When purchasing high-end gear, it’s not uncommon for manufacturers to include a little swag in the box. It makes the customer feel a bit better about the amount of money that just left their wallet, and it’s a great way for the manufacturer to build some brand loyalty and perhaps even get their logo out into the public. What’s not expected, though, is for the swag to be the only thing in the box. That’s what a Redditor reported after a recent purchase of an Nvidia GeForce RTX 5090, a GPU that lists for $1,999 but is so in-demand that it’s unobtainium at anything south of $2,600. When the factory-sealed box was opened, the Redditor found it stuffed with two cheap backpacks instead of the card. To add insult to injury, the bags didn’t even sport an Nvidia logo.

The purchase was made at a Micro Center in Santa Clara, California, and an investigation by the store revealed 31 other cards had been similarly tampered with, although no word on what they contained in lieu of the intended hardware. The fact that the boxes were apparently sealed at the factory with authentic anti-tamper tape seems to suggest the substitutions happened very high in the supply chain, possibly even at the end of the assembly line. It’s a little hard to imagine how a factory worker was able to smuggle 32 high-end graphics cards out of the building, so maybe the crime occurred lower down in the supply chain by someone with access to factory seals. Either way, the thief or thieves ended up with almost $100,000 worth of hardware, and with that kind of incentive, this kind of thing will likely happen again. Keep your wits about you when you make a purchase like this.

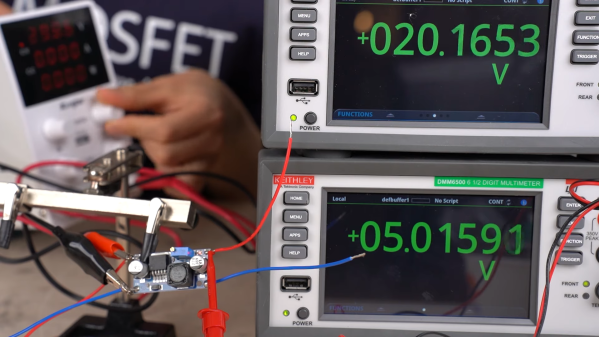

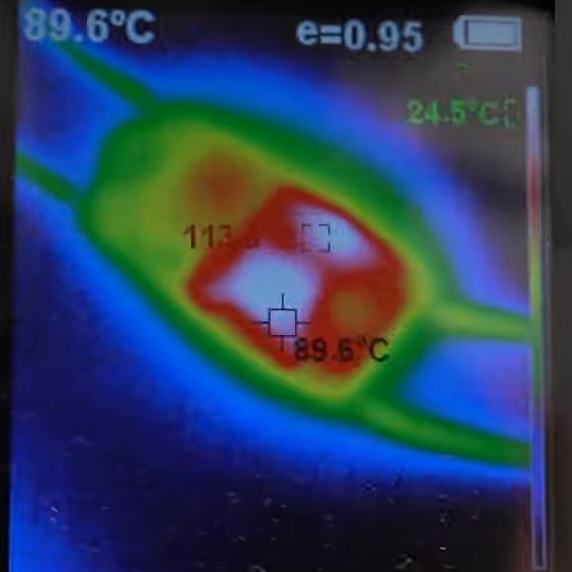

Or do you? It’s not so clear after watching [Denki Otaku]’s video on a bargain bag of buck converters he got from Amazon — ¥1,290 for a lot of ten, or $0.85 a piece. The thing that got [Denki]’s Spidey senses tingling is the chip around which these boards were built: the LM2596. These aren’t especially cheap chips; Mouser lists them for about $5.00 each in a reel of 500.

Or do you? It’s not so clear after watching [Denki Otaku]’s video on a bargain bag of buck converters he got from Amazon — ¥1,290 for a lot of ten, or $0.85 a piece. The thing that got [Denki]’s Spidey senses tingling is the chip around which these boards were built: the LM2596. These aren’t especially cheap chips; Mouser lists them for about $5.00 each in a reel of 500.

A

A