It seems like every other day we hear about some hacker, tinkerer, maker, coder or one of the many other Do-It-Yourself engineer types getting their hands into a complex field once reserved to only a select few. Costs have come down, enabling common everyday folks to equip themselves with 3D printers, laser cutters, CNC mills and a host of other once very expensive pieces of equipment. Getting PCB boards made is literally dirt cheap, and there are more inexpensive Linux single board computers than we can keep track of these days. Combining the lowering hardware costs with the ever increasing wealth of knowledge available on the internet creates a perfect environment for DIYers to push into ever more specific scientific fields.

One of these fields is biomedical research. In labs across the world, you’ll find a host of different machines used to study and create biological and chemical compounds. These machines include DNA and protein synthesizers, mass spectrometers, UV spectrometers, lyophilizers, liquid chromatography machines, fraction collectors… I could go on and on.

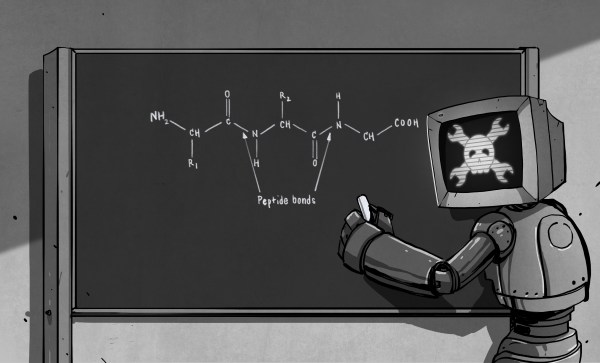

These machines are prohibitively expensive to the DIYer. But they don’t have to be. We have the ability to make these machines in our garages if we wanted to. So why aren’t we? One of the reasons we see very few biomedical hacks is because the chemistry knowledge needed to make and operate these machines is generally not in the typical DIYers toolbox. This is something that we believe needs to change, and we start today.

In this article, we’re going to go over how to convert basic chemical formulas, such as C9H804 (aspirin), into its molecular structure, and visa versa. Such knowledge might be elementary, but it is a requirement for anyone who wishes to get started in biomedical hacking, and a great starting point for the curious among us.