We don’t think of the human body as a piece of electronics, but a surprising amount of our bodies work on electricity. The heart is certainly one of these. When you think about it, it is pretty amazing. A pump the size of your fist that has an expected service life of nearly 100 years.

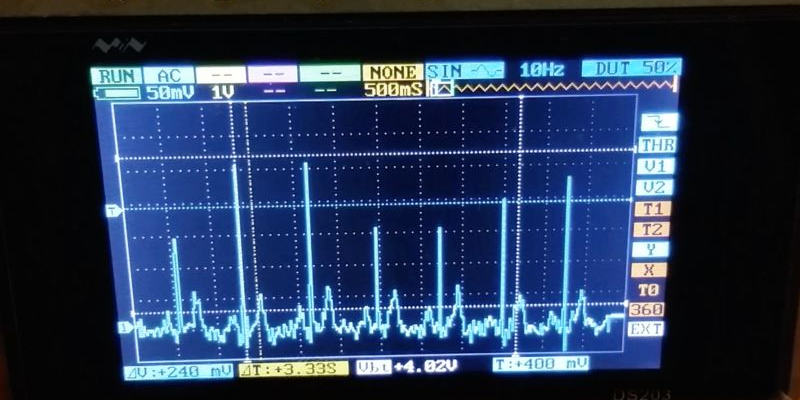

All that electrical activity is something you can monitor and–if you know what to look for–irregular patterns can tell you if everything is OK in there. [Ohoilett] is a graduate student in the biomedical field and he shares some simple circuits for reading electrocardiogram (ECG) data. You can see a video fo the results, below.

The design centers around an instrumentation amplifier which is ideal because it has a high input impedance and very high immunity to common mode noise. The simplest circuit is just an instrumentation amp and little else. The disadvantage is that it requires a bipolar power supply. [Ohoilett] also shows how you can add a few more parts to make the power supply simpler. In either case, an oscilloscope provides the output display (if you insist, there is a video on the page that shows the ECG connected to an Arduino).

If you want to know more about what to do with the data, you might enjoy this post. If you decide to get serious, you might check out the very robust open hardware project for ECG and other bioelectrical measurements.

Can you believe it is still rare for doctors to have hand held versions of these, and when they do there are single lead and it’s not possible to confidently exclude diagnosis’s.

Medicine is in some ways still very archaic. Nearly no one owns an electronic stethoscope. The entire trade is monopolized, Litmanns (stethoscopes), Welych-Allen (fundoscopes et c), 3M (anything that sticks to anything).

The problem is that everything needs to be certified. And the certification process is not easy, to begin with. But more problematic is that everyone and their dog has their own certification process and requirements.

And doctors do not have the time to check out which certifications are necessary for their work. So they generally just check what their closest-by hospital colleagues recommend, and buy that.

So on one side, the market is kind of monopolised by virtue of certification processes. And on the other side, newcomers on the market do not stand much of a chance, as doctors are really very, very conservative.

And by that, the medical community is cheating themselves out of cheaper devices that are just as reliable (if not more reliable, and especially easier to use and simpler to apply) than their old devices.

The medical community is _very_ conservative. Change is hard and slow and, as you mentioned, comes with a heavy certification burden. On one hand, this is a good thing — you really don’t want doctors “trying something new” out on you.

On the other, they’re slow. And superstitious. In the late 1990s, when “medical informatics” (read: collecting data) was becoming trendy, they came up with “results-based medicine” which is using statistics on the new data to figure out what actually works. This was a new field. In 1998. What had they been doing beforehand? Non-results-based medicine — small samples and word of mouth. This one doctor has a bunch of successes, and publishes, and others copy.

So yeah. Strange field. But the problem they have (fixing the human body) is like trying to fix the most complicated car you’ve ever seen without a shop manual, so you can cut them some slack too.

We have a manual… It’s just really tricky getting the patient to re-start once you turn it completely off…

That manual, it’s also constantly being re-written as we learn new things.

I don’t know that I’d say we’re very conservative. The big issue, in the US, is that the environment has dictated utterly insane technological marvels contained within hospitals, available to every patient immediately. US doctors train to this, and it is a little difficult to leave behind.

But, take that same doc, put him in an austere location, and they’re going to pick up anything they can to help out. I would have given quite a lot to have a hand held three lead, never mind a full blown 12-lead EKG. A handheld ultrasound… would have definitely saved pain, and probably lives. I’d use the hell out of this equipment. I can’t afford a $40,000 ultrasound machine, and I certainly can’t risk it in the environments I find myself in.

Ethically, there’s some serious issues here. Is it right, for me, as a provider, to endorse equipment that does not meet the highest level of certifications/standards? Personally, I already made my decision that when faced with a crisis, and the availability of a piece of equipment that is questionable in value but not questionable in safety, I’ll pick up the tool and make the best informed decision I can to alleviate my patient’s suffering.

Another problem is… unless you’ve had a cardio issue in the past week or have an active cardio issue, these guys are useless. My doctor has one, but doesn’t use it unless a person has/d signs of cardio issues.

And then there’s the ubiquitous malpractice lawsuit: “So, Dr. , knowing that you had a certified 12-lead ECG available and certified staff to use it, you chose to use this cut-rate, made-in-someone’s-backyard device on the deceased?”

I did not see any mention of safety in the article. With a direct connection to the human body, any leakage path could be deadly.

Someone noticed it in comments under the intructable. This thing is powered with 5V or 3.7V LiPo, is this really a threat?

Consider this possibility: What would happen if the input protection diodes of the instrumentation amplifier fail such that the electrodes now carry a 5v differential? The resulting circuit would be across the heart and the skin resistance would be minimized because the article used gel-electrodes.

Nothing would happen. 5V would do jack shit.

Someone noticed it in comments. But this is powered with 5V or 3.7V LiPo cell, can this voltage be any real threat?

If anyone is interested, look at body surface mapping of ECG. Its a tool to visualize the electrical excitation waves on a reconstructed surface of the heart. using a jacket of electrodes.

Super expensive when simple math would do. For nearly everything you need to make this help the diagnosis, it can be done using a 12-lead. The jacket is really expensive.

All you need is a 3D axis (x,y,z) of the vector of how the current is flowing. This changes with time, and so if you add time to the mix (x,y,z,t), basically that’s more than enough for 99% of the use cases of an ECG. The rest is like for specialized departments – like killing atrial fibrillations etc