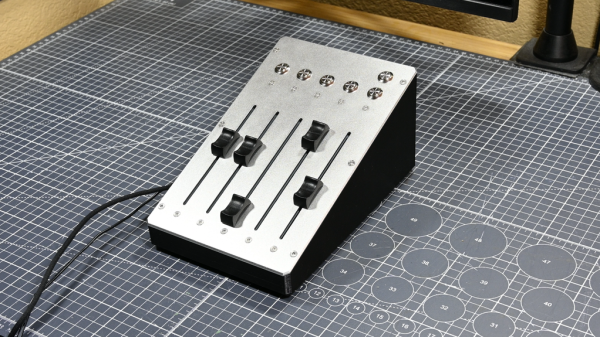

These days, Windows has a moderately robust method for managing the volume across several applications. The only problem is that the controls for this are usually buried away. [CHWTT] found a way to make life easier by creating a physical mixer to handle volume levels instead.

The build relies on a piece of software called MIDI Mixer. It’s designed to control the volume levels of any application or audio device on a Windows system, and responds to MIDI commands. To suit this setup, [CHWTT] built a physical device to send the requisite MIDI commands to vary volume levels as desired. The build runs on an Arduino Micro. It’s set up to work with five motorized faders which are sold as replacements for the Behringer X32 mixer, which makes them very cheap to source. The motorized faders are driven by L293D motor controllers. There are also six additional push-buttons hooked up as well. The Micro reads the faders and sends the requisite MIDI commands to the attached PC over USB, and also moves the faders to different presets when commanded by the buttons.

If you’re a streamer, or just someone that often has multiple audio sources open at once, you might find a build like this remarkably useful. The use of motorized faders is a nice touch, too, easily allowing various presets to be recalled for different use cases.

We love seeing a build that goes to the effort to include motorized faders, there’s just something elegant and responsive about them. Continue reading “Motorized Faders Make An Awesome Volume Mixer For Your PC”