Long before the first airplanes took to the skies, humans had already overcome gravity with the help of airships. Starting with crude hot air balloons, the 18th century saw the development of more practical dirigible airships, including hydrogen gas balloons. On 7 January 1785, French inventor, and pioneer of gas balloon flight Jean-Pierre Blanchard would cross the English Channel in such a hydrogen gas balloon, which took a mere 2.5 hours. Despite the primitive propulsion and steering options available at the time, this provided continued inspiration for new inventors.

With steam engines being too heavy and cumbersome, it wasn’t until the era of internal combustion engines a century later that airships began to develop into practical designs. Until World War 2 it seemed that airships had a bright future ahead of them, but amidst a number of accidents and the rise of practical airplanes, airships found themselves mostly reduced to the not very flashy role of advertising blimps.

Yet despite popular media having declared rigid airships such as the German Zeppelins to be dead and a figment of a historic fevered imagination, new rigid airships are being constructed today, with improvements that would set the hearts of 1930s German and American airship builders aflutter. So what is going on here? Are we about to see these floating giants darken the skies once more?

A Simple Concept

Both balloons and airships are a type of aerostat, meaning an aircraft that is lighter than air and thus capable of sustained buoyancy. Much like a ship or a submarine, it uses this buoyancy to establish equilibrium with the surrounding air and thus maintain its position. In order to change their buoyancy, ships and submarines have ballast tanks, while airships can use mechanisms such as a ballonet. These are air-filled balloons inside the outer balloon which is filled with a lifting gas. Inflating the ballonet with more air or vice versa thus changes the buoyancy of the airship.

In the case of rigid airships like Zeppelins the concept of ballonet is somewhat reversed, in that the outer envelope contains air, while the lifting gas is inside gas bags attached to the upper part. If the rigid airship changes altitude using dynamic lift (i.e. using its propulsion and control surfaces), or by dropping ballast, the air pressure inside this outer envelope drops and the gas bags expand, which reduces the volume of air inside the outer envelope and thus adjusts the buoyancy.

This property makes both non-rigid (i.e. blimps, with ballonets) and rigid airships very stable platforms in most conditions with no real range limit beyond the fuel and food capacity for respectively the engines and onboard crew & passengers.

Why Airships Failed

The main issue with airships is that they are relatively large, and as a result cumbersome to handle, slow when moving, and susceptible to adverse weather conditions. In the list of airship accidents on Wikipedia one can get somewhat of an impression of the issues that airship crews had to deal with. Although there is some overlap with aircraft accidents, unique to airships is their large size which make them susceptible to strong winds and gusts, which can overpower the airship’s controls and cause it to crash.

Other accidents involved the loss of lifting gas or a conflagration involving hydrogen lifting gas. The fatal accident involving the LZ 129 Hindenburg is probably the event which is most strongly etched onto people’s minds here, although ultimately the cause of what came to be called the Hindenburg disaster was never uncovered. This accident is often marked as ‘the end of the airship era’, although that seems to be rather exaggerated in the light of continued use of airships throughout World War 2 and beyond.

What is undeniably true, however, is that the rise of airplanes during the first half of the 20th century provided strong competition for airships when it came to passenger and cargo transport. Workhorses like the Douglas DC-3 airplane came to define travel by air, while airships saw themselves reduced to mostly military, observational and commercial use where aspects like speed were less important than endurance.

Meanwhile the much smaller and simpler non-rigid blimps were a popular choice for especially stationary applications, ranging from advertising and military monitoring and reconnaissance, to recording platforms for televised sport matches. Effectively airships didn’t go away, they just stopped being Hindenburg-class sized giants.

A Fresh Try

Despite this reduced image of airships in people’s minds, the allure of these gentle giants quietly moving through the skies never went away. Beyond flashes of nostalgia and simple tourism, multiple start-ups have or are currently trying to come up with new business models that would reinvigorate the airship industry.

Notable mentions here include the semi-rigid Zeppelin NT, the hybrid Airlander 10, and more recently LTA’s rigid Pathfinder 1, which as the name suggests is a pathfinder airship. Of these the Zeppelin NT is the only one which is currently actively in production and flying. As a semi-rigid airship it doesn’t have the full supportive skeleton as a rigid airship, but instead only has a singular keel. Ballonets are further used as typical with a non-rigid design. So far seven of these have been built, for purposes ranging from tourism, aerial photography, and scientific studies.

The obvious advantage of a semi-rigid design is that it makes disassembling them for transport a lot easier. In comparison a hybrid airship like the Airlander 10 blends the airship design with that of an airplane by adding wings and other design elements which make it in many ways closer to a blended wing design, just with the ability to also float.

Unfortunately for the Airlander 10, it seems to be struggling to enter production since we last looked at it in 2021, with a tentative year of 2028 currently penciled in.

So in this landscape, what is the business model of LTA (Lighter Than Air), a company started and funded by Google co-founder Sergey Brin? As reported most recently by LTA, in October of 2024 they achieved the first untether flight of Pathfinder 1. Construction of Pathfinder 1 incidentally took place at Hangar Two at Moffett airfield, which some people may recognize as one of the filming locations for Mythbuster episodes, and which is a a WW2-era airship hangar.

The rigid Pathfinder 1 uses many new technologies and materials, including titanium hubs and carbon fiber reinforced polymer tubes for the internal frame, LIDAR sensors and an outer skin made of laminated polyvinyl fluoride (PVF, trade name Tedlar). It also uses a landing gear adapted from the Zeppelin NT, with LTA having a working relationship with the company behind that airship.

Finally, it uses 13 helium bags made of ripstop nylon fabric with urethane coating, which should mean that leakage of the lifting gas is significantly less than with Hindenburg-era airships, which were originally designed to use helium as well. The use of titanium and carbon fiber also offer obvious advantages over the duralumin aluminium-copper alloy that was the peak of materials research in the 1930s.

From reading the press releases and the industry commentary to LTA’s efforts it is clear that there’s no clear-cut business model yet, and that Pathfinder 1 along with the upcoming Pathfinder 3 – which will be one-third larger – are pretty much what the name says. As a start-up bankrolled by someone with very deep pockets, the immediate need to attract funding is less severe, which should allow LTA to trial multiple of these prototype airships as they figure out what does and what does not work, also in terms of constructing these massive airships.

Perhaps much like the humble hovercraft which saw itself overhyped last century before seemingly vanishing by the late 90s from public view, there is a niche for even these large rigid airships. Whether this will be in the form of mostly tourist flights, perhaps something akin to cruise ships but in the sky, or something more serious is hard to say.

Who knows, maybe the idea of a flying aircraft carrier like the 1930s-era USS Macon (ZRS-5) will be revived once more, after that humble airship’s impressive list of successes.

I’d like to see more about economically viable applications.

There’s advertising, and logging, and I don’t know what else. Maybe sightseeing.

+1. Its what I’m slightly skeptical about

Airships might be inexpensive to operate, but slow, and the space will be at a premium. Sightseeing is the only possible application that I can think of but even then, how long can you sightsee for? A few hours at most? You will eventually get bored.

Cruise ship comparison is kinda silly. Yes both are relatively inexpensive to operate, slow vehicles but cruise ships have no space or weight constraints. There are literal film theaters and shopping malls inside them. If you’ve ever been on a cruise, you will realise people often spend more time inside the ship than on the deck, just because you can only watch water for so long. Airships will have no such luxury entertainment options at hand, and unlike the ocean, no occasional sea-life to watch.

Everything said, I still want them to become more common! And ride one!

Airships do have LOTS of volume going for them, and fewer weight constraints than aircraft. Some airships of the 1920’s had sleeper cabins and a lounge with a piano, so the comparison with a cruise ship isn’t bad. Of course, you could also put this in an aircraft, so most of the arguments I’d make come down to how the designers want to make money. But having enough internal room for people to go jogging on a track is definitely an airship thing that airplanes can’t match.

The area that airships seem to do pretty well in commercially is extremely heavy lift into places with little or no infrastructure, similar to helicopters. If you needed to transport a nuclear containment vessel into Siberia, for instance, where everything is permafrost and there aren’t any decent roads ever, you could (maybe) gently lower it into location this way. The Hindenberg had a lift capacity of nearly 250 tons, and it wasn’t even made for lifting. Still, this would be like the Antonov 225: you only need a couple of them to serve the world’s needs.

Ahh that makes sense! I didn’t even think of that. Also 250 tons!? I think its time to admit, I must be mentally severely underestimating the scale of these aircrafts

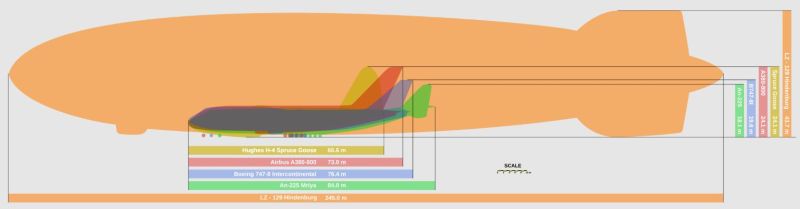

The Hindenburg was 245 meters long with a diameter of 41.2 meters

1 m3 of hydrogen can lift 1.202 kg

A cylinder that size would have a volume of 327000 m3 and be capable of lifting 432.5 tons

Hindenburg had a gross weight of approximately 107.5 tons

So the taper of its shape stole ~17.4% of its imaginary cylindrical volume

Filling it with helium would have reduced its lift by ~16.8% resulting in a still respectable cargo capacity of ~190 tons.

I think an pretty good, if niche application is remote resupply.

There are a lot of villages and small towns in the north where for at least half the year supplies are flown in. Things like $25 jugs of milk are common. A few airships on a route supplying remote and low accessible places could be really beneficial.

I would also like to see them as peaceful exploration ships.

The lack of emissions and noise would make them useful for exploring “pure” places such as the rainforest, polar regions, environmentally protected islands, etc.

Because they float, they can come to a stop at any time.

However, they may need the equivalent of airports or docks to do this safely.

Atmospheric research might be another field.

But maybe not as a storm chaser. ;)

Instead of the occasional sea life, you can watch the earth beneath you, during the day you can see cities, mountains, rivers, etc, and during the night you can see the lights in the cities and highways etc. I’d say there is way more to see from an airship than from a cruise ship.

The obvious application is air travel, albeit slower than fixed wing aircraft, without needing an airport. An airship can come down and take off in any patch of cleared ground a bit larger than the vehicle itself so long as there’s a slightly wider surrounding area without any buildings or tall trees that it could hit if caught by sudden wind gusts. So long as it is cheap to operate, and given it needs a lot less fuel than a fixed wing plane one expects it ought to be, this should be economically very feasible. Also useful in disaster zones where earthquakes, floods… have knocked out whatever runways were there beforehand.

I could see it as kind of an overland freighter. Probably more economical than sending the same amount of stuff on a train coast to coast, but would likely need train/semi to final destination.

The problem with the Airlander 10 isn’t the design, it’s the fact that they need a facility large enough to mass produce honking great airships, which they are contracted to deliver in 2026.

They’re now developing the Airlander 50 (50 tonne payload) which puts it in the league of the A380 but with considerably more leg room.

Old airships failed largely because metal fatigue was not fully understood at the time. This coupled with the primitive meteorology of the age meant they frequently encountered adverse weather and thus high stress.

If we’re serious about having low emission mass air travel airships are the way to go. We can’t manufacture low carbon jet fuel in the quantities required, and due to the low thrust and energy requirements airships can do it – even able to use electric propulsion.

Fancy steak dinners and ballroom dancing and steampunk conventions

I’d love to see some made for fighting wild fires. Have options for a tank and for pumping from a remote water source. Some remotely controlled high pressure nozzles and I could see it potentially saving many homes and lives when fires are getting out of hand here in the crispy American West. The fact that it can float for long periods without burning massive amounts of fuel and has massive lift capacity seems to be an excellent use case for them.

Unfortunately, the high winds and convection currents around wildfires make them the next to last place you’d want to operate one. Last place still belongs to thunderstorms.

I’m suprised no one said it yet but they’d probably work well as drone delivery hubs (motherships).

CargoLifter AG had a pretty good concept. (I’m actually a little disappointed that this article doesn’t mention them.) The goal was to build a freighter airship capable of lifting a 160T standard shipping container. Preliminary market studies showed that this would drastically reduce the costs for special and oversize load transports. No more need to close roads, prepare special ships, shut down overhead power lines etc. Just pick up the giant turbine, and drop it off directly at the power plant somewhere in Venezuela.

They got pretty far with their project. They’d built a giant hangar, developed all the necessary techniques and materials. But when it came to building the actual prototype, they ran out of money and had to shut down. The legal fallout was pretty hefty, but in the end, external analysts agreed that the concept would have worked and be economically viable, if someone had just stepped up and paid the unexpected additional development costs.

The german Wikipedia page about them is a bottomless rabbit hole. Proceed with caution.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cargolifter

A lot of people have already made postings about freight possibilities. But most of them have favored long distance and remote supply chain logistics.

I see a greater potential in short distance freight and Urban supply chain logistics. Imagine the potential of an Amazon Airships flying across suburban and urban centers with fleets of drones managing deliveries along the way.

N807XR, Lockheed Martin Tethered Aerostat Radar System for Customs and Border Protection at the Cudjoe Key Air Force Site.[1] Track it:

https://globe.adsbexchange.com/?icao=aafdfb

[1] Tethered Aerostat Radar System

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tethered_Aerostat_Radar_System

So it’s a really expensive hobby project? I think most of us here can identify with that, in premise if not in scale…

I’ve been thinking of using a fleet of autonomous airships to haul cargo around the globe. Loading/unloading cargo is done by robots far away from humans in case of fire. The balloons could then be filled with cheap hydrogen, and then electric motors and fuel cells could be used for landing/coarse corrections. Then let them float into the jet streams circling the globe. When they get close to their destination the hydrogen is used to run the motors for descent/landing. Consuming the hydrogen reduces buoyancy which is a desirable side effect during landing.

I wonder if this could work? I want this to work.

every time i think of wasting such an enormous quantity of helium, i get sad

Only about 8% more lifting power

Citation? Or is it just the voices again?

It’s astounding how much people’s sense of humor has degraded into literalism

Humor is a serious matter, I think. Like waterstuff.

The first manned hydrogen balloon flight was December 1, 1783. First death (2 deaths actually) June 15th 1785 in a Roziere Balloon, a hot air/hydrogen dual envelope hybrid….it crashed but didnt explode. The Hindenberg (1937) killed 26 immediately with 10 more succubing to their injuries in the days and weeks that followed. 62 passengers/crewmembers survived 37% fatality.

The worst dirigible explosion of record happened 4 years earlier when 73 of 76 members of the USS Akron perished. 73 the worst death toll despite military use of manned hydrogen balloons from Napoleon to World War I. But the hindenberg pretty much ended 154 years of hydrogen balloon advancement.

The first powered heavier than air flight happened dec 17 1903. The first death September 17, 1908. Japan Airlines Flight 123, the most deadly single plane crash killed 520 with only 4 survivors in 1985.JA Flight 123 is only one of 30 fatal crashes involving 747s. As of February 2025, there were 426 Boeing 747s in active airline service.

Consider http://www.planecrashinfo.com/worst100.htm

The 99 worst aviation disasters (excluding the Towers) claimed 19573 lives….and thats just the worst of the worst, with the oldest of those being 1962. Yet we still fly planes.

Im with Walternate, Nothing wrong with a lil H₂

Rip cargolifter

Maybe I’m crazy, but don’t flying yachts seem to be a decent application for airships, at least starting out?

Sure, their size isn’t comparable with a modern cruiseship… but it can be compared to modern yachts. If the cost wouldn’t be significantly higher than a boat, it’s an option. Surely, the flight cabin can be enlarged, since it’s supposed to carry loads?

If I had the money, I’d certainly prefer an airship over a boat. They can cross the ocean, but can also cross land. More to see, more flexibility. Better views, certainly. There’s many benefits.

Hi,

with asymmetric warfare ans piracy being a thing again, i’d rather not be visible from the ground for large periods of time.

So, speed zepps, or armored (kevlar?) ones?

Make a fleet or a “constellation,” and slap some WiFi modules on them and provide internet to the ground. Call it….Skylink.

The recently found 8mm home movie full side view is overwhelmingly convincing for what happens when a floating Leyden Jar in charged sky is suddenly grounded. Capt didn’t want to land need to wait 1 hour, no we have press and such for the new season’s voyages must be on time! He flew the Graf around the world in ’29, which had a female reporter for Hearst papers start the mile high club. US Navy has the most loss to it’s credit.

We know a lot more about weather now. I wouldn’t mind a passing zeppelin, it’s skyslugs and their persistent trails all over the sky on what would be a blue sky day I dislike. 911 proved things here.

A paper from way back

https://id.iit.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Aerotecture.pdf

Airships in space

http://www.jpaerospace.com/ATO/ATO.html

Venus airships

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/High_Altitude_Venus_Operational_Concept

I don’t think Powell’s airship-to-orbit is doable—but an airship FROM orbit is.

At Venus, the envelope of the airship itself only needs inflating to Earth sea-level gas—thus the whole structure is the gondola.

I would launch big rockets, and inflate them in space—with materials like what is seen here:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Low-Earth_Orbit_Flight_Test_of_an_Inflatable_Decelerator

Voyager—the Star Trek ship—is the one design that lends itself into being an airship.