We’re most familiar with sound as vibrations that travel through the atmosphere around us. However, sound can also travel through objects, too! If you want to pick it up, you’d do well to start with a contact mic. Thankfully, [The Sound of Machines] has a great primer on how to build one yourself. Check out the video below.

The key to the contact mic is the piezo disc. It’s an element that leverages the piezoelectric effect, converting physical vibration directly into an electrical signal. You can get them in various sizes; smaller ones fit into tight spaces, while larger ones perform better across a wider frequency range.

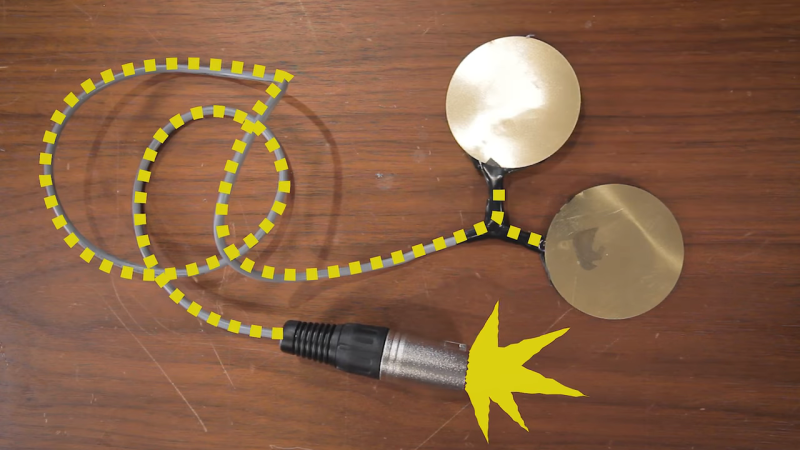

[The Sound of Machines] explains how to take these simple piezo discs and solder them up with connectors and shielded wire to make them into practical microphones you can use in the field. The video goes down to the bare basics, so even if you’re totally new to electronics, you should be able to follow along. It also covers how to switch up the design to use two piezo discs to deliver a balanced signal over an XLR connector, which can significantly reduce noise.

There’s even a quick exploration of creative techniques, such as building contact mics with things like bendable arms or suction cups to make them easier to mount wherever you need them. A follow-up explores the benefits of active amplification. The demos in the video are great, too. We hear the sound of contact mics immersed in boiling water, pressed up against cracking spaghetti, and even dunked in a pool. It’s all top stuff.

These contact mics are great for all kinds of stuff, from recording foley sounds to building reverb machines out of trash cans and lamps.

Thank you for the article. I just found a bunch of old piezos and was wondering what experiments to make with them.

So the disc on a piezo is copper ? Wow, so rigid. Thank you learn garbage a day.

Note that using more than one element will introduce directionality due to speed of sound and phase effects; this is how pickup patterns other than omnidirectional are achieved. The better solution, if that isn’t what you want, is an unbalanced to balanced conversion, either active or a transformer.

In stage terms, that’s a DI (Direct Input) box or balun.

(Part-time amateur live sound engineer, mostly folk – adjacent styles.)

Oh, I hadn’t thought of that, but of course that would be directional. That is what I want, actually what I really want is to sense xyz vibrations in a solid. Three points on a plane and some timing should do it right?

If any one is curious, or if it’s a solved problem, what I want to do is sense the direction a plucked guitar string is vibrating in.

The video is bad on many levels. For starters the metal disc isn’t copper but brass, then it skips mentioning impedance which is extremely important as those are piezoelectric transducers and most amplifiers and their inputs are designed for mic/line level signals with quite low impedance, then it uses a completely unnecessary dual mic arrangement when it could simply use one transducer wired between the two hot wires of the balanced cable, then properly connect the ground braid, that is, not connecting it at all on the transducer but leaving it connected on the plug, so it would short any noise to the amp/mixer ground. Then it fails to mention that for a contact mic to properly work, it needs a counterpoise to build some inertial mass that counters the vibrations transmitted on the other side of the piezoelectric material. Just glue a small weight on the side that isn’t in contact with the object; that would increase the output by a big margin.

Isn’t this basically a poor man’s “acoustic emission sensor” (usually paired with a DAQ for industrial sensing applications)?

Woo hoo, so Google tells me that an XYZ “acoustic emission sensor” is really a Multiaxial Force/Displacement Measurement device, and there is a whole industry making them.

Thanks, I would not have thought of that!

There’s a whole industry wrapped around mechanical analysis and failure prediction with this sort of thing. For just messing around, the VLC app has spectral analysis features to play with – it can be remarkably handy (“Is that piston slap or a stuck lifter I’m hearing?).