[Bunnie] has penned his thoughts on the new 25% tariffs coming to many goods shipped from China to the US. Living and working both in the US and China, [Bunnie] has a unique view of manufacturing and trade between the two countries. The creator of Novena and Chumby, he’s also written the definitive guide on Shenzen electronics.

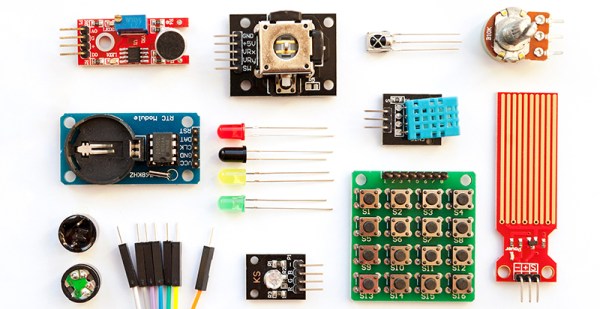

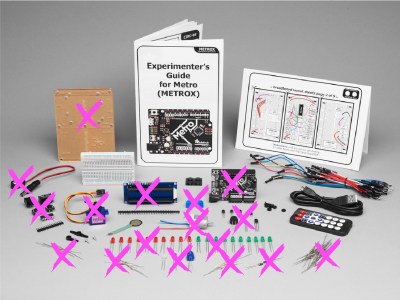

The new US tariffs come into effect on July 6th. We covered the issue last week, but Bunnie has gone in-depth and really illustrates how these taxes will have a terrible impact on the maker community. Components like LEDs, resistors, capacitors, and PCBs will be taxed at the new higher rate. On the flip side, Tariffs on many finished consumer goods such as cell phone will remain unchanged.

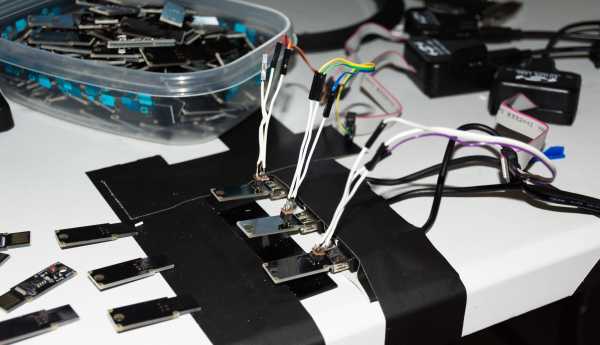

As [Bunnie] illustrates, this hurts small companies buying components. Startups buying subassemblies from China will be hit as well. Educators buying parts kits for their classes also face the tax hike. Who won’t be impacted? Companies building finished goods. If the last screw of your device is installed in China, there is no tax. If it is installed in the USA, then you’ll pay 25% more on your Bill of Materials (BOM). This incentivizes moving assembly offshore.

What will be the end result of all these changes? [Bunnie] takes a note from Brazil’s history with a look at a PC ISA network card. With DIP chips and all through-hole discrete components, it looks like a typical 80’s design. As it turns out the card was made in 1992. Brazil had similar protectionist tariffs on high-tech goods back in the 1980’s. As a result, they lagged behind the rest of the world in technology. [Bunnie] hopes these new tariffs don’t cause the same thing to happen to America.

What will be the end result of all these changes? [Bunnie] takes a note from Brazil’s history with a look at a PC ISA network card. With DIP chips and all through-hole discrete components, it looks like a typical 80’s design. As it turns out the card was made in 1992. Brazil had similar protectionist tariffs on high-tech goods back in the 1980’s. As a result, they lagged behind the rest of the world in technology. [Bunnie] hopes these new tariffs don’t cause the same thing to happen to America.

[Thanks to [Robert] and [Christian] for sending this in]