In the world of transportation, some technologies may seem to make everything else appear obsolete, whether it concerns airplanes, magnetic levitation or propelling vehicles and craft over a cushion of air. This too seemed to be the case with hovercraft when they exploded onto the scene in the 1950s and 1960s, seemingly providing the ideal solution for both commercial and military applications. Freed from the hindrances of needing a solid surface to travel upon, or a deep enough body of water to rest in, hovercraft gave all the impressions of combining the advantages of aircraft, ships and wheeled vehicles.

Yet even though for decades massive passenger and car-carrying hovercraft roared across busy waterways like the Channel between England & mainland Europe, they would quietly vanish again, along with their main competition in the form of super fast passenger catamarans. Along the English Channel the construction of the Channel Tunnel was a major factor here, along with economical considerations that meant a return to conventional ferries. Yet even though one might think that the age of hovercraft has ended before it ever truly began, the truth may be that hovercraft merely had to find its right niches after a boisterous youth.

An example of this can be found in a recent BBC article, which covers the British Griffon Hoverwork company, which notes more interest in new hovercraft than ever, as well as the continued military interest, and from rescue workers.

Why Hovercraft Were Terrible

Although we often think of hovercraft as something like something modern, they have been something that people have been tinkering around with for hundreds of years, much like airplanes, maglev and so on. These were all rather small-scale, however, and it took until the 20th century for some of the fundamentals to get worked out. The addition of the flexible skirt to contain the air in a so-called momentum curtain to raise the hovercraft further off the ground and add robustness when traveling over less gentle terrain proved fundamental, and within a few decades passenger behemoths were making their way across the English Channel, gently carried on cushions of air:

Yet not all was well. As can be ascertained by the above video, the noise levels were very high, and so was the fuel usage for these large hovercraft. The skirts ended up wearing down much faster than expected, resulting in a need for daily maintenance and replacement of skirt sections. By the 1990s catamaran ferries offered a similar experience as the clunky SR-N4s, while requiring much less maintenance. When the Channel Tunnel opened in 1994, the writing was on the wall for Britain’s passenger hovercraft.

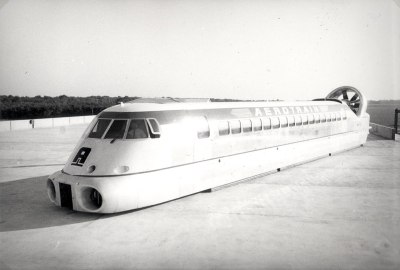

Years before, the high fuel usage and a range of other issues had already ended the dream of hovertrains. These would have done much the same as maglev trains, only without the expensive tracks. Unfortunately these hovertrains uncovered another issue with the air cushion concept. Especially at higher velocities the loss of air from this cushion would increase significantly, while using the environmental air to keep the cushion on pressure becomes harder, not unlike with the air intakes of airplanes.

Ultimately these issues caught up, with the hovertrain’s swansong occurring in the 1970s with the Aérotrain I-80 and UTACV already. The world’s largest commercial hovercraft – the SR.N4 – made its final trip in 2000 when its operator coasted on for a few more years with its catamaran ferries before closing up shop. These days the only way you can see these artefacts from the Age of Hover is in museums, with the GH-2007 Princess Anne SR.N4 as the last remaining example of its kind at the Hovercraft Museum in Lee-on-the-Solent in Hampshire.

Recently the Tim Traveller YouTube channel went over to this museum to have a gander:

Why Hovercraft Are Great

So with that said, obviously hovercraft and its kin were all investigated, prodded & poked and found to be clearly wanting by the 1990s, before the whole idea was binned as clearly daft and bereft of reason. While this might be true for massive passenger hovercraft and hovertrains, the reality for other niches is far less bleak. Especially with the shift from the old-school, inefficient engines to modern-day engines, and more of a need for smaller craft.

Currently passenger hovercraft services are quite limited, with the Japanese city of Oita having a hovercraft service between the city center and the airport. Here hovercraft make sense as they are over twice as fast on the 33 kilometer route as the bus service. These hovercraft are built by British hovercraft company Griffon Hoverwork Ltd., as currently the only company building such craft in the world. Similarly, the Isle of Wight’s Hovertravel is a hovercraft passenger service between the island and the mainland, with two Griffon 12000TD hovercraft providing the fastest possible way for people (including many tourists) to travel. Hovertravel’s services are also chartered on occasion with events.

For these tourism-oriented applications the benefits of hovercraft are clear: they are the fastest way to travel especially across water (74 km/h for the 12000TD) and are rather flexible so that they can be used ad-hoc with events that do not have more than a patch of concrete or grass bordering the water. Noise levels with modern engines and with smaller craft are also significantly more manageable.

As addressed in the earlier referenced BBC article, there are three other niches where hovercraft have found a warm home. These include hobbyists who enjoy racing with small hovercraft, as well as rescuers who benefit from having a way to reach people no matter whether they’re stuck on a frozen pond, in a muddy area, in the middle of a swamp or somewhere else that’s hostile to any wheeled or tracked vehicle, never mind rescuers trying to reach someone by foot. Here the property of a hovercraft of not caring much about what exactly its air cushion is pushing against is incomparable and saves many lives.

To Land Where Nobody Has Landed Before

Naturally, the other niche where a hovercraft’s disregard for things like mud, wet sand and rocks is useful is when you are a (military) force trying to carry lots of people, gear and heavy equipment onshore, without such minor details like finding a friendly harbor getting in the way. Although the US Navy and Army had tried to use hovercraft in a more direct role before, such as the unsuccessful SR.N5-derived PACV in Vietnam, their best role was found to be as landing craft: the Landing Craft Air Cushion, or LCAC.

A total of 97 have been built of these LCACs since their introduction in 1986 and they see continuous use as transport of cargo and personnel from ship to shore, across beaches and so on. Due to increasing (weight) demands they are now slated to be replaced by the Ship-to-Shore Connector (SSC). These are very similar to the LCACs, but offer more capacity (~20 ton more), while offering improvements to the engines, the skirt design and a two-person cockpit with fly-by-wire joystick controls.

Similarly, the Chinese Navy (PLAN) also has an LCAC in service (the Jinsha II-class type 726), and both Russia and Hellenic Navy operate formerly Soviet Zubr-class LCACs, which is the largest currently active hovercraft. A few more Zubrs were constructed by Ukraine for both Greece and China, with the latter also building them under license as the Type 958 LCAC.

Happy Niche

Because physics and economics are relentless, hovercraft, maglev and catamarans never made us bid farewell to wheels, tracks, hulls and simple train tracks, but each of these have found their own happy niches to live in. Meanwhile economics change and so does our understanding of materials, propulsion methods and other factors that are relevant to these technologies as they compete with transportation methods that have been a part of human history for much longer already.

For now at least hovercraft seem to have found a couple of niches where their properties provide benefits that are unmatched, whether it’s in simply being the fastest way to move over water, mud and concrete all in one trip, or for the most fun to be had while racing over such a track, or for providing life-saving aid, or to carry heavy loads from ship-to-shore when said shore is muddy marshes, a beach or similar.

Even if we will never see the likes of the Princess Anne again crossing the Channel, the hovercraft is definitely here to stay.

Mine is full of eels, as is traditional.

Mine is named the ‘Full of eels’ but is not in fact, full.

I always wanted that Tyco RC hovercraft toy when I was a kid.

I still have the one I got new in the 80s when they came out. It was really cool in its time!

My dad had one but the desert here had turned the skirt to dust. I was 8 when that happend and my pops said i could have it. I must have tried a million different homemade solutions to the skirt problem. From trash bags to bike tubes, nothing semed to get it to more than a slow crawl. I think it eventually sunk in the pool after i gave up and tried to make a swamp boat. Should have used something other than hot glue afir that one because the soda bottle pontoons didn’t hold and the styrofoam that was supposed to protect it from sinking had suffired the same fate as the skirt.

My little brother had one, and while it was fun (and loud!), being toy sized, it couldn’t really travel over grass, and our pond was only about 2m across at the widest point, which it would cross in about one second. This meant the only place we could play with it was in the house (carpet was ok, tiles/lino was better), but it was so loud our parents swiftly got annoyed with it.

My friend had one and it chewed through batteries like crazy, and the Ni-Cd rechargeables at the time were expensive and no0t very power dense. I think the hovercraft used 8x AAs… so the 12V nominal battery pack would only be 10V with freshly charged Ni-Cds. Another toy that looked cool, but couldn’t quite deliver with the consumer technology of the time.

Today’s kids don’t know how lucky they are. for example, R/C electric helicopters were an impossible dream in the 80s, and now they are so cheap they are almost disposable. Of course it’s not just batteries, the motors are better, big FETs are cheaper to drive them, solid-state gyros are cheap and the software to run it all is widely available. Maybe it’s time for a reboot of that hovercraft…

And don’t forget the new propeller designs!

There’s a few beaches in the west coast of the UK where there’s a lot of boggy mud/sand when the tide goes out. Wheeled/tracked vehicles can’t cross it, and boats can’t go through it, so the rescue services use hovercraft to rescue people that might get stuck. One example from last year: https://www.somersetlive.co.uk/news/local-news/new-emergency-hovercraft-used-somerset-8185105

I did the FranceUK crossing on a hovercraft as a kid, was horrendously sick on the way back, but not sure that was the crafts fault.

Morecambe bay is also a huge area of mud and quicksand when the tide is out.

There’s been a Royal National Lifeboat Institution hovercraft operating here for more than 20 years

https://rnli.org/news-and-media/2022/november/28/morecambe-rnli-celebrate-20-years-of-its-inshore-rescue-hovercraft

There’s plenty of rescue departments that use them where it snows to rescue people that fell through ice because of their low ground pressure

The fire department two departments over from mine has a hovercraft for marsh rescues. They have a marshy area near the docks in that district, so a boat isn’t always enough for water rescues.

As noted in a recent HaD article, a small-scale version of this technology is widely used to move heavy objects around smooth-floored warehouses. It seems like a fundamentally good technology that’s mainly held back by the practical difficulty of the skirt. (And possibly the failure mode when moving at speed; I’ve never seen it discussed but I assume the hovercraft equivalent of a tire blowout would be bad).

Interesting article- I actually live less than a 30 minute walk away from the IoW hovercraft which, to my knowledge, is the only commercially ran hovercraft service in the world. I didn’t actually realise that was the case until my late teens, so I spent most of my childhood just assuming hovercrafts were a standard form of transport! (Not that I’ve been on it in a good decade or so)

Same – I grew up in the Portsmouth area and so I suppose the existence of hovercraft as this kind of ferry option is something that I always assumed.

I’d suspect you’d need a really really crazy rapid and complete failure of the skirt in a way that is functionally approaching impossible to actually harm craft – as hovercraft without skirts have been done before, and plenty of hovercraft racing ends up with damage, that doesn’t stop ’em.

Really the skirt just makes it easier to maintain that pressure differential to the atmosphere only where you need it – a few holes in it, even quite big ones won’t do anything much but hurt the fuel efficiency as unlike a tyre blowout where you have gone from 30psi to zero rapidly with no recovery path here you are going from 3psi down to 2.5psi till you crank up the lift engine/divert more thrust. (Remember a hovercraft has in tyre terms a contact patch as large as the skirt diameter so the pressure needed to support the weight of the vehicle is really low).

Wheels and hulls require no energy expenditure, they just work. And they have predictable failure modes. Failure modes assisted by the above fact that they don’t require anything beyond their mere matter to keep working. That has basically always guaranteed that having two vehicles (a wheeled and a boat) is preferable to have one do-anything-poorly vehicle. Except in extreme edge cases, like when the Navy needs to storm a beach in a hurry. Even then, it’s iffy.

Agreed. Wheels and hulls also provide resistance to deflection by crosswinds. Hovercraft have to expend thrust to correct for lateral movement, and that’s thrust that’s not moving them forward.

I enjoy a hovercraft myself — I rode an SR.N4 from Dover to Calais and back in ’86, and always thought it would be fun to build a personal one. (Maybe with the grandkids, one of these days…) But they definitely have their tradeoffs.

equivalent of a tire blowout would be moving over a (large enough) grill

The ProjectAir YouTube channel just made a mini, jet-propelled hover train that uses momentum curtains in a video that dropped yesterday! It actually inspired me to start designing a momentum curtain hover craft where the pads are long but the width of railway rails to make an abandoned railway exploration craft!

Wow that G.I. JOE “KILLER W.H.A.L.E.” inspired illustration took me right back to 1984.

I remember a very rough channel crossing by hovercraft when I was a kid 🤮

The IoW one was better.

The BBC Planey Earth team used them on one of their filming trips, to cross salt plains filming flamingos. They underestimated how abrasive the salt would be, and a local tribe – who’d never seen an hovercraft before in their lives – are now probably the world experts on repairing hovercraft skirts. It’s all in an excellent behind-the-scenes section.

Hear me out: Hovercraft monorail. It could work. It would be really cool… and MONORAIL!

If I can actually think of a use case for something like that, does it ruin the joke… or make it better?

not something that tries to do both simultaneously, mind you, but I could see a hovercraft with an attachment to connect to a rail for crossing difficult terrain. Say you had an otherwise hovercraft-friendly route that included a steep mountain, valley, or.. i dunno, a river full of hovercraft-skirt-eating piranhas.

I hear those things are awfully loud.

It glides as softly as a cloud

What? Speak up – I can’t hear you over all the noise!

Air hockey table.

I seem to recall seeing ads to buy plans to build your own hovercraft in the back of magazines.

Had no idea that car-carrying hovercrafts existed. That’s wild!

Modern version runs on leaf blower, old school used vacuum cleaner blower.

Actually worked, not like the comic book submarine.

“…not like the comic book submarine.”

The trick is not to install the optional screen door.

[Christopher Cockerell] who invented the first practical hovercraft (with a skirt to keep the air in), built his first prototype out of his wife’s vacuum cleaner.

There are a number of websites devoted to pedal powered hovercraft (although pedal hydrofoils are much faster and more efficient.) But one, called steamboat willie (there’s a webpage for it somewhere) was particularly well designed and capable of some pretty significant distances.

Hesitate to comment here because it may be more suited to the Dull Mens page but…….

My father who was a pre Boomer and left school at age 13 (just after WW2) was a farm worker all of his life in England. One of his passions was duck shooting on the local river (Stour in Essex/Suffolk). Unfortunately, taking a boat up or down the river was a nuisance because of the number of weirs on the river for flood control. He came up with the idea of using a hovercraft and sliding up the river bank when he came to a weir and hence getting past the weir.

So began the hovercraft build. Comprising of an engine from a Renault (Aluminium because it was light), the starter button from a Bedford Van (because he happened to have one), a very expensive propeller plus before all of this a huge amount of research – including how to weld aluminium 101.

He did finish it and it worked very well – providing you were a small and very light child…..

I don’t know if this classes as a heroic fail however I will assert that his actions bless him, make him a supremely qualified early hacker.

Given the implied age of this construction, and educational background actually being that successful first time out seems really impressive to me – I’d hope in the age of the internet getting the power/weight ratio right and having access to better lifting fan geometry you can order (or make with the CNC) getting at least closer to lifting the adult first time out would be possible… Heck now you can just look at the hovercraft racers webpages to see what they are using for lift motors for a good baseline to copy from, learn how to fibreglass over Al honeycomb (for really stiff and light structure with a technique something that was probably almost unheard of to most folks in the era I’m thinking) etc.

Without them we would have missed some of the best of Jackie Chan’s antics.

They are also used for icebreaking in Canada. The vibration and speed are enough to quickly break up relatively thin ice, such as on rivers and bays.

In 1963 I built a hovercraft for my 8th grade science project. Octagonal, about 2 feet across, balsa wood and a glow plug engine. I think it managed about a half inch elevation. I tested it over pavement and water, and got some cuts when the blade grazed my hand.

They are used for traveling to islands over ice in Finland. A lot of people have houses or are building on the islands and the waters to the individual islands aren’t icebroken.

Before it was the hovercraft museum it was HMS Daedalus, my journey home from school in the back seat of my mum’s car was interrupted more than once by the lights flashing, the gates opening, and a military hovercraft drifting out of the gates, across the road, and down the slipway into the Solent.

They also did other amphibious vehicle exercises from there, and there was an air show for a while – I remember Concorde and the Red Arrows buzzing our house.

The museum is well worth a visit – it’s delightfully eccentric.