We were surprised when we read a post from C++ creator [Bjarne Stroustrup] that reminded us that C++ is 45 years old. His premise is that C++ is robust and flexible and by following some key precepts, you can avoid problems.

We don’t disagree, but C++ is much like its progenitor, C, in that it doesn’t really force you to color inside the lines. We like that, though. But it does mean that people will go off and do things the way they want to do it, for any of a number of good and bad reasons.

We will admit it. We are probably some of the worst offenders. It often seems like we use C++ the way we learned it several decades ago and don’t readily adopt new features like auto variables and overly fancy containers and templates.

He proposes guidelines, including the sensible “Don’t subscript pointers.” Yet, we are pretty sure we will, eventually. Even if you are going to, also, it is still worth a read to see what you ought to be doing. We were hoping for more predictions in the section entitled “The Future.” Unfortunately — unlike Hackaday authors — he is much too smart to fall for that trap, so that section is pretty short. He does talk about some of the directions for the ISO standards committee, though.

We should have known about the 45 years, as we covered the 30th birthday. We like safer code, but we disagree with the idea that C++ is unsafe at any speed.

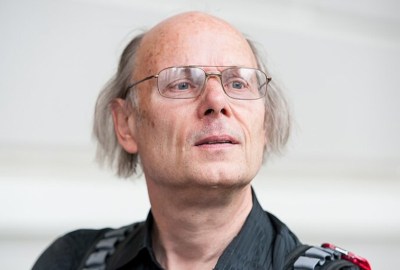

Photograph by [Victor Azvyalov] CC-BY-SA-2.0.

Obligatory Stroustrup interview link:

https://www.ganssle.com/tem/tem17.htm

Reading just the first few paragraphs from the post that is the subject of this article, that older “interview” seems plausible.

If after so many years we still don’t get it, this can only mean the design of the language was not good thus he is the one who doesn’t get it.

No need to be petty, good people sometimes do bad things.

“We are probably some of the worst offenders. It often seems like we use C++ the way we learned it several decades ago and don’t readily adopt new features like auto variables and overly fancy containers and templates.” .. probably its the best to skip C++ and go directly to RUST ;-)

Or skip Rust and wait for the next one, it seems a trend that new programming languages are invented continuously. And none of them really fix the real problem: sloppy programmers and bad quality assurance (programming practices, code review, testing ..).

And maybe skip programming altogether and wait for few years as most of programming is done by prompting AI.

New languages come and go, but C and C++ seem to stay ..

Just learn Rust. It’s designed specifically to fix those.

Except much of the Rust libraries needed to build real applications is not memory safe. And not data race safe.

Yesterday I learned that there is a funded effort to formely verify the rust libraries and provide the tools for other code.

That’s objectively untrue.

How is rust better then ADA?

I’ve yet to hear a reasoned answer to your question. Unless you enjoy coding in hieroglyphics then Ada is clearly better. But happy to hear reasoned explanations why it’s not.

yes. By a large margin…

UTF-8, for one random thing ADA may never be able to fully support, realistically.

Sorry, gotta say it: ADA is the American Dental Association. The programming language is Ada, after Ada Lovelace.

How about. I stead of inventing better programming languages, we develop better programmers?

I’ve been in the business over 30 years, and the quality of course code is abysmal. And it’s getting worse.

Requirements suck. No meaningful design is done. Basic best practices are ignores or unheard of. Code reviews are a rubber-stamp process. Mentoring is unheard of and even if it were a thing, the guys who DO know better are retiring.

Model-driven development only serves to further insulate the author from the problem, should one occur. Debugging model-based code can be like playing the piano with mittens on.

Put your big-boy pants on and get the basics RIGHT before trotting off to the next shiny new toy that promises to solve all hour problems, most of which aren’t even related to the language.

You don’t need a steel axe, you just need to be better at using your stone one.

Course code is abysmal because curriculum code is written on the cheap by Indian undergrads with (now with LLMs, yay). This is literally the case for the bar majority of teaching materials now that Venture firms have pushed compensation prices down.

Reminds me of when Java was supposed to be a panacea with its garbage collector.

rust is absolutely trash that aint stable enough even for linux kernel. rust is used by teenagers trying to be edgy and not a single big serious software company uses it

microsoft, cloudflare, mozilla, google laughing at you

No really, you most likely are running Rust code everyday if you have anything running Android, Windows, or any modern Linux distro. Lots of backend code for critical services are now using Rust apps at Cloudflare also, a bunch of automotive companies have ECUs running Rust code.

Don’t feed the trolls, especially when they’re as blatant as this one.

Literally everything one can do in rust can be done in standard c++. Otherwise not.

Why stop there? Use FPGAs.

The FinTech mob encode business trading rules in hardware, since the odd millisecond latency is worth a lot of money.

They lay transatlantic comms cables for their sole use, and buy up microwave telecoms links between Chicago and New York because the speed of light in air is higher than that in glass.

Yes, it’s Turing-complete. You can get it to do anything. The point is not to ask “what can you do?” but instead “what can you not do?”. From a safety and security perspective, the latter question is much more relevant.

Spot on.

Amateurs think about how things work.

Professional think about how things fail.

Addition to your statement: what don’t you have to do (because it is guaranteed by design)

at this point learning a new programming language is probibly a lot easier than learning all the new stuff c++ has.

Tried C++ a long time ago, and it’s even more complicated now. Instead, I use object-oriented programming principles in C. It’s funny that every new programming language gets written in C, then eventually gets ported to itself. C is no more and no less than the lowest-level language that is portable across dramatically diverse machine architectures. The rest is just about people trying to avoid self-discipline.

Never forget that there are valid and conforming C++ programs that can never be compiled, because compilation takes an infinite time. The C++ designers refused to understand and recognise that until Erwin Unruh rubbed their faces in a program 30 years ago.

Unruh created a (valid, conforming) C++ program that causes the compiler to generate the sequence of prime numbers during compilation. Since that sequence is infinite, compilation can never finish.

For the avoidance of doubt, C++ compilers may have an arbitrary internal limit on recursion depth, and exceeding that causes the compiler to give up in disgust. That means that C++ compiler cannot compile a valid conforming program.

The code,and explanations, can easily be found by searching.

Corollary: if the C++ designers don’t understand what they have created, what chance do mere mortals have of understanding?

If you don’t/can’t understand your tool, what is the probability that your code contains unrecognised errors.

No, unit testing cannot find such errors. If you think it can, then please supply a unit test that proves a transaction has ACID properties :)

Corollary: If someone is doing Template Metaprogramming, they need psychiatric help. Or 1000 hours of community service – debugging Template Metaprogramming. :-)

Really I admire the hack, but people… PLEASE do not let that stuff escape into the wild.

This is not unique to C++ – any language could have a similar problem with a program constructed to be undecidedable.

Which language(s) do have the problem with valid conforming programs?

Did those languages designers also refuse to believe the problem until someone rubbed their noses in it so they couldn’t deny it any longer?

The template system is Turing complete, so yes you have a Turing machine available to you at compile time, and yes that means you can implement infinite loops. It’s that simple. Any sufficiently complex system will exhibit this behavior. I haven’t seen it demonstrated, but I’d bet this week’s paycheck the C preprocessor could be made to do the same.

Template meta programming is a neat trick, but it’s going to get noticed in code review. It’s not going to escape into the wild accidentally. Either you have a really good reason for doing it and everyone understands that, or you are going to be rightly smacked upside the head for trying to commit it.

It’s also not a big deal. Any real compilation pipeline is going to have a timeout built in somewhere, or at worst an impatient human that will eventually mash ctrl-C and figure out what the heck is going on. An infinite loop in compilation is basically as good as a syntax error.

How can the C preprocessor be turing complete if it doesn’t have loops?

Turing completeness doesn’t require “loops”, it requires the ability to execute its program as its program requires. In this case probably by recursion, but you can make up your own imaginary Turing machine with its own weird but technically Turing complete language. Many other people have done so, I had an interesting example used as part of an interview several years ago.

This is such a strange issue to take – many “valid conforming programs” never terminate. Sure, it would be nice to get a compiler warning I suppose but your problem seems to be that the C++ compiler doesn’t solve the halting problem (which is not really what it’s there for…)

I think you’re misunderstanding the problem.

It’s not that the output program doesn’t terminate.

It’s that the COMPILER doesn’t terminate, or it does, but it fails to produce output.

This means that there is a program source that is perfectly well-formed, and fully complicit with the C++ standard, that can never actually be fully compiled by any existing (or even theoretical) compiler.

I don’t think it’s a “strange issue” to think it weird that the C++ standard, as written, allows a scenario where a well-formed standards complying program can’t actually be compiled by any compiler. Such a program either shouldn’t break the compiler, or should somehow be violating the standards.

And yes, that is basically (as you put it) asking the compiler to “solve the halting problem”, but the issue is that the standard is written in a way that it’s even susceptible to the halting problem in the first place.

It is a non-issue. Timeouts and better errors would be nice but this is not what makes it a bad language.

This is a non-issue. Making a type system accidentally Turing-complete doesn’t make it any less useful or correct. In fact, it’s pretty much a requirement if you want to implement a lot of desirable features.

Rust also has a Turing-complete type system. It is a non-issue.

What isn’t a non-issue is C++’s utterly unprincipled and snake-oil attitude toward safety.

Just so, but also…

It is a good simple eye-opening example of the stupid/dangerous/incomprehensible complexity of C++.

“Incomprehensible” is correct, because the C++ experts designing the language could not and would not believe it.

Not a C++ guru, but I heard there is still no buffer overfow detection implemented inside the compilers… /s

There is no bounds checking for array indices, but there are other containers like std::vector that do.

So? Learn to program correctly. Yes bounds checking exists on certain things today because people don’t know how to code. However this just slows things down and take up more space. If I allocate 10 bytes and I know that I only store 10 bytes and only ever read 10 bytes I don’t need some artificially constructed container because I am not a baby. An artificially constructed container is going to check every read and every write, a process that will take many instructions cycles, it is going to need to store a length somewhere taking up more space (probably 4 bytes), all to hold the hand of someone who should program in a language that is more hand holding. I am horrified by the complexity of ‘modern’ C++, it seems to include every idea from everything else ever invented instead of just letting people learn to be adults. This is the problem not just in C++ but in every piece of modern life.

You obviously haven’t been asked to do print 1 to 10 with a lambda in an interview. A lot of us make a living writing overly-complex C++.

To print numbers from 1 to 10 using a lambda in C++, you can encapsulate a loop within the lambda itself. Here’s a concise example:

#include <iostream> int main() { []() { for (int i = 1; i <= 10; ++i) std::cout << i << " "; }(); // The lambda is immediately invoked }Explanation:

– The lambda

[]() { ... }contains a loop that iterates from 1 to 10.–

iis declared inside the lambda and increments each iteration.– The lambda is immediately executed

()after definition, printing the numbers.Alternative using

std::for_eachwith a container:#include <iostream> #include <vector> #include <algorithm> #include <numeric> int main() { std::vector<int> nums(10); std::iota(nums.begin(), nums.end(), 1); // Fill with 1-10 std::for_each(nums.begin(), nums.end(), [](int n) { std::cout << n << " "; }); }Explanation:

–

std::iotafills the vector with numbers 1 to 10.–

std::for_eachapplies the lambda to each element, printing it.Both approaches achieve the goal using a lambda, with the first being the most direct.

I spent many years dealing with security bugs in products. A very large number of those bugs were introduced by people who sounded just like you.

Can’t recommend hire.

So, what you are saying is that is impossible to determine if the size of the container you need for that part of your code is ten and only ten bytes, so better allocate 10 or 100MB, because who knows…?

I’ll hire the programmer who understands what is doing, instead of the paranoid one who write his code trying to avoid God knows what.

The arrogance is astounding. It’s called being human. Humans make mistakes. Constantly. And you talking like you never do is either an obvious lie or proof of inexperience. Or are all your applications less than 100 lines long?

When a program reaches sufficient complexity it can eventually no longer be held in one’s foreground memory without considerable cognitive load, at which point we end up with security exploits.

The grand majority of bugs and security holes are created when programmers say to themselves “that’ll never happen…” (or are too lazy/hurried/inexperienced to know or look up what can happen).

And there is your first bug: the length will potentially (likely?) be eight bytes (64 bits).

Sorry, had to do it. I’ve graded too many assignments to let that one get by. Done it myself a few times, it’s cool. :-) :-)

Anyway, if you really, really need to use C/C++ that way, you probably need to use machine language instead. Admittedly, x86_64’s 4000+ opcodes poses a challenge these days, but if you’re charging by the hour you’re golden.

Seriously, Intel – Gaussian Field instructions? Who on God’s Green Earth did you put that in there for? Never mind, I know who.

Aren’t you confusing Gaussian with Galois?

And GF instructions are quite common – even relatively old fixed point C64+ DSPs have it.

What you are describing is premature optimization.

People make mistakes, especially when you have someone that didn’t write the code changing it five years down the line with an angry customer or project manager breathing down their necks. You have zero control over who will change a code base next. It’s ALWAYS best to code defensively.

If you have an identified performance issue or hot spot in the code, then and only then does it make sense to “remove the brakes to save weight” so to speak. Those situations do occur, and you carefully comment them, spend more time analyzing them, increase test density, etc.

99.9% of code doesn’t run under conditions where those extra CPU cycles matter. Even in modern embedded systems you rarely have a processor that is near 100% utilization most of the time.

Optimizing to save every last CPU cycle by default is, frankly, a mark of immaturity. Part of being a professional developer is understanding when that behavior is necessary, and showing the discipline to mitigate risk when it is not.

And whil I whole heartedly agree, it’s the opposite that is happening. Ever more bloat and software being slower then it ever was …

Bloat is certainly a growing problem. I’d argue that this is not being caused primarily by lack of micro optimizations though. The bigger culprit is the proliferation of ever more layers of libraries, poor choice of algorithms that results in poor scaling, and ever growing amounts of telemetry.

I’d complain about the rise of LLM’s and their insertion into every application we touch, but that doesn’t even feel sporting.

Barry: bloat is literally a growing problem.

I am working fulltime with c++ but have an embedded c background. If you are using c++20, sonarlint, clang tidy, wall, werror, etc, you will be fine :) using modern c++ you can avoid using pointers and direct accessing elements by index and other error prone practices. The c++ i write today is not the same language i learned 10 years ago. Regarding Rust, i would prefere a standard and more then one compiler, i doubt rust code written today will work in 5 years.

This!

Todays C++ is just as modern as Rust and have all the needed features to make memory safe and quality software with C++.

And you don’t even need to try hard..

Not even close. Safe Rust makes data races impossible.

And the moment you need to deal with real world, the safety goes out of the window because the OS libraries aren’t safe. Plus never mind that data races are only one type of problem – and not even the worst one you could encounter.

This superiority complex of Rust developers while being totally blind to very real problems that don’t go away only because one has switched languages is incredibly tiring already.

I love how you mention OS libraries aren’t safe, but one favour, remind us what language are they written in again?

I’m a fan of modern C++ and safety is definitely improved but no, it doesn’t have the memory safety of rust. In rust memory bugs can only occur inside unsafe blocks; it’s literally impossible for a conformant compiler to generate code that uses after freeing, double freeing, etc outside of unsafe blocks. It’s harder to write memory bugs in modern C++ than in premodern C++ but it’s still possible pretty much anywhere. To be able to say “I know 100% that these units (or this entire program!) are 100 % memory safe” is a powerful guarantee that C++ can’t give you.

Rust from 2015 still compiles. I already have Rust code more than 5 years old.

And all those things add heaps more instructions and storage to your program, just so people can be lazy and not check or learn. It’s not as if the tools to help don’t exist today. Pointers and direct access are how the processor deals with memory, anything else is hundreds of extra it’s of code,just because it is hidden behind a name doesn’t mean it isn’t extra

We are also fallible humans. People don’t have to be just lazy or ignorant.

Human coders are fallible, and those faults include laziness. Unless they’re replaced by infallible AI (which seems highly unlikely), the languages they use need to accommodate reality. When critical software fails, or is compromised, saying “they were lazy!”, might feel good, but it doesn’t fix anything.

At some point, maybe it will the AI’s on here arguing their superior methods of generating code.

Will AIs arguing on message boards get into an infinite loop of one-upmanship just like humans do?

LLMs are trained on code produced by fallible/lazy programmers.

LLMs produce output which is (probably) syntactically correct. Whether it is semantically correct is a different issue.

It’s hundreds of extra instructions, not hundreds of extra “lines of code”. Those are two very different things.

The former is usually being generated by well tested and mature container libraries that have thousands of people using them.

The latter is usually unique to a single product, application, or domain specific library with far fewer eyeballs on it. Every line of code is an opportunity for you (or more likely the intern that gets assigned to make a “trivial” change two years from now) to make a mistake. They carry very different levels of risk.

The extra instructions do represent increased memory and CPU usage, and those are at times scarce resources. Usually though a CPU spends the vast majority of its time in a tiny percentage of the codebase. Most lines of source code are there to handle errors, rare edge cases, and initialization that might occur once or twice during the execution of the program. Most real world applications tend to be I/O bound as well.

The tradeoff between performance and risk is not uniform across a codebase, and the places where “performance” is the more important consideration are the exception, not the rule.

“We are probably some of the worst offenders. It often seems like we use C++ the way we learned it several decades ago and don’t readily adopt new features like auto variables and overly fancy containers and templates.” thus makes me feel so much better. Often times new languages come in with new features and so much, but the C++ today is barely how I remember it. I ha e nothing against new languages but it doesn’t give me the power I have with c++, the nice feelings. Every other one makes me feel like I’ve reached into a new domain. But c++ always left me in wonder.

To be honest, lot of us doesn’t want to get it and we don’t have to get it. We need only some advanced features over C like namespace or minimalist objects which have minimal to zero runtime/size overhead compared to C code.

The problem with C++ is the legacy stuff that should never be used is enormous. Then there’s the endless list of weird features that should only be used in rare conditions. C++ needs guardrails and a reduced syntax. Rust provides that.

Sutter’s Cpp2 is an attempt at that, but I’m not holding my breath about it ever becoming mainstream.

Rust has the same problem in that it’s also evolving and growing, and at a much faster pace than C++ ever could since there’s no ISO committee to drag things down. The editions are supposed to mitigate that somewhat, but you still have the same problem of having to unlearn old practices, and encountering legacy code.

heh i basically came here to say this, but not to recommend rust!

i’ve designed my own language a couple times and usually i get to the point where i realize some early choices now look like mistakes, but have forced me into dealing with a bunch of special cases or accepting slowness or so on. and it gives me new respect for things like scheme or early java or ML where the language really truly is simple and the early choices were carefully made (or repeatedly refined before publication) until they didn’t force you down any painful paths.

C++ is all bad choices on top of bad choices. every new standard revision since C++11 they start with the premise that the old choices didn’t deliver the generality that they had promised, and that they need a new set of idioms…unfortunately, they don’t throw out the old idioms. C++ is designed in such a way that every detail affects every other detail so it’s full of special cases. templates, inheritance, exceptions, namespaces, they all feed into eachother…none of them is properly abstracted. a real nightmare for compiler and runtime implementations.

like, C++ has from the beginning had an ambiguous question, do compilers parse templates as generics, or do they treat them like macros, only actually parsing the contents once the types are known? what happens for errors in a template, does the template just ‘disappear’ and fall back to something else, or does it generate a compile time failure even though there’s a valid definition that would work? these questions are pretty well decided since C++11 but they were left open for a couple decades causing no end of trouble, and the echoes of that trouble still exist in the latest language

i agree rust is going in a better direction. maybe it’s just coincidence but the first time i used rust i ran into two quintessentially C++ problems. first is that the language is evolving so quickly that code from yesterday never compiles. the rust fans are quick to point out “that’s only because they used ___ feature that they shouldn’t have used” which is just the same problem with C++! and the other problem was that the first ‘generic’ code i met — a wrapper library from rust to C — wound up copy-pasting an idiom a dozen times, once for each type that it needed to accept. i don’t know if they truly failed — again — to build a decently generic type system or if they provided a great set of features that in practice programmers just don’t know how to use???? either way, it felt a lot like C++ in actual real life practice.

A lot of programmers who learned the syntax of C++ skipped learning how to do object oriented design and programming let alone nee C++ features.

I wish I could find my old presentation I used to give for a NASA contractor back in the 1990s called “12 words to object oriented programming.” It was to combat exactly what you are talking about.

I’d probably read that.

Cpp was a mistake in 1990, 2005 and it’s still a mistake in 2025.

At work I use a MISRA-like subset of C that’s super limited in terms of features but it get the job done just as good as C++, Java or C# would do, except it doesn’t leak memory or waste CPU cycles.

If C++ is the answer, then you need to go back and re-assess the question. :(

Sure, the (other) people commenting here might[1] write perfect code, but what about all the libraries that they use?

[1] remember the C++ committee who didn’t understand what they had wrought!

I describe MISRA as “the parts of C that are also in FORTRAN 66”. I mean that as a compliment. If it isn’t true, it’s mighty close.

“You can write Fortran in any language.’

Ah, but can you write every other language in Fortran? (The answer is yes: DEC for a while used Fortran as their systems programming language.)

C++ can be a better C. You can do a lot of useful things at compile time. You can generate a sine lookup table or convert a base64 string to a const byte array at compile time.

I usually write a program to generate my constant tables.

c++ software obfuscation?

Is c++ implemented with certified software modules?

AI Overview

“Certified software” refers to software that has been independently evaluated

and verified by a recognized organization to meet specific quality standards,

often related to security, functionality, performance, or reliability,

signifying that it has passed rigorous testing and meets certain criteria

for its intended use; essentially, it’s a label indicating a level of assurance

regarding the software’s capabilities and compliance with industry standards.

Bjarne? Bjarne? If you don’t want people to subscript pointers, then why is that in your language, Bjarne?

Probably since there are times you need to. That is the beauty of c/c++ . The do anything language, where you are not bound by the language. Your free to do anything. Wonderful. Unlike Rust, where the ‘compiler’ kicks back at every turn even to point of how you format your code statements…. embedded/real-time C programmer since ’85, with some C++ over the years. And Turbo/Delpi Pascal as well. C with ‘some/basic’ Oop works well. Using the obscure features of C++ sucks for maintainers down the road though. KISS. Experienced this as a maintainer of a previous engineer. No fun to figure out what is going on when you have to dig to make a change.

Here is too another 45 years!

Subscripting pointers is possible because it was easy to do on a PDP11. See K&R first edition.

I like it when a compiler complains at compile time – because that prevents some avoidable problems occurring at runtime 3 years after the perpetrator left the company. No, it doesn’t prevent all problems, but it reduces frequency with which they occur.

Here’s to another 45 years of COBOL!

(Damn; escaped too soon)

“because” is because it was easy for the compiler to do, and because the PDP11’s instruction set implemented it efficiently.

Fundamentally, it is a “leg of lamb”/”pot roast” feature https://www.psychologytoday.com/au/blog/thinking-makes-it-so/201402/the-pot-roast-principle

It’s in the language because Bjarne wanted seamless C interop and it’s a thing in C. The smart pointers in the standard library don’t have subscript or arithmetic operators.

I have used C++ forever. I have not adopted some new styles because I have an existing code base of tools. I think the problem with committee design is the introduction of regressions in existing code, they simply do not back-test when they deprecate or change things.

It seems to me the reason some of us still use C++ like “C with optional objects” is because that’s how it started out. The first two versions of “cfront”, the original C++ compiler, didn’t emit assembly code, they emitted C, which was them compiled to assembly and assembled. Thus, all the semantics of early C++ have a 1:1 mapping to a fragment of C. There’s is no reason in the world for me to know that a “vtable” exists, what it does, or why it’s there. The problem is, I DO know. I HAD to know, because the debuggers didn’t catch up to the language for nearly a freakin’ decade. And I’ll just throw this out there: Name Mangling. You’re welcome.

Remember the treadworn advice “don’t use templates, they’ll break the debugger!”? Break the daylights out of it. Wound up having to put a printf() everywhere (sorry, “cout”) just so you could tell which method (sorry, “member function”) you were in.

Lately I’ve been writing Erlang at work. If you don’t like C++, Erlang is as different as conceivably possible. When I stand up after a while, I have to try to remember where I am.

“It seems to me the reason some of us still use C++ like “C with optional objects…”

The way it ‘SHOULD’ be. There is absolutely no reason to use objects just because. You should have a very ‘good’ reason to do so. Use where it makes sense. Even in python, I won’t create ‘objects’ — just because the construct is available. Code is usually much cleaner this way, rather than hiding the code behind objects for no reason. Don’t get me wrong. Sometimes objects make sense to use. Just don’t use them for the heck of it. One of biggest ‘headaches’ at work is a previous engineer using c++, objectized everything because he could and used overrides on operators. Ugggh. So tracing down the code (object) chain, you’d forget what you were looking for by the time you reached bottom and have to start over again. Very obtuse. After addressing what you are looking for, a couple months go by and guess what… Have to do it all over again…

Always disliked the name mangling too when debugging. One of the reasons I still prefer to write in straight ‘C’. Simple and straight forward coding. Easy to follow the assembly in the debugger.

Name mangling is ugly, an indication that the tool is becoming part of the problem rather than part of the solution.

Operator overloading makes some simple things pretty. When (mis)used on more complex things, it rapidly makes them incomprehensible.

Another example of C++ including things because they appear k3wl, not because they are beneficial.

Did COBOL fall into that trap?

“The way it ‘SHOULD’ be.” preach it!! i go ahead and use C idioms in java too. the ‘design patterns’ that people use with java are absurd, when they’re so often just trying to make straightforward imperative sequential code like C. if you need a zillion copies of the object then by all means use a constructor, or admit you don’t like the language support for OOP and use some sort of factory / interface idiom. but i’ve seen so many pointless wrappers and boilerplate when really you’re just doing the simple thing. you could do it the simple way!!

java has a ‘static’ keyword. it really is capable of all of the basic C idioms we already know. same for C++. even ocaml lets you resort to doing simple things the simple way. use it and just keep an eye out for when it bites you so you can at least learn from the experience :)

I never liked C++, the standard template library was always no more than a bag on the side. While I had to use C itself for a couple of decades, for the last few years of my career I ended up using C# which was so much better than C++ in all ways – no multiple inheritance, generic classes that were type safe even with user defined classes by the use of interfaces, etc. Rust wasn’t even a gleam in the designer’s eye but I suspect it is superior to C++ in every conceivable way. Languages come and languages go, but C++ has proved to be generally write only code that never deserved any prominence in the first place.

Of course, that is just my opinion, but had C++ been a necessity I would simply have found a new job – maintaining other people’s C++ was more than enough for me, it was a relief to retire and leave that chore to others.

Problem I had was C# is a M$ .net centric (with all its baggage) language. Not built for cross platform like Java or even c/c++. I only wrote one application with C# and truthfully, I didn’t mind it at all. Easy to use. Just didn’t fit with the projects I work(ed) on so never went any further. Yes you can write some C# on Linux now if needed although GUIs are (or were) limiting, but between C/C++, Pascal, Java, Assembly, and Python … I’ve got a mind full of syntax to keep track of! You don’t find C# on micro controllers, RPIs, etc. either. I’ve got a friend in IT which loves it. But he gets frustrated when trying to use it for home hobby projects and usually ends up with Python as the goto language which he is finding is a better fit.

ugh “other people’s C++”. you wind up seeing hack-upon-hack where the big question you’re asking is not “how does this work?” but rather “did this guy really not understand pointers at all or is there a sublime genius at work?” all the time, that question comes back. because so many idioms aren’t taught or learned but rather invented in response to some absurd compiler diagnostic message with so many pages of template instantiation context that you don’t even read it before you’re like “what if i add &, *, const, new, (), or public:, then does the problem go away?”

people dereference pointers to out-of-scope variables because fundamentally no one knew they were making the decision about whether the container stores objects or pointers, and yet here we are, with the decision made. instead of the C++ abstraction letting us forget about lifetime questions (like java does), we’re left with needing to be even more acutely aware of hidden or implied memory management than when we’re programming C. and yet nobody is!!

To me, C++ was always a rushed and “just good enough” solution. It’s clunky all over, from the way it does vtables, spaghetti includes and the ugliest operator overloading. The steam printing is outright criminal, more of demo showcase for operator overloading, that just lingered and made it into the text books, yuck. Namespaces seemed an attempt to address some of the ugly, but just made it even uglier.

Worst of all it was the start of “self documenting” APIs. Before you would get MSDN article and an API documentation written by a technical writer. With C++ you got the auto generated documentation based on a class structure, cheap!

OOP sucks and C++ is largely to blame for OOP’s market acceptance and growth so I blame it for that too.

Cue the OOP sycophants wailing and gnashing of teeth about why I’m wrong.

oop is fine, so long as it doesn’t push out other structuring styles

I like C++ I found it for the first time alongside Arduino Uno. It does the job tho. And it invites me to think in a clear manner, I hate Python but I use it to code trading bots, so it is fine, I hate android and all the apk stuff… but I’m not an expert so i can’t tell which language is good or not.

voodoo! voodoo i say!

continues using c++ as the ancients intended

Semicolon bother!

Semicolon!

Can I get a semicolon from the congregation?

I’ve been using c++ for much of that 45 years, and still like it. I have recently done some server stuff in rust – it has it’s good points and bad point (as any language). The two biggest bad points are –

– anything connected to hardware has to be ‘unsafe’ fairly quickly, thus removing some of the rust benefit.

– it isn’t OOP. I’ve noticed younger programmers who have been using it all their life don’t find that a problem – however the whole trait system, which works well if done properly (like writing c++ properly) rapidly turns un maintainable mess if done badly (like C++). And the bigger it gets, the harder to do it right (even more so than c++).

I, who have been programming daily for many decades, find rust to be great and horrible at the same time. It is extremely frustrating to get things structured right, and compiled, but then they tend to work…

The missed opportunity is a shame, if they had made rust OO, and left much of the rest of it, it may have finally been a replacement for C++…

If you’re writing unsafe code in an unsafe block then you’re doing it wrong. It’s there for the tiny blocks of code that can’t be proved safe by the compiler, and instead require you to ensure the safety. If the code in the unsafe block is safe, then the compiler can ensure the safety of everything else above it.

Compare that to C/C++/whatever, where it’s all unsafe.

Ada is also 45 years old this month!

Yet somehow 45 years ahead of C++!

Forget c++. Just use python

I use both C/C++ and python. Both have different applications. While micropython exists it is not the best for MCUs. I use python for scripting, scraping, testing algorithms, data processing, etc. I use C/C++ to write time critical applications on MCUs.

As an embedded software engineer I use both C and C++.

It wasn’t until C++14 and C++17 came out that I started to see the usefulness of modern C++ for embedded. Before that I only used C for embedded.

When I learned C++ the first time (pre C++11) I learned to try to fit everything in classes. This was a mistake. Classes are only useful when you want objects with an interface and don’t want to work with structs with function pointers, but many projects I made have only one instance of many things and you want to avoid singletons. Most projects I work with are functional, not object oriented. Basically only GUI objects (widgets) I use are objects.

What do I use C++ for?

-static assertions

-constexpr functions and templates to do calculations and initialization at compile time, avoiding code generation and macros (e.g. generate lookup tables, convert base64 strings to byte arrays).

-smart data structures, structs with useful (default) constructors and conversion methods

-RAII for things like critical sections and slave selection for SPI.

-I generally avoid dynamic allocation, but when I do use it I use smart pointers.

-std::min, std::max, std::clamp

-namespaces

-enum class

I disable RTTI and exceptions and avoid using certain stack heavy standard libraries such as regex.

I have never applied modules to an embedded project, but the ability to avoid the preprocessor seems attractive. I also want to use Coroutines in the future.

And c++ still sucks .. it should be C or even better Pascal

Instead of just Pascal … think Object Pascal Borland style … Like Delphi. That was truly RAD. Those were heady days. Of course you can use straight Free Pascal and even Lazarus for similar experience today.

C++ doesn’t suck, it just needs to be used properly. Ie. KISS. Stay way from the obtuse, edge features they keep coming up with. That goes for any language, even Python… Don’t try to be ‘clever’. Write the code with the next maintainer in mind. Don’t overdo OOP. That said, now your off to a much better C++ experience :D .

“Write the code with the next maintainer in mind.” Because the next maintainer is probably YOU.

Wow. Who has time to debate this? Obviously more than I thought. I’m trying to keep up with user stories and open looped work assignments that ignore the details of getting it out the door on time. That leaves me with long work days to try and please the mgmt.

I think I hate computers.