Do you know how a film projector works? We thought we did, but [Bill Hammack] made us think twice. We have covered the Engineer Guy’s incredibly informative videos many times in the past, and for good reason. He not only has a knack for clear explanation, the dulcet tones of his delivery are hypnotically soothing. In [Bill]’s latest video, he tears down a 1979 Bell & Howell 16mm projector to probe its inner workings.

Movies operate on the persistence of vision (POV) principle, which basically states that the human brain creates the illusion of motion from still images. If you’ve ever drawn circles and figure eights in the nighttime air with a sparkler or perused a flip book, then you’ve experimented with POV.

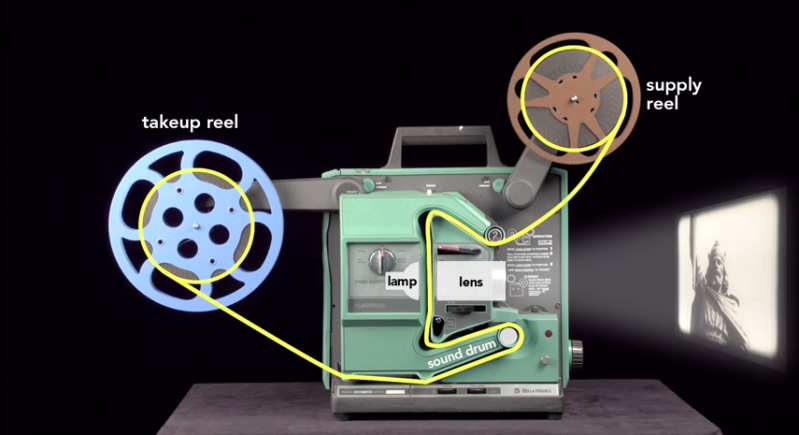

A film projector is no different in theory. Still images on a strip of celluloid are passed between a lamp and a lens, which project the images on to a screen. A device called a shuttle advances the film by engaging its teeth into the holes on the edge of the film and moving downward, pulling the film with it. The shuttle then disengages its teeth and moves up and forward, starting the process again.

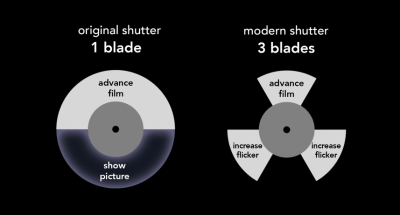

Film is projected at a rate of 24 frames per second, which is sufficient to create the POV illusion. A projector’s shutter inserts itself between the lamp and the lens, blocking the light to prevent projection of the film’s physical movement. But these short periods of darkness, or flicker, present a problem. Originally, shutters were made in the shape of a semi-circle, so they block the light half of the time. Someone figured out that increasing the flicker rate to 60-70 times per second would have the effect of constant brightness. And so the modern shutter has three blades: one blocks projection of the film’s movement, and the other two simply increase flicker.

Film is projected at a rate of 24 frames per second, which is sufficient to create the POV illusion. A projector’s shutter inserts itself between the lamp and the lens, blocking the light to prevent projection of the film’s physical movement. But these short periods of darkness, or flicker, present a problem. Originally, shutters were made in the shape of a semi-circle, so they block the light half of the time. Someone figured out that increasing the flicker rate to 60-70 times per second would have the effect of constant brightness. And so the modern shutter has three blades: one blocks projection of the film’s movement, and the other two simply increase flicker.

[Bill] explains how the projector reads the optical soundtrack. He also delves into the mechanisms that allow continuous sound playback alongside intermittent projection of the image frames. You’ll never look at a projector the same way again.

Want to know more about optical soundtracks? Check out this Retrotechtacular that explores the subject in detail.

Thanks for the tip, [Sean].

pfft, arthur the aardvark covered this years ago.

I’ve got a very old projector (when there was no sound on the films), and it uses a classic “Malta cross” system to drive the film advance. The shutter is then only one quarter of the circle (and is curiously placed between the lens and the screen). Meanwhile, old cameras used only 16 or 18 fps, and that’s not enough to avoid a sensible flicker…

That’s an interesting thing, because the three lobed shutter has the same 1:1 duty cycle as the half-circle, which means the two are equally bright – but if only one of the lobes, a quarter in your case, was actually blinded then the duty cycle would be 2:1 or 3:1 which makes the picture brighter and the dark period shorter.

At some point, the dark flash must become too short to notice regardless of the flicker rate because eyes detect a light coming on faster than a light going off. You get a physical after-image in the retina that isn’t dependent on the brain’s interpretation of the view.

CRTs flickered badly because they were scanning and each pixel was actually “off” and slowly decaying in brightness for far longer than it was “on”, but in a film projector with the quarter lobe, the picture is on for much longer than it is off.

Modern LCD monitors actually strobe their backlights between frames in order to “insert dark frames” so you wouldn’t notice the ghosting and motion blurring as they transition between images. You just see the after-image of the previous frame.

The CRT refresh illustrated:

http://www.drhdmi.eu/images/Refresh_scan.jpg

By the time the scanline got to the bottom of the screen, the top of the screen was already black, so the CRT tube relied entirely on the persistence of vision to work at all. A 60 Hz tube would take about 10-15 milliseconds to scan from top to bottom, and most of the screen would remain dark for most of the time, yet the picture didn’t appear to waver at all. You could see the flicker by the corner of your eye, but not by looking straight at it.

A film projector showing a 16 fps film with a quarter disc shutter will display a single frame for 62.5 milliseconds, of which only 15.6 ms is dark. Comparable to the persistence of vision required to view the CRT. The motion may be jerky, but not because of the flicker, which would have been mostly imperceptible.

I worked as an assistant projectionist in the 90’s, The 35mm projectors used “matla crosses”.

The loop at the top was not as important as the bottom loop. When threading up, getting that one too small could easily break the film (and give small errors in sound sync).

16 mm Bell and Howell now only showing half height of picture. Can adjust frame adjustment but still only shows top half or bottom half of frame

My aunt had some old Our Gang reels for home use. Nice shape, but no audio…silent movie type stuff to keep kids occupied.

Never leave your bored nephew, his erector set, and a bit of toolage nearby….I built a somewhat workable projector from some parts I found. I knew nothing about gate speed regulation, but it worked mostly. Not a bad job for a 9 year old.

unfortunately, I took it apart to build something else. Cest La hacke!

Ah you forgot the most important part of any projector, the intermittent. The intermittent is the gearbox that stops the film when light is passed through the shutter. Without it, or if it’s out of sync with the shutter, the projected image will streak.

This is also the culprit when the projected image appears to shake, or bounce on the screen.

Good video on the mechanics of film projection. While some have mentioned the video not explaining maltese crosses or intermittent movements, all should realize that there were at least a few dozen different manufacturers of projectors for various gauges of film, and while all the projectors generally did the same thing, their design and operation could vary quite a bit. Some had pull down claws, some had intermittent moments. There were patent lawsuits regarding these designs since day one of motion pictures. The video described the “original shutter” as having 1 blade and the modern shutter having 3. When I had my projectionist job in 2000, I was operating eight modern Christie 35mm projectors that still had a just a single blade, and seven older Simplex projectors with triple blades. However the single blade on the Christie’s spun 3 times as fast, providing the same effect. There was a Century projector called a “JJ” that I never operated, but apparently it had more blades coming from opposite directions, making the image even less flickery, but requiring a brighter lamp house. I also worked at a drive in. There we had two bladed shutters, probably because we were trying to squeeze every lumen we could out of those projectors because they had thick lenses and long throws. Sometimes the gears lived in oil baths, sometimes you had to lube them every night. With movie theatre projectors, you could mix and match brands to a certain extent. A Century soundhead could be bolted to a Simplex projector head and a Christie Lamphouse. This would change how it worked and how it was threaded, maintained, and repaired, but it still all worked.

Intermittent MOVEMENTS. Sorry. I also should mention that Telecine projectors, that is, projectors intended for NTSC television, had 5 bladed shutters. Using 3:2 pulldown – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three-two_pull_down – this number of blades made the 24fps film not flicker when recorded on a “30” fps video camera, and this is the way it was done until movie scanners were introduced. That’s the main reason why home made movie transfers and bootleg “camcorder in the theatre” videos usually look so bad. The scanning of the camera catches the moments the screen is dark, and the image flickers. An earlier post mentioned flicker on “silent” speed films, that is, movies made at 16 or 18 frames per second. Years ago I discovered a way to minimize that flicker when making videos. If you get a hold of a projector that could vary the speed using a potentiometer, rather than a switch with a resistor ( or just wire one to the motor yourself) you could slow the film down to 15 fps, getting close to using two video frames for every single film frame. It wasn’t perfect but if you were just dealing with silent home movies it was pretty acceptable.

Hello!

this is wonderful –

I’ve watched/listened closely…

without troubling you too much sir – in bullet point form, can you please suggest why the Bell & Howell Super 8mm

might be making my film ‘jump’?

• shuttle problem?

• loop problem(s)

• shutter issue

• axel?

the film itself appears to be in excellent condition.

THANK YOU!!!!!

sincerely,

Marie Minas

p.s. or perhaps, as craiger222 says:

could my film picture be jumping due to the “intermittent”???

T H A N K Y O U!

Marie M.