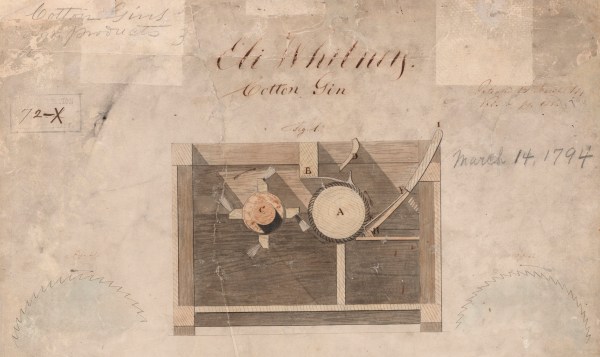

If you went to elementary school in the United States, you no doubt learned about Eli Whitney’s cotton gin as an example of how the industrial revolution took previously manual processes and replaced the low-efficiency of human labor with machines. The development of the cotton gin — patented in 1794 — involves an interesting lesson about solving engineering problems.

Farmers in the southern United States had a big problem. Tobacco was a cash crop, but it eventually left your fields barren and how to solve that problem wasn’t understood yet. Indigo was valuable for dye, but the British were eating away that market with indigo created in its colonies. Rice requires a lot of water and swamp, so it was only suitable for certain areas.

There was one thing that grew very readily in much of the land: cotton. Unfortunately, the cotton had little seeds you had to remove. A single person could clean — maybe — a pound of cotton a day. In the late 1700s, plantation owner Catharine Littlefield Greene introduced Whitney to a group of farmers were trying to decide if there was a way to make cotton a more profitable crop.