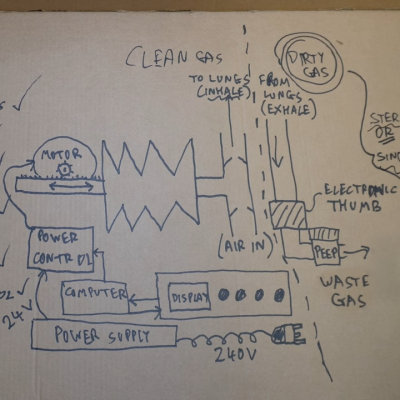

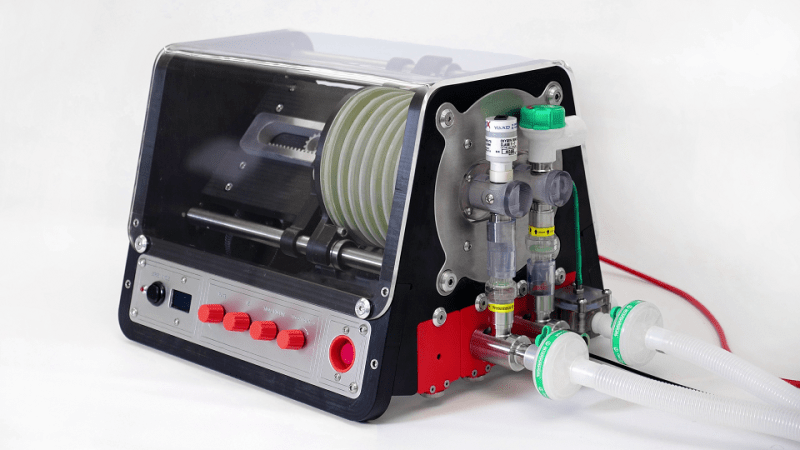

What would it be like to have to design and build a ventilator, suitable for clinical use, in ten days? One that could be built entirely from locally-sourced parts, and kept oxygen waste to a minimum? This is the challenge [John Dingley] and many others faced at the start of COVID-19 pandemic when very little was known for certain.

Back then it was not even known if a vaccine was possible, or how bad it would ultimately get. But it was known that hospitalized patients could not breathe without a ventilator, and based on projections it was possible that the UK as a whole could need as many as 30,000 ventilators within eight weeks. In this worst-case scenario the only option would be to build them locally, and towards that end groups were approached to design and build a ventilator, suitable for clinical use, in just ten days.

[John] decided to create a documentary called Breathe For Me: Building Ventilators for a COVID Apocalypse, not just to tell the stories of his group and others, but also as a snapshot of what things were like at that time. In short it was challenging, exhausting, occasionally frustrating, but also rewarding to be able to actually deliver a workable solution.

In the end, building tens of thousands of ventilators locally wasn’t required. But [John] felt that the whole experience was a pretty unique situation and a remarkable engineering challenge for him, his team, and many others. He decided to do what he could to document it, a task he approached with a typical hacker spirit: by watching and reading tutorials on everything from conducting and filming interviews to how to use editing software before deciding to just roll up his sleeves and go for it.

We’re very glad he did, and the effort reminds us somewhat of the book IGNITION! which aimed to record a history of technical development that would otherwise have simply disappeared from living memory.

You can watch Breathe for Me just below the page break, and there’s additional information about the film if you’d like to know a bit more. And if you are thinking the name [John Dingley] sounds familiar, that’s probably because we have featured his work — mainly on self-balancing personal electric vehicles — quite a few times in the past.

Thank you for taking the time to write this. “Ignition!” is a seminal tome, and any work that can be compared to it is worthy of note. I read with interest that the author notes “based on projections it was possible that the UK as a whole could need as many as 30,000 ventilators within eight weeks”.

There’s a lot to unpack here, but I would gently observe that 1. the UK imports a vast amount of talent to be able to achieve adequate care for it’s ventilated patients in non-crisis times, and 2. the UK tends to have two anaesthetic machines per operating theatre (each of which is capable of ventilation, and in time of crisis most elective operating is/was cancelled).

I propose that history is littered with examples of scientists or engineers or specialists rushing to deliver what they see as the solution. I do not deny their kind intent. I observe only that as a specialist we cannot sometimes see our own blind-spots. If I might give a grossly over-simplified example: If a patient is allowed to self-refer to a consultant bone surgeon (as is the case in some countries), that specialist might reasonably assume the causative pathology is wear and tear, and miss the underlying hormonal or cancerous cause that would have been considered by a general practitioner, if the patient were required to take the problem first to a generalist before it could be referred to a specialist.

Out of respect for those specialists who laboured on this project, I leave the conclusion as an exercise to the reader.

There are about 6,000 operating theaters in the UK. I didn’t find numbers for how many perform only elective surgeries and so could be diverted to patient support, but it still seems like a substantial shortfall compared to 30,000.

At the time it seemed weird to me that we didn’t just build more of the ventilators that were already designed and validated and which also had all of their manufacturing tooling designed.

At some point when the UK’s prime-minister was in hospital with Covid I saw a couple of doctors presenting a youTube video on what support was needed for patients on ventilators and it was immediately obvious that running off and designing more ventilators, although good natured, was as misguided as Elon Musk’s attempts to devise methods of extraction for those children stuck in the flooded Thai cave system.

The ventilator factory isn’t next to the hospital. Disrupted global supply chains turned an already long lead time to spin up production into a complete unknown. It was worth considering other options even if they ended up not being used.

The difference with Musk was that he insisted his improvised solution was obviously better than the suggestions of experts close to the situation. It’s one thing to make a suggestion. It’s another to insult anyone who doesn’t like your idea.

I came to say essentially the same thing. To produce tens of thousands of ventilators with no plan to train up thousands of vent techs put the lie to the whole situation. It’s like pledging to build thousands of bombers for a war, with no plan to train any pilots.

Great engineering work in this project, shows what people can achieve when they really strive, but ofcourse the reality was that ventilators were never needed in great numbers, and infact may have played a role in worsening the condition of some of the people put on them. The reality was that Sweden, and later Florida too, showed the best way to respond to the 2020/21 crisis, neither found itself needing great numbers of ventilators, nor even needing particularly out-of-the-ordinary numbers of hospital beds.

Because everyone died, right?

This comment would have been deleted prior to 2024. Hopefully they stop acting like fools and start recording COVID vaccine status in studies soon.

Not wanting to take away from this at all, but I’m very interested in learning more about Mercedes-AMG Petronas F1 team’s involvement in this. I remember reading an article on how they developed a new CPAP in under 100 hours and had the capacity to produce 1000 a day. It’s amazing what a company with all those resources and engineers can do in other industries. Makes you wonder why the companies that make these devices in the first place can’t do as good of a job.

I’m going to have to disagree with “Back then it was not even known if a vaccine was possible”. The gene sequence for COVID was available for researchers by January 10, 2020. Moderna was able to develop an mRNA vaccine from that information by late February, and started clinical trials in Seattle on March 16. The earliest news story I could find mentioning the idea of creating 3rd-party ventilators was March 2.

Comment removedI purchased an oxygen concentrator. Actually I ordered two, but one didn’t turn up due to price gouging (the supplier suddenly realised the prices were going up wildly!)

Luckily, I didn’t need it for covid (yet). But a friend had bad pneumonia a few months ago, so I lent it to him, with a blood O2 sensor, and it saved the NHS a hospital bed.

There were a lot of alternatives to ventilators (like Albuterol inhalers) that were readily available and far, far, safer than the vents where the primary danger is the necessary medically induced coma, and followed close behind by physical injury to the lungs by the vent pressure itself.

My father had COPD before and after he got COVID, and the treatments he was already getting for the emphysema effectively treated his COVID symptoms. The emphysema killed him a month after he beat COVID.

One of the major mistakes was to ventilate severe cases catching COVID-19 by tracheal intubation. This measure didn’t help and is even suspect to be possibly harmful. What actually helped was treatment of pneumonia with antibiotics to fight secondary infections, which are common in pneumonia cases. It is important to learn from this experience.

Um. Wow. I will throw in that unless you are or were a critical care physician during the pandemic and have some solid evidence to back up your statements, Monday morning quarterbacking is a real bad look.

May 4, 2023

What really killed COVID-19 patients: It wasn’t a cytokine storm, suggests study

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2023-05-covid-patients-wasnt-cytokine-storm.html

Secondary bacterial infection of the lung (pneumonia) was extremely common in patients with COVID-19, affecting almost half the patients who required support from mechanical ventilation. By applying machine learning to medical record data, scientists at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine found that secondary bacterial pneumonia that does not resolve was a key driver of death in patients with COVID-19. It may even exceed death rates from the viral infection itself.

The scientists also found evidence that COVID-19 does not cause a “cytokine storm,” so often believed to cause death.

The study was recently published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

“Our study highlights the importance of preventing, looking for and aggressively treating secondary bacterial pneumonia in critically ill patients with severe pneumonia, including those with COVID-19,” said senior author Dr. Benjamin Singer, an associate professor of medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and a Northwestern Medicine pulmonary and critical care physician.

The investigators found nearly half of patients with COVID-19 develop a secondary ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia.

Ok.

First off if you have respiratory failure from COVID itself so bad you need a ventilator, your mortality without said ventilator would approach 1.0.

Second, “secondary pneumonia that does not resolve” causing death is pretty similar to saying “blood loss after getting shot that doesn’t resolve” had a high mortality.

VAP (ventilator associated pneumonia) is a really real thing with a really real mortality. But if you have septic pneumonia from a virus your mortality is high- normal healthy patients on a ventilator for, say, surgery, have profoundly low VAP rates. Your analysis of the linked study seems to ignore the otherwise fatal disease being treated with a vent.

Ultimately short of decapitation the cause of death for everyone s cardiac and/or pulmonary failure. But to say that’s THE cause of death ignores the bullet in the aorta or massive overwhelming primary infection that contributes directly to bacterial superpneumonia

At the time it all sounded very “superhero” but the fact is no-one actually designed and built a ventilator in large quantities that was used for the pandemic. a bit of “apollo 13 movie syndrome” going on i suspect. even if they had of designed, built , validated and mass produced a ventilator. not enough people knew how to use them! many patients died from misuse of ventilators. hell they could make a simple mask and today i know of a PPE manufacturer being ignored by local govt. and hospitals. Its sad because a lot of intelligent well meaning people tried to mitigate the effects of the virus but govts /big business/ and middle managements everywhere got in the way.

Please research the fact that germ theory is a lie Terrain is everything as Pasteur himself said on his deathbed They control you with your fear Of assassins on the air Because nature wants to kill its greatest creation so logical

I’m glad I didn’t jump on that bandwagon, given the information that has come to light about how fatal the tech is if used inappropriately.