chemistries become much more commonplace.