At 5:20 PM on November 9, 1965, the Tuesday rush hour was in full bloom outside the studios of WABC in Manhattan’s Upper West Side. The drive-time DJ was Big Dan Ingram, who had just dropped the needle on Jonathan King’s “Everyone’s Gone to the Moon.” To Dan’s trained ear, something was off about the sound, like the turntable speed was off — sometimes running at the usual speed, sometimes running slow. But being a pro, he carried on with his show, injecting practiced patter between ad reads and Top 40 songs, cracking a few jokes about the sound quality along the way.

Within a few minutes, with the studio cart machines now suffering a similar fate and the lights in the studio flickering, it became obvious that something was wrong. Big Dan and the rest of New York City were about to learn that they were on the tail end of a cascading wave of power outages that started minutes before at Niagara Falls before sweeping south and east. The warbling turntable and cartridge machines were just a leading indicator of what was to come, their synchronous motors keeping time with the ever-widening gyrations in power line frequency as grid operators scattered across six states and one Canadian province fought to keep the lights on.

They would fail, of course, with the result being 30 million people over 80,000 square miles (207,000 km2) plunged into darkness. The Great Northeast Blackout of 1965 was underway, and when it wrapped up a mere thirteen hours later, it left plenty of lessons about how to engineer a safe and reliable grid, lessons that still echo through the power engineering community 60 years later.

Silent Sentinels

Although it wouldn’t be known until later, the root cause of what was then the largest power outage in world history began with equipment that was designed to protect the grid. Despite its continent-spanning scale and the gargantuan size of the generators, transformers, and switchgear that make it up, the grid is actually quite fragile, in part due to its wide geographic distribution, which exposes most of its components to the ravages of the elements. Without protection, a single lightning strike or windstorm could destroy vital pieces of infrastructure, some of it nearly irreplaceable in practical terms.

Tasked with this critical protective job are a series of relays. The term “relay” has a certain connotation among electronics hobbyists, one that can be misleading in discussions of power engineering. While we tend to think of relays as electromechanical devices that use electromagnets to make and break contacts to switch heavy loads, in the context of grid protection, relays are instead the instruments that detect a fault and send a control signal to switchgear, such as a circuit breaker.

Relays generally sense faults through a series of instrumentation transformers located at critical points in the system, usually directly within the substation or switchyard. These can either be current transformers, which measure the current in a toroidal coil wrapped around a conductor, much like a clamp meter, or voltage transformers, which use a high-voltage capacitor network as a divider to measure the voltage at the monitored point.

Relays can be configured to use the data from these sensors to detect an overcurrent fault on a transmission line; contacts within the relay would then send 125 VDC from the station’s battery bank to trip the massive circuit breakers out in the yard, opening the circuit. Other relays, such as induction disc relays, sense problems via the torque created on an aluminum disk by opposing sensing coils. They operate on the same principle as the old mechanical electrical meters did, except that under normal conditions, the force exerted by the coils is in balance, keeping the disk from rotating. When an overcurrent fault or a phase shift between the coils occurs, the disc rotates enough to close contacts, which sends the signal to trip the breakers.

The circuit breakers themselves are interesting, too. Turning off a circuit with perhaps 345,000 volts on it is no mean feat, and the circuit breakers that do the job must be engineered to safely handle the inevitable arc that occurs when the circuit is broken. They do this by isolating the contacts from the atmosphere, either by removing the air completely or by replacing the air with pressurized sulfur hexafluoride, a dense, inert gas that quenches arcs quickly. The breaker also has to draw the contacts apart as quickly as possible, to reduce the time during which they’re within breakdown distance. To do this, most transmission line breakers are pneumatically triggered, with the 125 VDC signal from the protective relays triggering a large-diameter dump valve to release pressurized air from a reservoir into a pneumatic cylinder, which operates the contacts via linkages.

The Cascade Begins

At the time of the incident, each of the five 230 kV lines heading north into Ontario from the Sir Adam Beck Hydroelectric Generating Station, located on the west bank on the Niagara River, was protected by two relays: a primary relay set to open the breakers in the event of a short circuit, and a backup relay to make sure the line would open if the primary relays failed to trip the breaker for some reason. These relays were installed in 1951, but after a near-catastrophe in 1956, where a transmission line fault wasn’t detected and the breaker failed to open, the protective relays were reconfigured to operate at approximately 375 megawatts. When this change was made in 1963, the setting was well above the expected load on the Beck lines. But thanks to the growth of the Toronto-Hamilton area, especially all the newly constructed subdivisions, the margins on those lines had narrowed. Coupled with an emergency outage of a generating station further up the line in Lakeview and increased loads thanks to the deepening cold of the approaching Canadian winter, the relays were edging closer to their limit.

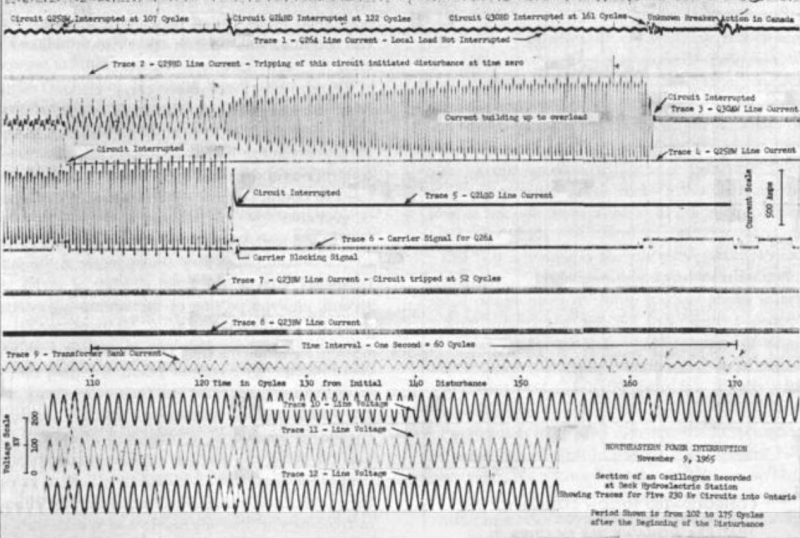

Data collected during the event indicates that one of the backup relays tripped at 5:16:11 PM on November 9; the recorded load on the line was only 356 MW, but it’s likely that a fluctuation that didn’t get recorded pushed the relay over its setpoint. That relay immediately tripped its breaker on one of the five northbound 230 kV lines, with the other four relays doing the same within the next three seconds. With all five lines open, the Beck generating plant suddenly lost 1,500 megawatts of load, and all that power had nowhere else to go but the 345 kV intertie lines heading east to the Robert Moses Generating Plant, a hydroelectric plant on the U.S. side of the Niagara River, directly across from Beck. That almost instantly overloaded the lines heading east to Rochester and Syracuse, tripping their protective relays to isolate the Moses plant and leaving another 1,346 MW of excess generation with nowhere to go. The cascade of failures marched across upstate New York, with protective relays detecting worsening line instabilities and tripping off transmission lines in rapid succession. The detailed event log, which measured events with 1/2-cycle resolution, shows 24 separate circuit trips with the first second of the outage.

While many of the trips and events were automatically triggered, snap decisions by grid operators all through the system resulted in some circuits being manually opened. For example, the Connecticut Valley Electrical Exchange, which included all of the major utilities covering the tiny state wedged between New York and Massachusetts, noticed that Consolidated Edison, which operated in and around the five boroughs of New York City, was drawing an excess amount of power from their system, in an attempt to make up for the generation capacity lost from upstate. They tried to keep New York afloat, but the CONVEX operators had to make the difficult decision to manually open their ties to the rest of New England to shed excess load about a minute after the outage started, finally completely isolating their generators and loads by 5:21.

Heroics aside, New York City was in deep trouble. The first effects were felt almost within the first second of the event, as automatic protective relays detected excessive power flow and disconnected a substation in Brooklyn from an intertie into New Jersey. Operators at Long Island Light tried to save their system by cutting ties to the Con Ed system, which reduced the generation capacity available to the city and made its problem worse. Operators tried to spin up their steam turbine plants to increase generation capacity, but it was too little, too late. Frequency fluctuations began to mount throughout New York City, resulting in Big Dan’s wobbly turntables at WABC.

As a last-ditch effort to keep the city connected, Con Ed operators started shedding load to better match the dwindling available supply. But with no major industrial users — even in 1965, New York City was almost completely deindustrialized — the only option was to start shutting down sections of the city. Despite these efforts, the frequency dropped lower and lower as the remaining generators became more heavily loaded, tripping automatic relays to disconnect them and prevent permanent damage. Even so, a steam turbine generator at the Con Ed Ravenswood generating plant was damaged when an auxiliary oil feed pump lost power during the outage, starving the bearings of lubrication while the turbine was spinning down.

By 5:28 or so, the outage reached its fullest extent. Over 30 million people began to deal with life without electricity, briefly for some, but up to thirteen hours for others, particularly those in New York City. Luckily, the weather around most of the downstate outage area was unusually clement for early November, so the risk of cold injuries was relatively low, and fires from improvised heating arrangements were minimal. Transportation systems were perhaps the hardest hit, with some 600,000 unfortunates trapped in the dark in packed subway cars. The rail system reaching out into the suburbs was completely shut down, and Kennedy and LaGuardia airports were closed after the last few inbound flights landed by the light of the full moon. Road traffic was snarled thanks to the loss of traffic signals, and the bridges and tunnels in and out of Manhattan quickly became impassable.

Mopping Up

Almost as soon as the lights went out, recovery efforts began. Aside from the damaged turbine in New York and a few transformers and motors scattered throughout the outage area, no major equipment losses were reported. Still, a massive mobilization of line workers and engineers was needed to manually verify that equipment would be safe to re-energize.

Black start power sources had to be located, too, to power fuel and lubrication pumps, reset circuit breakers, and restart conveyors at coal-fired plants. Some generators, especially the ones that spun to a stop and had been sitting idle for hours, also required external power to “jump start” their field coils. For the idled thermal plants upstate, the nearby hydroelectric plants provided excitation current in most cases, but downstate, diesel electric generators had to be brought in for black starts.

In a strange coincidence, neither of the two nuclear plants in the outage area, the Yankee Rowe plant in Massachusetts and the Indian Point station in Westchester County, New York, was online at the time, and so couldn’t participate in the recovery.

For most people, the Great Northeast Power Outage of 1965 was over fairly quickly, but its effects were lasting. Within hours of the outage, President Lyndon Johnson issued an order to the chairman of the Federal Power Commission to launch a thorough study of its cause. Once the lights were back on, the commission was assembled and started gathering data, and by December 6, they had issued their report. Along with a blow-by-blow account of the cascade of failures and a critique of the response and recovery efforts, they made tentative recommendations on what to change to prevent a recurrence and to speed the recovery process should it happen again, which included better and more frequent checks on relay settings, as well as the formation of a body to oversee electrical reliability throughout the nation.

Unfortunately, the next major outage in the region wasn’t all that far away. In July of 1977, lightning strikes damaged equipment and tripped breakers in substations around New York City, plunging the city into chaos. Luckily, the outage was contained to the city proper, and not all of it at that, but it still resulted in several deaths and widespread rioting and looting, which the outage in ’65 managed to avoid. That was followed by the more widespread 2003 Northeast Blackout, which started with an overloaded transmission line in Ohio and eventually spread into Ontario, across Pennsylvania and New York, and into Southern New England.

No, they are still literally relays: electromechanical or solid state switches. They’ve simply been set up to trigger from a fault signal from some kind of a sensor. Making the distinction like they’re something entirely different is just causing confusion.

Though when I say “still”, I mean in category.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relay

Back then they would have been actual relays in the traditional sense whereas today they are simply called relays. These days they’re called relays for the function rather than the construction.

I like that you argued with yourself until both comments became irrelevant. This is super-position annihilation.

Come on, it was very clear what he meant – these relays do not directly open or close the circuit directly, as you might expect, but trigger a separate circuit breaker.

He wasn’t saying they were of some un-relay like design.

A relay does not need to switch something directly to be a relay.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UbLfAtow51k

A relay relays the fault signal to the actuator that opens or closes the breakers. That’s why we call them relays.

There might even be multiple relays along the way to the big motor that actually moves the big switches on the power line, or there might be signal relays before the one relay that is nominated as the safety relay, because the actual sensor might be somewhere deep inside the machinery and the signal needs relaying before it reaches the control board. The term safety relay is simply given to a relay that sits in the logical section of the circuit meant for handling fault signals.

It’s like saying, your microphone’s built-in pre-amp is not an amplifier but “an instrument for detecting sound and sending out audio signals” because it does not directly drive the speakers. It’s a distinction without a true difference.

We all know the real cause of the power outage in 1965. A time traveller had his mafia buddies plug in a hair dryer outside a frat house so he could make the final leap home. It didn’t work.

James Burke had a great video about this in Connections, season 1, episode 1.

That was such a great series, and the book is also excellent, with even more detail.

I love his explanation of the rise of human technology via the connected chain of inventions each triggering the next…

James Burke, okay.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Connections_(British_TV_series)

Practical Engineering? (civil engineering channel on YT) also did a great video on this topic under the title of “Cascading Power Failures” iirc

Don’t be ridiculous. It’s industry jargon, and it related to starting equipment when all other sources of illumination are gone.

“Black Start” is an actual term and not a racially charged offense. (neither is “the Hispanic word for black” nor “a particular country in Africa”)

One should resist their knee-jerk reaction to such terms until they observe the entirety of the term’s usage to determine if it SHOULD be considered offensive or not; then once its observed to not be offensive, one would calm the fork down. :)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_start

“A black start is the process of restoring an electric power station, a part of an electric grid or an industrial plant, to operation without relying on the external electric power transmission network to recover from a total or partial shutdown.[1]”

edit: this was in response to someone saying “black start” was an offensive term. sorry and moderate my comment as necessary. :)

You means those Amurricans that were duped into voting for this guy in that said he wanted only to be dictator for one day? And then proceeded to turn that Country into an polices state?

I understand you will not be able to agree, least of all because you mark yourself an domestic terrorist…

Oh dear, maybe stop watching CNN and MSNBC for 5 mins and you might realise which side was really duped, and had been for a very long time.

And also shame on us for bringing decisive politics into a comment thread about technology.

I genuinely hope you have a good day…

This is a Hackady comment section, lets not delve into politics here

Was that “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia”?

Not unless Georgia recently moved from the northeast

Someone was playing a Hammond organ with instruments and choir and wondering why the pitch strayed off pitch. What the – oh I’m in church. A Capella now.

This was immortalised in the classic 1980 song ‘747 (Strangers in the Night)’ by Saxon – detailing the issues an aircraft trying to land at JFK had when all the runway lights and air traffic control radio went dead – and no other airport in the area to divert to, as they couldn’t be contacted either.

Love that, thank you. Saxon also made a cover of Ride with The Wind.

If you ever visit Niagra, the old power plant is well worth a visit. Incredible and beautiful engineering.

Agreed – that was the best part of our trip to Niagara falls this past summer. Went during the day and went back for their night event, thought it might be hokey, but it was quite impressive.

All about that:

James Burke in BBC Connections, Ep. 1 “The Trigger Effect”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XetplHcM7aQ

I had a small role in the recovery from the ’65 blackout. In 1968 I was a sophmore at college with a work-study appointment with Penelec (the Pennsylvania Power Company), working for Penelec six months and studying electrical engineering the other six months. At that time, Penelec was running a study on the state’s power grid to determine the over-current values on each line if one or more segments were off-line. Up to that time, over-current estimates were limited to calculations based on one adjacent line being down. The ’65 blackout proved that approach to be inadequate. Penelec had recently acquired an IBM 360 and now had the number-crunching capability to expand their calculations to consider multiple lines down simultaneously. I was given a printout from one study and a Remington-Rand mechanical calculator – the kind with the big crank arm on one side – and was told to perform a set of calculations for each line of the printout. I was calculating actual values to use to reset the small current-sensing relays in the substations across the state. The printout ran hundreds of pages with each page containing dozens of lines. Took me two weeks to get through the assignment. I’ve no idea why the 360 didn’t do those particular calculations in the first place. I suppose someone decided modifying the code and running the entire simulation again was more expensive than having the kid (me) do it by hand for some ‘work experience.’

I did get some first-hand exposure to the substation control rooms and saw the tiny jewel-like relays that monitored the current and initiated the trip sequence to take a transmission line offline. I also got to hear the OCBs (oil contained breakers) drop a main line. They’re the size of a minivan standing on end and when they trip they sound like one of the loud fireworks that always end the show. Except that you’re standing right next to it. What is still amazing to me is that the system back then was all mechanical – no electronics of any kind – yet it could still drop a line within one 60Hz cycle!

Thank you! :-)

I was too young to remember the blackout of 1965 but 1977, I was heavily into radio and shortwave.

For a brief time man made noise was gone and you could hear distant stations without a lot of RFI.

I was in my room when the power went out, and my father yelled my name thinking I did something.

We were both into electronics etc. due to his job at WNBC/NBC. First question out of his mouth was

what did you do? I said, hey Dad, listen. I was picking up an AM station down in Virginia.

1977 was the summer of hell. The oppressive heat, the Son of Sam terrorizing the city……

It was a wild ride….

The ’65 blackout was when I learned that a can of oil-packed sardines plus a wick of some sort (twisted paper will do) yields a usable oil lamp. You probably want to remove the sardines first.

After that we kept flashlights and a few candles in the house.

I wonder how much battery and flashlight sales jumped in the week after the blackout.

Baby oil burns cleaner and doesn’t smell unless it’s been perfumed with something. If you trim the wick short enough, it doesn’t give off smoke either.

Felix Immler have some ideas for improvised candles:

https://youtu.be/LOAOweqNvqs?si=WndvMu8mhvDIUtzj