When the Channel Tunnel opened in 1994, the undersea rail link saw Britain grew closer to the European mainland than ever before. However, had things gone a little differently, history might have taken a very different turn. Among the competing proposals for a fixed Channel crossing was a massive bridge. It was a scheme so audacious that fate would never allow it to come to fruition.

Forget the double handling involved in putting cars on trains and doing everything by rail. Instead, the aptly-named Euro Route proposed that motorists simply drive across the Channel, perhaps stopping for duty-free shopping in the middle of the sea along the way.

Long-Held Dreams

The concept of a permanent tunnel or transit link between Britain and France dates back a long way. The earliest recorded example is from 1802, when French engineer Albert Mathieu-Favier proposed a tunnel design for horse-drawn stagecoaches to travel between the Isles and the mainland. Ultimately, though, the feasibility of engineering such a project was beyond the limits of the time. The idea would never quite go away, though, with the British and French governments eventually coming to explore it in earnest starting in the late 1950s. The Channel Tunnel Study Group was established as an Anglo-French task force to explore the possibilities of building a crossing between the two nations. This led to an early effort to construct a cross-Channel tunnel beginning in 1973, only for the project to be scrapped two years later by British Prime Minister Harold Wilson on the basis of cost and the strains of the worldwide oil crisis.

It would be over a decade before the concept returned to the fore. The French and British governments reconvened in 1984 to establish baseline parameters for the project, before opening up the project to proposals in 1985. That process saw the Channel Tunnel Group win the day with a plan for a 51.5-kilometer dual-track rail-only tunnel, with trains carrying passengers and hauling cars between the two countries. The Treaty of Canterbury was signed in 1986, and construction began soon after, eventually leading to the infrastructure that exists today.

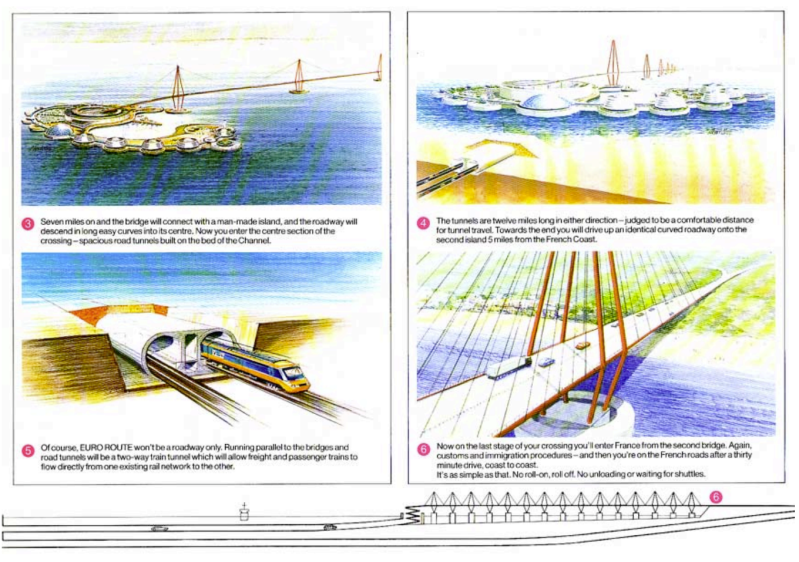

The Channel Tunnel might have been the winning project, but it wasn’t the only proposal on the table. The Euro Route project was an altogether bolder scheme. Their plan called for a three-stage crossing combining both road and rail. Cars would travel via a spectacular road link featuring bridges springing from each coast, leading into an immersed tunnel running through the deepest section of the Channel. Meanwhile, there would also be a twin-track rail tunnel not dissimilar from the Channel Tunnel itself.

The Euro Route project was marketed based on its key offering—users would be able to drive all the way with a minimum of fuss. “From your home you will drive straight to France,” read the marketing materials. There would be no fussy loading and unloading of automobiles on to train cars. Meanwhile, those that wished to travel by rail could equally do so via the separate rail tunnel, with freight trains using the passage as well.

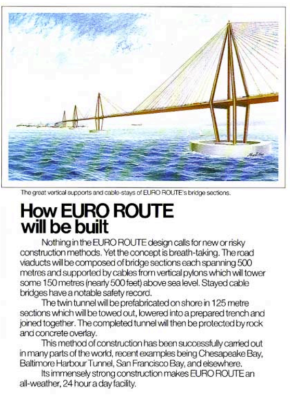

The project would not be cheap. Estimates were that it would cost some £6 billion to build (1985 prices). At the time, this figure came in at two to three times what the Channel Tunnel proposal was expected to cost—no surprise given it also involved an entire road crossing in addition to a rail tunnel. However, the project was backed by a consortium of heavyweight British institutions—including British Steel, Barclays Bank, and GEC—which had together secured over seven billion pounds in funding for the project. The intention was that it would be paid for in time by charging tolls to access the crossing.

The road crossing was designed for drama and practicality in equal measure. Motorists would leave the M20 near Dover, before passing through toll booths to pay for the journey. From there, they would make their way onto a bridge standing some fifty meters above the waves. This cable-stayed bridge would stretch for 8.5 km to an artificial island, where the motorway would spiral down beneath sea level to the undersea tunnel below. This tunnel consisted of a 21 km immersed tube tunnel carrying parallel dual carriageways safely beneath the shipping lanes, emerging at a second artificial island before another bridge carried traffic the final 7.5 km to France. A third artificial island would also sit in between the other two, serving as a ventilation shaft for the road tunnel and acting as a marker to enforce lane discipline for shipping in the Channel.

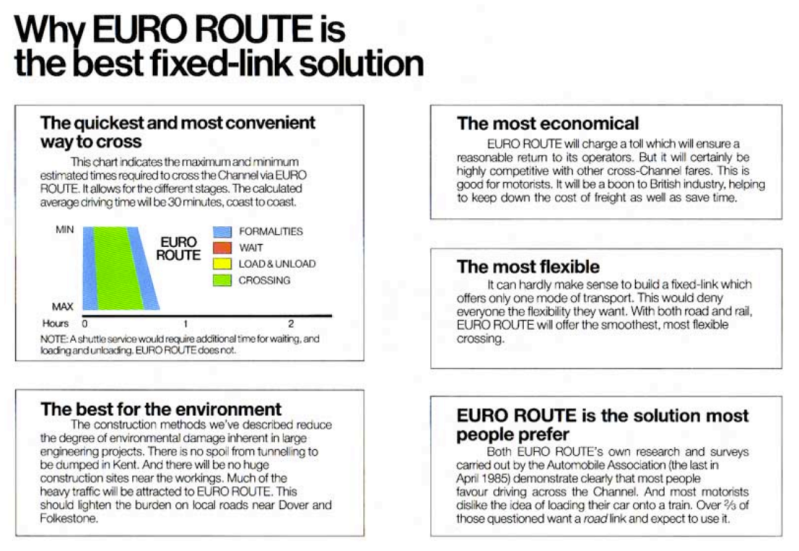

All in all, traveling the Euro Route was expected to take just 30 minutes over the road. Customs formalities were to be “speeded up by computer” to ease the journey, pushing the total time to approximately 45 minutes. This was to be a key advantage over concepts like the all-rail Channel Tunnel. “NOTE: A shuttle service would require additional time for waiting, and loading and unloading; Euro Route does not,” noted the marketing materials. . Those behind the EuroRoute believed people wanted to drive across the Channel themselves, rather than sitting in their cars on a train for a longer period of time.

The combined bridge-tunnel-bridge concept was, at first blush, more complicated than simply building a single long road tunnel from coast to coast. However, such a tunnel would have likely measured well over 30 km in length. This was considered somewhat undesirable both for the length of time spent underground and the build-up of traffic emissions. The open-air bridges were used to help break up the journey so less time would be spent in a tube beneath the waves. This design also created opportunity, for the artificial islands weren’t seen as just entry and exit points to the tunnel below. EuroRoute envisioned them as destinations in their own right, with refuelling, refreshment, and parking facilities, as well as other niceties like hotels and duty-free shopping complexes.

The rail component proposed by EuroRoute was remarkably similar to what was eventually built as part of the Channel Tunnel project. It concerned a tunnel running between Cheriton and Sangatte, though EuroRoute planned to use immersed tube construction for the majority of its length, rather than boring through the entire length as with the Channel Tunnel. Overall, though, it similarly featured two tubes for bidirectional travel, with a central shaft for maintenance access.

The Euro Route proposal noted that public sentiment was on its side. Contemporary research suggested that fifty-two percent of people preferred driving across, with many actively disliking the car shuttle concept. Yet when decision time came, the governments chose the Channel Tunnel—ultimately the simpler, cheaper rail-only proposal. The fact that the Channel Tunnel project would end up with massive budget overruns and significant delays perhaps casts that decision in a different light. At the same time, we might never know how well—or how badly—construction of the Euro Route might have gone.

EuroRoute’s bridges and islands seem destined to remain forever on the drawing board, another grand infrastructure dream that fell victim to caution and economics. But those architectural drawings still capture something important—the ambition of an era when it seemed anything could be built, even a bridge linking two former bitter enemies over the busiest shipping lanes in the world.

It reminds me of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel, which is a marvelous piece of engineering.

Of course the duty-free aspect is very important to market such a thing to the English

I had no idea about this, when I was riding my motorbike up the US east coast.

Unexpectedly emerging from a tunnel, into the middle of the sea was absolutely fantastic.

“EuroRoute envisioned them as destinations in their own right”. A truck stop? It would be much more exciting if it was placed in international water.

They were to be, I believe, so they would provide duty free shopping.

I suspect the French disliked this idea, as probably 90% of the British traffic at the time would have gone as far as the first duty free and returned home laden with cheap wine – rather than spending their money in France!

A bridge above the Channel is not an easy task to build, but even harder to keep running. Now as UK brexited, the rail tunnel traffic has plummeted both in freight and passengers, so from economic pov the revenues are low, any repairs needed are not so easely and proptly done. A bridge standing against the elements and ship traffic is a problem magnitudes bigger than the tunnel. Corrosion because of the salty water and wind, birds excrements, vehicle exhaust and bridge movement due to waves and traffic could have a speed that cannot be defeated by constant repairs.

Such a bridge will stand between two different birocraties and two different political systems. This is not terra firma but shifting sands.

And the last bit, perhaps the most important: on which side will you drive? Right like in EU or left like in UK? How many accidents will block the traffic due to confusion of what side to drive on? This (and measuring units also) difference is bigger than the width of the Channel. It’s another Beagle probe waiting to crush on another, closer, Mars.

Each will of course switch sides at their end so the drivers along the bridge can get accustomed to driving on the correct side of the road for their destination and not get confused when they finally reach there.

So when a French driver goes on the bridge they’ll change sides from right to left, and when an English driver enters the bridge they will go from left to right. This is accomplished with a special junction, like on a Scalectrix track that has to make a figure-8 on itself without a bridge piece.

As we notice, this arrangement will also save money, since two fewer lanes are required along the length of the entire bridge. Coming from the French side, the right lane is not used, and coming from the UK side the left lane is never used. With both the left and the right lane no longer in operation, we can reduce maintenance and building costs significantly.

French (europeans) drive on the right side so the left one is not”used” and british on the left so the “right” one is not used. Got myself the ideea of a bridge with “one side”, but from where will those drivers return? Perhaps a two layer bridge will cover better this. Much simpler will be to have two lanes driven european style and the switching will be done on british soil. But yet again, the practicality is voided when you think that you have to protect the vehicles from the wind and sea, thus basically you need an over the water tunnel.

Like in Hong Kong or Macau. One or both. Which has a cross over bridge.

Crossing the tunnels over would seem the most obvious!

Bridge, fake island, tunnel though.. what they did for the Öresund between Sweden and Denmark.

Sweden also had crossovers before 1967 as they drove on the left and Norway didn’t!

And on the days that hurricane remnants are driving wild winds up the channel – 150 feet above the water? You’d practically have to set a crab angle for your car!

Michigan doesn’t get hurricane but now and then the 5 miles (8km) long Mackinac Bridge has to restrict large vehicles or even completely shut down the bridge due to strong wind. At 50-65 MPH (80-105 KMH) large vehicles are stopped. Over 65, no vehicle can cross at all.

This doesn’t happen often because the climate in the area generally do not generate strong wind. English Chanel do get stronger wind due to warmer air and wider flat area which makes hurricane remains a possibility.

If a bridge was built over the Chanel, I suspect it would have had tall, angled walls on the side to protect cars, giving the bridge wing-like profile. The engineering design would have been quite challenging

Ranks right up there with a bridge across the strait of gibraltar as something that seems inevitable but impossible at the same time

The Tokyo Bay Aqua-Line is very similar to this, especially the artificial islands linking the bridge and tunnel sections that are like rest stops, and the central ventilation tunnel (which on the Aqua-Line is passively wind-powered)

In the First World War there was a scheme to close off the English Channel to U-Boats with anti submarine nets connected to concrete towers located at regular intervals across the Straits of Dover. Two towers were constructed at Southampton by the end of the war. One was demolished but the other was towed out to the Eastern End of the Solent where it was sunk in situ and used as a navigation mark. The Nab tower is still there today so it probably would have been feasible to use technology like this to create piers for a cross channel bridge.

Has there ever been a large-scale infrastructure project that hasn’t had “budget overruns”? Initial budget estimates are invariably garbage, written by people who aren’t actually the ones who do the work and therefore never learn the lessons that would enable them to improve those estimates, have massive perverse incentives to under-estimate, and do not account for the unseen problems that every long-term project is guaranteed to have a few of. And every critic and media outlet fixates on the very first number even if it’s updated over the course of the many, many years such projects take to complete.

There is not a snowball’s chance in hell that Euro Route would have been completed for the price they claimed.

The plans didn’t remain forever on the drawing board they simply were modified and used to design the Öresundsbron!

We have a similar bridge/tunnel in the US, but it’s only 28km total