Automotive security specialist by day [P1kachu] hacks his own cars as a hobby in his free time. He recently began to delve into the Engine Control Units (ECUs) of the two old Hondas that he uses to get around in Japan. Both the 1996 Integra and the 1993 Civic have similar engines but different ECU hardware. Making things more interesting; each one has a tuned EPROM, the Civic’s being of completely unknown origin.

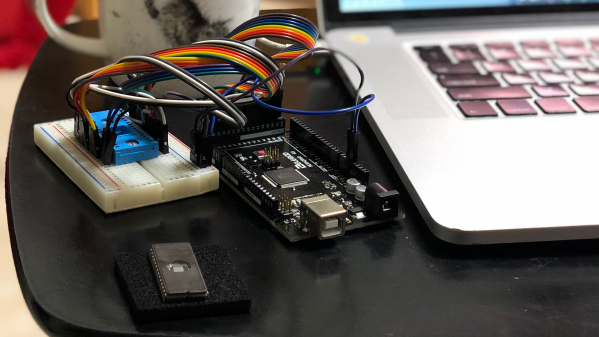

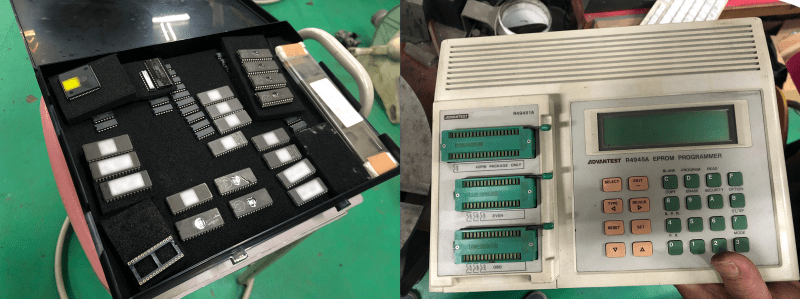

[P1kachu] took his Civic to a shop to have some burned-out transistors replaced in the ECU, and a chance conversation with the proprietor [Tuner-san] sends him on a journey into the world of old EPROMs. [Tuner-san] pulled out an old PROM duplicator stashed away under the counter which he originally used as a kid to copy PROM chips from console games like the Famicom. These days he uses it to maintain a backup collection of old ECU chips from cars he has worked on. This tweaked [P1kachu]’s curiosity, and he wondered if he could obtain the contents of the Civic’s mysterious PROM. After a false start trying to use the serial port on the back of the PROM copier, he brute-forces it. A few minutes of Googling reveals the ASCII pinout of the 27C256 EPROM, and he whips out an Arduino Mega and wires it up to the chip and is off and running.

He’s currently digging into the firmware, using IDA and a custom disassembler he wrote for the Mitsubishi M7700 family of MCUs. He started a GitHub repository for this effort, and eventually hopes to identify what has been tweaked on this mysterious ECU chip compared to factory stock. He also wants to perform a little tuning himself. We look forward to more updates as [P1kachu] posts the results of his reverse engineering efforts. We also recommend that you be like [P1kachu] and carry an Arduino, a breadboard, and some hookup wire with you at all times — you never know when they might come in handy. Be sure to checkout our articles about his old Subaru hacks from in 2018 if these kinds of projects interest you.