This is the second in a two-part series looking at safety when experimenting with mains-voltage electronic equipment, including the voltages you might find derived from a mains supply but not extending to multi-kilovolt EHT except in passing. In the first part we looked at the safety aspects of your bench, protecting yourself from the mains supply, ensuring your tools and instruments are adequate for the voltages in hand, and finally with your mental approach to a piece of high-voltage equipment.

The mental part is the hard part, because that involves knowing a lot about the inner life of the mains-voltage design. So in this second article on mains voltages, we’ll look into where the higher voltages live inside consumer electronics.

The Power Supply

When the mains supply enters a piece of equipment, unless it is a very simple device such as an electric kettle that uses the mains-voltage AC as-is, it’s going to do something to that AC to turn it into more useful voltages. We’ll now consider the most common types of mains power supply you may encounter when you open a piece of equipment, to aid you in identifying where the hazardous circuits will lie.

Look at where the power enters the device. If it passes straight into a transformer from which a low voltage is derived, then you have little to worry about except for any fuses or switch components on the mains side of the transformer which you will have to avoid when powered up. If the low-voltage side is at a battery-equivalent voltage, then the rest of the electronics that derive their power from it can be treated as though they were battery-powered. They are at a low voltage and isolated from the mains, you can safely work on them while they are powered up.

It is however not always safe to assume that equipment with a transformer power supply will contain safe low voltages in the rest of its circuit. If for example your tastes run to vintage tube-based equipment then you’ll find several-hundred-volt HT supplies which though they will be isolated from the mains by the transformer should still be considered as just as dangerous as the mains supply.

In previous decades it was the norm for mains power to be converted to low voltage in an iron-cored transformer. More recent equipment though is more likely to use a switch-mode power supply in which the AC mains is rectified to a high DC voltage and sent through a much smaller and lighter ferrite-cored transformer at a much higher frequency. Switch-mode power supplies are lightweight and efficient, but from the point of view of this article they introduce more hazards as they contain significant mains-derived DC voltages.

The output side of a switch-mode power supply is isolated from the mains by the transformer and at a low voltage and thus safe to work on. The mains side will contain both a reservoir capacitor with a high DC voltage and a heatsink for the switching transistor which will be at a high voltage. If you look at the PCB of a well-designed switch-mode power supply it should have a clear demarkation between its high and low voltage sides, with a safe boundary distance between the two sides bridged only by the transformer and an optocoupler or small transformer for feedback. Unfortunately though not all such power supplies are so well designed and you may even find ones that would fail the most basic safety tests.

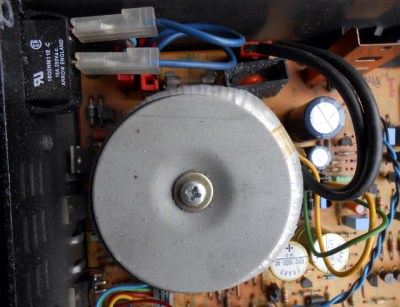

The good news is that switch-mode supplies are often off-the-shelf items that occupy their own circuit board, so any low-voltage logic boards they supply will be isolated from the mains and thus safe to work on while powered up. In the mid-2000s set-top-box picture above it is only the brown board that contains mains voltage, the green logic board is entirely low-voltage and safe to work on.

There is a third type of mains-derived power supply that you may occasionally encounter, one in which the mains is rectified directly to high-voltage DC and any lower voltages are derived without a transformer either through a regulator circuit or a potential divider. Some LED light bulbs, older CRT TV sets, and some older tube radios get their power this way, for example.

You especially need to be aware if you are working on this type of equipment, because every part of its circuit has to be considered to be at mains potential when it is powered up. You will see TV sets powered in this way referred to as “Live chassis”, and you will often find warning labels on their back covers or on the chassis itself. Any equipment that uses this power supply set-up will have extra insulation, and probably very few, well-insulated, external connections.

Exaggerated Caution

Now that you’ve identified what parts of your piece of equipment are live, you can tailor how you approach working on it with respect to high voltage safety.

If your interest lies only with low voltage parts of an item in which the live parts of the power supply are clearly separate and the power supply is an isolating one, then your job is easy, simply take extreme care to avoid touching those high voltage parts, exercise caution while it is powered up, and work on the low voltage parts as you normally would. The fuses next to the toroidal transformer or the brown switch-mode power supply PCB in the set-top-boxes pictured here should be avoided but you can prod away at will on their the low-voltage sides with your multimeter.

If however the piece of equipment you are working on is live at the point you are working on it, perhaps a switch-mode power supply or a live-chassis TV set, you will have to take a different tack. It is best to describe the approach you should be taking as “exaggerated caution”. Try to keep the device unplugged as much of the time as possible. Set up your probes for a measurement with the device unplugged, and only power it up to make a measurement or observation before powering it down again. It was not uncommon for TV repair engineers to work on live chassis sets with one hand behind their back, to avoid the possibility of a hand-to-hand shock.

Even unplugging the device is not foolproof. It is worth remembering that significant charge may remain in any large electrolytic capacitors in a piece of high-voltage equipment after its power has been removed. If you are examining these circuits when you have powered them down it is important to discharge these capacitors safely beforehand to avoid a shock. It is suggested that you always check for any charge remaining in a capacitor with your multimeter, and though you can spectacularly discharge them with a screwdriver across their terminals it is probably a bit safer to do so through a resistor connected to a set of test probes. Measure the voltage to ensure that the capacitor has safely discharged, and be prepared for a surprise as with some capacitors the voltage will return after discharge due to an unwanted property of large electrolytics. Repeat the discharge until the voltage is gone.

Really High Voltages

![The interior of a Mac Plus, showing the red EHT lead and insulating cup on the side of the CRT. Blake Patterson, [CC BY 2.0 ], via Wikimedia Commons](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/cathode_ray_tube_inside_a_macintosh_plus.jpg?w=400)

It is important to state immediately that the final anode voltage on a CRT is likely to be somewhere over 20 KV depending on the tube, and can be considered not merely dangerous but lethal. The glass funnel behind the screen of a CRT forms the reservoir capacitor for this EHT power supply, and can hold that 20 KV charge for long after the TV or monitor has been powered down. So you have to treat these devices with a lot of respect, for they can kill you.

That said, this should not stop you working on a device with a CRT in it. The designers of CRT circuits were aware of the hazards, and made sure that those EHT voltages were safely locked away where they were very difficult to touch. Take a look at the picture above showing the monitor components of a Mac Plus, the EHT circuit is the red cable and big round red sucker on the side of the CRT in the foreground. All the high voltage is safely contained behind that red insulation, and if you do not attempt to remove that connector from the side of the CRT it will remain there in a perfectly safe condition while you look at the other parts of the device.

In the unlikely event that you find yourself needing to remove a monitor or TV chassis from its CRT it is quite straightforward to discharge the CRT anode capacitor, however it is a procedure that must be performed with some care. Your aim is to discharge that anode connector to the black outer coating of the tube, known as the aquadag. To do this you will need to find a large flat-blade screwdriver with the thickest plastic handle you can. That handle is going to protect you from over 20KV for a short time.

You will need to connect the metal part of the screwdriver with a piece of insulated wire to the earth connection to the tube which is normally somewhere on the metal band that goes round the edge of its face. This is probably best achieved with crocodile clips on the end of your piece of wire. Then you simply hold the screwdriver by its plastic handle, and gently slide its tip under the rubber sucker covering the anode connector until you hear the “crack!” sound of it discharging. Then to ensure it’s really discharged, wait a few minutes and repeat the procedure, repeating it again after you’ve removed the connector. (Images from [Ax0n]’ CRT tutorial.)

Wrapup

The aim of these articles has not been to cover every possible electrical hazard in minute detail, but to equip you with some of the caution required and some of the skills to assess what risks lie in front of you when you open up a piece of high voltage equipment. However it is important to bear in mind that the decisions lie with you There is no dishonour in deciding that the risk in front of you is too great and backing away. Indeed it is healthy caution that keeps engineers alive to collect their pensions. We hope though that when you do decide to proceed with a piece of mains-powered kit, at least you too will now have a better chance of making it that far. Good luck!

This has been a really good series. I am thankful that when I first embarked on this kind of thing, I benefited from solid safety advice from experienced techs who were teaching me their tricks. I have lost interest in working on CRT’s and can rarely find a good reason to fool with a switching supply. Just buy a new one and scavenge parts from the old one. I did have good luck recently with a microwave oven repair. That can most definitely kill you, but falls outside the “mains voltage” realm of the current series. The stories in the follow ups have been especially good.

missed opportunity to legitimately title something “electric boogaloo”

good article though :D

How does the plastic on the screwdriver protect you? If you don’t hold the wire in one hand and the screwdriver in the other you would be ok right? From what I gather high frequencies and very high voltage don’t care about insulators. Obviously you shouldn’t play with things you don’t understand but how do you come to understand them fully without working with them?

Was it Nikola’s rule work with the left hand in the pocket, and use the right to manipulate?

Technically you are correct. If the screwdriver is properly grounded via the wire you attached then the 20KV from the TV would have no motivation to go through you; you would be fine without the insulation. This is not due to frequency in any way which is, in turn, related to capacitance… it is only due to your large body resistance vs the very low resistance of the wire. In the tv scenario above, we are discharging a capacitor so this implies DC….again, frequency doesn’t come into play here.

In reality, there could easily be a scenario where you forget to attach the ground wire to the screwdriver or the wire comes unclipped. In this case you better hope the screwdriver has an insulated handle. The insulation *should* stop arcs up to around 20 or 30kv. Again, nothing to do with frequency.

If you are working with high frequency, the screwdriver insulation would likely still be fine. The screwdriver metal – handle – hand capacitor formed has such a low value of capacitance you would need an incredibly high frequency signal to pass through it. I’ll leave research of capacitor displacement current and it’s effects on insulator materials up to you.

No mention of dielectric absorption, a.k.a. soakage? It is a very real phenomenon in which a disconnected capacitor can appear to “generate” a charge and voltage. Nasty with H.T. circuits!

One of my professors at UNC Charlotte, Dr, Robert Coleman (Now Emeritus faculty and retired) told a story of when he was a student they had a few industry donated large capacitors that stood a few feet high and had a strap that grounded the terminals to dissipate dielectric absorption. Well the straps were often left off… and he occasioned to sit on the capacitor being a very large capacitor it shocked the crap out of him! It left him with a good example of dielectric absorbtion too!

I think I’ve mentioned the need to repeatedly discharge more than once, take another look.

You did; my mistake. My poor excuse is that I’ve found it desirable to emphasise that to people, since they can “tune out” or speed read too much. (Just like me in this case, sigh)

Of course it isn’t restricted to electrolytics, e.g. CRTs.

Is there a simple explanation for how that happens? If there isn’t, don’t tell me the complicated one.

Simplicity is in the eye of the beholder. You can find a range of explanations at http://bfy.tw/5qMy

Real fuckin’ useful, thanks. “Let me google that for you”, that site’s still running, eh?

The effort you went to for your “joke”, you could’ve either said “I don’t know” or “I don’t feel like telling you”. Would’ve wasted less of both our time.

Another excellent article on one of my favorite topics. Thanks!

It is also wise to keep in mind that while the electric current might not kill you, what your body does while being shocked just might. I once witnessed an accident where a millwright working on the track of an overhead crane while standing on a man-lift about 12 meters above a concrete floor died. He took a 600VAC hit between his hand and his elbow, was flung off the stand, and died hitting the ground.

Ha ha! Once forgot to discharge a CRT I was replacing… Was carrying the CRT when my arm touched the contact. My arm moved instantly and the CRT went to the floor and BOOM! imploded. Nothing major happened, but I think the CRT implosion was probably more dangerous than the electric shock itself (the capacitance of the CRT is not that big, hence the shock, while painful is probably non lethal).

Lucky it missed your toe! That’s usually the worst part about getting zapped by a live CRT, dropping them on your toe

“The output side of a switch-mode power supply is isolated from the mains by the transformer and at a low voltage and thus safe to work on. ”

Unless the transformer insulation has failed, or the manufacturer cheaped out and used a non-isolating autotransformer design.

Isnt it standard to use a 1Mohm resistor between the screwdriver and the ground, so it doesnt arc and collapse the field instantly and blow the end of your probe off but collapse it gently?

Bearing in mind your resistor should be good to 30kv. Or 10x 100k resistors in series so eliminating the risk of arcing across a typical 1/4w resistor as theyre only rated to about 250v or so.

I’ve got a discharge probe set up, but I play a lot with old arcade machines with crt’s in them.

I never found it necessary. The capacitance of a CRT isn’t great enough to carry enough energy to blow the tip off of a screwdriver. Worked on TVs for many decades.

A FOAF story, probably mis-remembered from 40 years ago…

My first boss told of the story where he was fiddling with an HT supply (probably in a TV) using an appropriately long screwdriver with insulated shank. Then “ouch”. He investigated – and found an almost invisible oil track up the shank and onto the handle.

It is the things you don’t think of that come and bite you.

NEC might be ok with calling low voltage anything <50 but the IEC, like most sensible standards (e.g. to pick one at random, BS) regards 'low voltage' as up to 1000v. Isn't the US supposed to be a member of the IEC? Get with the times guys!!!

Not to say 50v is inherently safe anyway, try stripping insulation from a 50v supply with your teeth and see what happens.

The IEC standard (60038) is used in the context of power distribution installations, not consumer installations. In this standard, the difference between low and medium / high voltage is not whether the voltage can kill you, but whether it will arc readily over air gaps. Voltages that arc are not just dangerous when touched, but also when you come too close to a conductor.

Theoretically, any AC above 50V and sufficient power can kill you on contact.

A thing to note is that the easiest way to experience an “electric shock lite” is to touch something’s chassis while also touching the “safe” “low voltage” output of most any switching mode mains power supply (or shielding of a cable coming from another mains-powered appliance). That 5V USB charger and your PC’s chassis? ZAP! To be honest, I much prefer any amount of noise anywhere than that carefully placed suppression capacitor across the isolation transformer in mains switching supplies that single handedly defeats said isolation – well, it’s not a high-current path so it won’t actually kill you but it will absolutely get you to yell and curse. Remember, kids: this can and does happen between any two mains appliances (whip out your DMM and marvel at the typically 135V AC) whenever they happen to be plugged in just right (with non-polarised sockets), so that’s why you DON’T touch the F-plug while you disconnect cable from your PC’s tuner card (or the RCA leads going from your video card to your TV, or your USB hub’s power adapter) AND the chassis at the same time. All those are simply… electrifying!

For typical doubly insulated SMPS power brick, the output gorund will be at half the line voltage AC (double insulated SMPS typically derive EMI supression “ground” by capacitive divider from input pins), but it is reasonably weak that it does not matter.

Large SMPS that should be grounded (and thus have input and output grounds strapped together, most common example being PC power supplies) that somehow got the ground connection disconnected are another matter. And also another thing are large cable systems with their own ground like CATV, about 10 years ago I measured around 50mA (DC!) flowing between grounded DOCSIS modem chasis and the shielding of the CATV cable.

One of the things that are somehow missing from the article that even on the seemingly ELV side, there still could be things that generate surprisingly large and even dangerous voltages. For example you can get hole burned into your finger by CCFL power supply pretty easily and not even feel it happening.

How about a grid that is safe and open: https://github.com/OpenNanogrid/ON-draft – for playing with small DC devices, sourcing energy at home.. Not for connecting houses, power plants and big appliances as the large AC grid is a good choice for that.

Excellent article!

One thing that might be interesting: in a switching power supply, the recitified AC can be surprisingly high, up to 600VDC with a 230AC supply…

Wow. Very interesting article and comments. Thanks