Last time I delivered on this column, I told you about the USPS’ attempts to fully automate a post office. Of course, that’s a bit of a misnomer, since it took 1,500 employees to actually operate the place on a daily basis. Although Project Turnkey in Rhode Island and Project Gateway in California were proving grounds for all kinds of mail sorting and processing equipment, the act of actually reading addresses and routing mail to its final destination still required human intervention and hand coding.

Today, the post office processes hundreds of millions of mail pieces each day using various pieces of equipment. One of those important pieces of equipment is the OCR address reader, which manages to make sense of all kinds of chicken scratch.

All Eyes On OCR

In their ever-increasing efforts to remove the human from the mail sorting operation, the USPS looked with a loving eye toward Optical Character Recognition, or OCR.

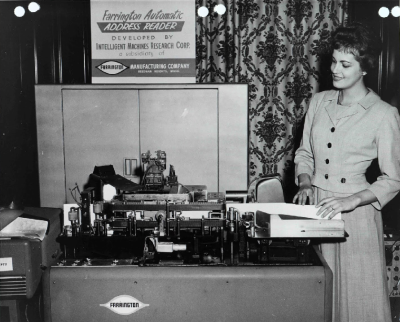

The post office was an early adopter of OCR, beginning their R&D in the 1950s. During this time, the Farrington Manufacturing Company began developing their Automatic Address Reader under contract with the USPS.

Within a few rounds of prototypes, this machine could recognize and register addresses almost anywhere on the face of the envelope, whether they were typed, handwritten, or imprinted, tightly-spaced or not, and whether the lines were flush or staggered. After confirming the addresses, the machine would sort the mail into various slots for local, long distance, and international destinations.

Although there were two ways for a machine to recognize characters — optical and magnetic — the optical way eventually won out. The optical operation employed photo-electric cells in order to sense the mail piece and then read the address. The magnetic method scanned for ink containing iron oxides. They both had their merits; although OCR had issues with lack of contrast and sometimes over-marking of addresses, it was ultimately the more practical choice.

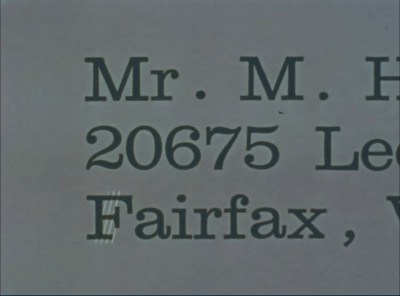

As you will see in the video below, OCR machines could read 42,000 addresses per hour by 1970 in an operation called Line Find. The machine performed three steps for each piece of mail. First, it finds either the last line (city and state) or the second-to-last line (street address) depending on whether the letter is local or outgoing, and then secondly it measures the height of the character. Finally, it reads the line.

As you will see in the video below, OCR machines could read 42,000 addresses per hour by 1970 in an operation called Line Find. The machine performed three steps for each piece of mail. First, it finds either the last line (city and state) or the second-to-last line (street address) depending on whether the letter is local or outgoing, and then secondly it measures the height of the character. Finally, it reads the line.

How does it do this? A CRT shoots a beam of light through an “expanding optical system” at the face of the envelope. The beam produces a raster, which scans from right to left until it finds the address block. Then it finds the leftmost character and stops. All of this happens in five thousandths of a second.

Then the raster changes to a finer scan and takes a look at the first letter in the line to determine it’s size. Based on this, the raster wastes no energy on blank space, adjusting to the height of the rest of the line. The optical system uses the characteristics of letters such as horizontal lines on the left and various curves and lines to the right to determine the letter. There’s a lot more to it than that, but I won’t spoil this short but informative video for you.

The Curse of Cursive

As you might imagine, the wild variations in people’s handwriting caused problems for OCR machines. But by analyzing the length and location of strokes, some handwriting could be analyzed. Today, OCR can read nearly everything — about 99% of addresses, even those written in tight or looping cursive. These days, if an address can’t be read by OCR, a picture gets sent to the Remote Encoding Center (REC) in Salt Lake City, UT for decoding by human eyes.

Indeed, the REC’s operations are so vital that they have three ISPs coming in on three fiber lines at different points for redundancy. There used to be dozens of RECs across the United States, but OCR has gotten so good that they only need the one center these days.

Even so, the REC handles 1.2 million mail pieces per day, requiring 7,150 keystrokes minimum per hour from each operator. That means they process one piece of mail every four seconds on average. So as you can see, the movement of mail requires human handling to this day.

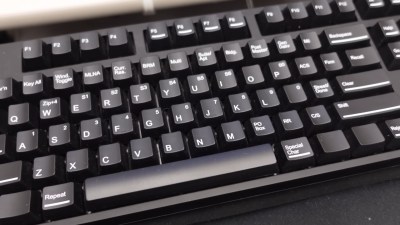

In the video below, Tom Scott takes a trip to the REC and learns how to read and encode mail so that it can move forward and be delivered. It’s an interesting process that requires a special keyboard with the numbers on the home row, and a host of modifiers and things in their place along the top.

First, unless it’s missing entirely, the C portion of the address (the ZIP code) is deciphered and coded, then outward portion of the address (city and state), and then the inward portion (the street address). The REC has every known good address in America sitting on their servers, and once they get a match, the plant that has the mail piece is notified immediately where to send it, and the piece moves forward. All of this for the low, price of 66 cents per ounce. Amazing, isn’t it?

But Wait, There’s More

Stay tuned for more about the USPS’ advancements, including ZIP codes, vending machines, and something called v-mail. We’ll also take a look at ways the USPS has attempted to improve productivity and service as well as the customer experience. And no, I haven’t forgotten about that bit of trivia that I promised.

Banks have moved to OCR to read cheques.

When a cheque was repeatedly rejected by the machine, I took it to the human, who helpfully suggested I could save time using the machine.

I explained the machine had failed to read it.

It turned out that the writing was so bad that the human could barely read it either. I had an advantage as I knew which invoice it was for so knew what it should say!

Interestingly, this wasn’t the first time the machine rejected a cheque for me. It seems that the kind of person who still writes cheques also can’t write legibly.

I had problems trying to deposit a check the other day: The reader picked up “VOID” from the “VOID AFTER 90 DAYS” line and thought that the check had been voided.

What does the second scanner do. My first thought was that it enables the device to read two envelopes at once but the video says that the envelope goes to the second scanner “after it has been read”.

I think they’re implying an interleaving scheme. Right before that, they say “To make most efficient use of the electronic reading and memory system….” — so I think maybe there’s two scanner heads (that read slower than the processor can process things), and the processor alternates between them, with the letters interleaved and spaced so that alternating letters end up in front of alternating scanners at the right times.

I wonder if that attempt at improving productivity we’re going to talk about happened in the 80’s, and if it has anything to do with the creation of the term “going postal”?

I had an uncle who worked with USPS about that time, and his experience led him to developing schizophrenia.

I wonder if a lot of the workers that went “postal” were Vietnam vets with PTSD issues.

As it was a government agency (at the time) it gave veterans a 10 point boost in its hiring exam.

This never stopped… still 10 point boost means they are nearly guaranteed to get the job they apply for if active duty… assuming they are relatively qualified.

IIRC there was an incident in the 1990s where a postal worker shot up their workplace. So “going postal” was coined as meaning “employee mental breakdown leading to workplace violence.”

There is technology used by ireland – eircode, which minimizes unnecessary letters in address. So for example you want to send a letter to

John Doe living in CONYNGHAM ROAD 14,DUBLIN 8 Ireland,

you just write

” John Doe, D08 FT5W ”

Thats it.

Google maps uses similar thing called “pluscodes” which are essentially geographic coordinates encoded in different way. So they are universal and global.

Wish we had shorthand addresses like this in US post. Occasionally we even add four numbers to our zip codes when we need to get real specific.

Long as it’s accurate. Google still can’t get my location right even after I told them.

Interesting, but how does the letter feature detector work?

I retired from the USPS a while back. Their OCR’s used to be separate machines that photographed, looked-up, sprayed a barcode, and sorted to about 55 separations. Now the stamp cancelling machines photograph, perform OCR on a series of blade servers locally (sending unreadable ones to SLC), and print the strange orange barcodes on the back of the piece. Trays of mail are tagged with the time they were read and are staged in automated storage units by time of initial reading. The storage units release the mail that has been read to Output SubSystem machines that: Read the unique orange barcode from the back of each piece, match it to the looked-up ZIP+4 (and last 2 digits of the street address) barcode, spray that barcode on the front, and then sort the letter into one of hundreds of stackers. Much less handling than in the past.

It is disheartening on several levels that all the quite remarkable development that led to the automatic sorting of mail is processing what am guessing must now be, like, 99.9% junk mail. Junk mail that no one actually opens.

It all seems so futile.