Making a truly flat surface is a modern engineering feat, and not a small one. Even making something straight without reference tools that are already straight is a challenge. However, the ancient Egyptians apparently made very straight, very flat stone work. How did they do it? Probably not alien-supplied CNC machines. [IntoTheMap] explains why it is important and how they may have done it in a recent video you can see below.

The first step is to define flatness, and modern mechanical engineers have taken care of that. If you use 3D printers, you know how hard it is to even get your bed and nozzle “flat” with respect to each other. You’ll almost always have at least a 100 micron variation in the bed distances. The video shows how different levels of flatness require different measurement techniques.

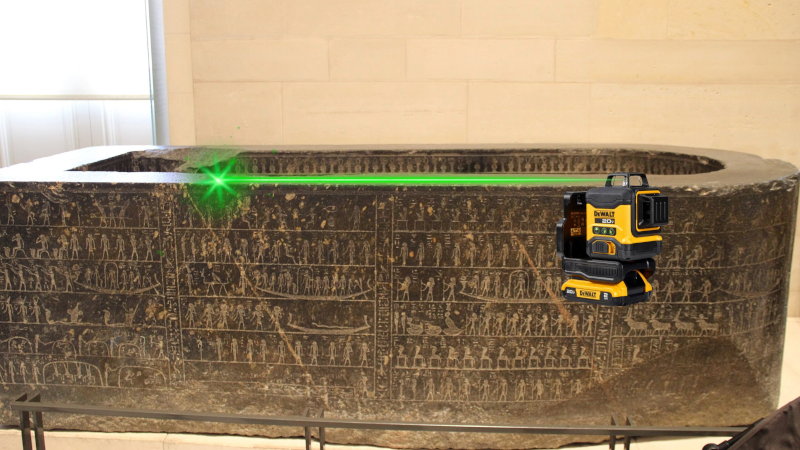

The Great Pyramid’s casing stones have joints measuring 0.5 mm, which is incredible to achieve on such large stones with no modern tools. A stone box in the Pyramid of Seostris II is especially well done and extremely flat, although we can make things flatter today.

The main problem with creating a flat surface is that to do a good job, you need some flat things to start with. However, there is a method from the 19th century that uses three plates and multiple lapping steps to create three very flat plates. In modern times, we use a blue material to indicate raised areas, much as a dentist makes you chomp on a piece of paper to place a crown. There are traces of red ochre on Egyptian stonework that probably served the same purpose.

Lapping large pieces is still a challenge, but moving giant stones at scale appears to have been a solved problem for the Egyptians. Was this the method they used? We don’t know, of course. But it certainly makes sense.

It would be a long time before modern people could make things as flat. While we can do even better now, we also have better measuring tools.

I’m not saying it was aliens.

…but it was aliens.

Oh come on, someone had to say it.

“I am an individual. I am not part of a herd. I am an individual. I am not part of a herd.”

i hear ya

Much like you didn’t have to reply with your nonsense.

Thass raciss’.

To those of us who are not Egyptian it was aliens.

It was the three plate method, and it’s extremely old. Much older than the 19th century.

That blue stuff is called Prussian blue. The tricky part there, and maybe someone more machine shop oriented than me can correct me is, you still need a reference flat.

It’s hard to think about ancient processes that could afford a flat surface being honest. All I can think of is a large vat of water or oil

Assuming the meniscus was flat enough. half the challenge there would be ensuring whatever was dropped on it was dropped true.

Fun to think about.

That blue stuff is indeed called a lot of things, including Prussian Blue, as it was at one point made with actual Prussian Blue (the chemical/dye) suspended in oil. But the modern formulations, even if they’re called “prussian blue”, are usually made with other dyes or pigments (most commonly gentian violet, I believe, just to be confusing).

In the circles I know, it’s usually referred to as “dykem”, which is a brand that essentially became the kleenex of blue marking dyes.

Dykem is different in that it dries. The ink used for flattening is not dry. Today, artist oil colors or products like that are used. The idea is you want a thin film that can transfer from one surface to another indicating highs and lows. Most common reference is the granite or cast iron surface plate which is used to check cast iron straight edges and other tolls that fit the work. Normally shops buy surface plates and have them verified by traceable standards but you could lap flat using the three plate method which is self proving.

Okay I had an idea. If you had a fat and a big pool of water. You could make one side flat by letting it solidify on top of a tub of water if you were very careful

Well, the water must not move and it would be hard to stabilize the fat once it is removed from the water. Incidentally, float glass which is pretty flat is made by pouring molten glass on a tank of molten tin. The tough thing about references is that they are usually tied to a standard temperature of 68 degrees F, they must also be pretty resistant to changing shape which is why granite and cast iron are popular. For a home shop, a great “pretty close” reference is a large thick tile or a cutout from a granite sink. Those are roughly close enough.

Float glass is great but it definitely is a product of a different era. Cool to know about the tiles.

I think you could pour hot butter or coconut oil as a liquid into warm water and wait for it to rise and solidify and get a mostly undisturbed fat puck. I think the downside is it’s material properties. Especially in a desert

Surface tension says ‘hi’.

Wouldn’t even start flat.

Perhaps if you select a fat w very similar surface tension to water, altered the waters surface tension or both.

But results would still suck.

Chinese surface plates are reasonably priced and are ‘close enough’ for most purposes.

As noted, glass is good enough for most purposes.

“All I can think of is a large vat of water or oil” Ice.

Or molten lead. It should solidify pretty flat.

It’s have slag though. All the metal casting I’ve seen makes rough ingots unless they get cncd

There are a very few metal alloys that’ll solidify more or less flat, but lead definitely isn’t one, because it thermally contracts as it cools, and since it starts solidifying at the outside where it’s in contact with the mold, you get a conic surface on the top. It doesn’t sink as much as eg aluminum, because it melts at a lower temperature, but it’s still pretty significant.

Am I the only one who associates Prussian Blue and cyanide?

Are you thinking of Paris Green and arsenic?

No, but I did see that episode of Doc Martin. Typically, iron(II) sulfate is added to a solution suspected of containing cyanide, such as the filtrate from the sodium fusion test. The resulting mixture is acidified with mineral acid. The formation of Prussian blue is a positive result for cyanide.

Are you thinking of Prussic Acid?

No. Typically, iron(II) sulfate is added to a solution suspected of containing cyanide, such as the filtrate from the sodium fusion test. The resulting mixture is acidified with mineral acid. The formation of Prussian blue is a positive result for cyanide. In Perry Mason, prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide) is a frequently used poison in early, black-and-white episodes, often appearing as a lethal substance disguised in drinks or food, such as in “The Case of the Lonely Heiress”. It is characterized as a fast-acting poison that causes immediate death.

Why lower a heavy object in a precise and repeatable manner when it can be propped up in a basin with a wide overflow and a little bit of constant water flow. With a few mm of water above the work, hollow cylinders put on the surface permit easy readout of the quieted meniscus on the inside, and the same setup provides the medium for lapping and slurry removal.

No reference needed. The three-plate method developed in the 1830s by Joseph Whitworth achieves flat with a few tools and considerable elbow grease. Gena Bazarko show how on his YT channel.

The “blue stuff” is only good at showing you how well part A meets part B – so you are right in general use you’d need a reference flat, or to check the fit on a tapered cone like the “morse taper 3” your mill spindle likely has you’ll need a reference version of the other side of that mating surface (which you can just use your mill spindle for in most cases) etc.

However if you have a big flatish surface and wish to compare it to any other flatish surfaces you can even if neither is really flat yet – as long as you are moving the flat surfaces over each other the blue will show the where contact is being made, and you can work on them both to make better more even contact – so while turning them into a convex/concave pair could be a problem (if you have only 2 similar sized references and are always checking them against each other in the same area that slight dish can end up being amplified so both parts fit wonderfully but only because they are matching curves) you can use that blue to improve you way to making your references.

I suspect given the materials the Egyptians were working with just the way they must have dragged the stones around probably works to flatten and smooth the cut stones in very similar way to the way you’d recondition your surface table or create other flats simply by the statistical action that the highest points tend to grind down first..

Dont you just need three flat surfaces lapping against each other to achieve very precise flatness. I’m sure these stones must have been hung with supports and lapped with abrasives. I mean they built the pyramids, why wouldn’t they be able to lift and fixture other crazy big stones?

You don’t need a flat to begin the process, but you need three surfaces.

It’s called the Whitworth three plates method, and with 2 plates you can get the surfaces to match, but they might be concave or convex (but the same, to a high degree of accuracy). When you go to three plates you can get optically flat surfaces.

https://ericweinhoffer.com/blog/2017/7/30/the-whitworth-three-plates-method

Thanks for the link this is really cool!

This is a mystery? Water lies perfectly flat (meniscus – compensated) when there is no pressure differential on the surface like on a calm day or within the wind protection of a tent. Trenches and troughs could distribute the flatness wherever needed, and strings could handle horizontal lines and plums with as much precision as one wants even with 4000 year old tech. The impressive part is that they had the will to go to that trouble. :-) If they could construct hoses they might not even need trenches.

Delicious plums.

huh. Fill the casket with water to the rim and eyeball the meniscus to get it less than 1mm. Actually sounds pretty easy.

No. Those were only used in Barbara Caves on India

This is barabar caves in India.

These are far more impressive that this Egyptian artefact for size and flatness… And still a mystery of human genius.

But it is more recent.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barabar_Caves

Moore’s Foundations of Mechanical Accuracy is a must-read.

Basically starting with nothing then flat, then right angles (yada yada I am

Hand waving ) now we have micron precise jig boring machines. All with historical lessons and in a very readable form.

Mica was once used as window material. How would it be as a reference flat?

At the end of the day, nobody can explain how they achieved such great feats of engineering with the tools they had. Aliens, by far, is the best possibility.