When we mention vacuum technology, it’s not impossible that many of you will instantly turn your minds to vacuum tubes, and think about triodes, or pentodes. But while there is a lot to interest the curious in the electronics of yesteryear, they are not the only facet of vacuum technology that should capture your attention.

When [Alan Yates] gave his talk at the 2017 Hackaday Superconference entitled “Introduction To Vacuum Technology”, he was speaking in a much more literal sense. Instead of a technology that happens to use a vacuum, his subject was the technologies surrounding working with vacuums; examining the equipment and terminology surrounding them while remaining within the bounds of what is possible for the experimenter. You can watch it yourself below the break, or read on for our precis.

When [Alan Yates] gave his talk at the 2017 Hackaday Superconference entitled “Introduction To Vacuum Technology”, he was speaking in a much more literal sense. Instead of a technology that happens to use a vacuum, his subject was the technologies surrounding working with vacuums; examining the equipment and terminology surrounding them while remaining within the bounds of what is possible for the experimenter. You can watch it yourself below the break, or read on for our precis.

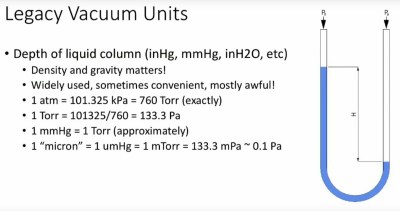

In the first instance, he introduces us to the concept of a vacuum, starting with the work of [Evangelista Torricelli] on mercury barometers in the 17th century Italy, and continuing to explain how pressure, and thus vacuum, is quantified. Along the way, he informs us that a Pascal can be explained in layman’s terms as roughly the pressure exerted by an American dollar bill on the hand of someone holding it, and introduces us to a few legacy units of vacuum measurement.

In classifying the different types of vacuum he starts with weak vacuum sources such as a domestic vacuum cleaner and goes on to say that the vacuum he’s dealing with is classified as medium, between 3kPa and 100mPa. Higher vacuum is beyond the capabilities of the equipment available outside high-end laboratories.

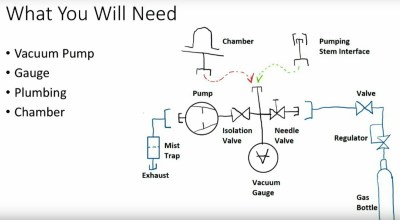

Introduction over, he starts on the subject of equipment with a quick word about safety, before giving an overview of the components a typical small-scale vacuum experimenter’s set-up. We see the different types of vacuum gauges, we’re introduced to two different types of service pumps for air conditioning engineers, and we learn about vacuum manifolds. Tips such as smelling the oil in a vacuum pump to assess its quality are mentioned, and how to make a simple mist trap for a cheaper pump. There is a fascinating description of the more exotic pumps for higher vacuums, even though these will be out of reach of the experimenter it is still of great interest to have some exposure to them. He takes us through vacuum chambers, with a warning against cheap bell jars not intended for vacuum use, but suggests that some preserving jars can make an adequate chamber.

Introduction over, he starts on the subject of equipment with a quick word about safety, before giving an overview of the components a typical small-scale vacuum experimenter’s set-up. We see the different types of vacuum gauges, we’re introduced to two different types of service pumps for air conditioning engineers, and we learn about vacuum manifolds. Tips such as smelling the oil in a vacuum pump to assess its quality are mentioned, and how to make a simple mist trap for a cheaper pump. There is a fascinating description of the more exotic pumps for higher vacuums, even though these will be out of reach of the experimenter it is still of great interest to have some exposure to them. He takes us through vacuum chambers, with a warning against cheap bell jars not intended for vacuum use, but suggests that some preserving jars can make an adequate chamber.

We are then introduced to home-made gas discharge tubes, showing us a home-made one that lights up simply by proximity to a high voltage source. Something as simple as one of the cheap Tesla coil kits to be found online can be enough to excite these tubes, giving a simple project for the vacuum experimenter that delivers quick results.

Finally, we’re taken through some of the tools and sundries of the vacuum experimenter, the different types of gas torches for glass work, and consumables such as vacuum grease. Some of them aren’t cheap, but notwithstanding those, he shows us that vacuum experiments can be made within a reasonable budget.

Grade A Overview / Primer. Will be looking for Alan’s other HaDs. For a geek, (us or him) he is a phun kinda guy! We may have to grow up, but we can still play with our toys or make them.

That’s the bloke who designed the HTC Vive!

My favorite vacuum technology is digital music. It runs on levels of 5 to 40 inches water. Playing original issue copyright songs from a century ago is right up in the air as the great airships before that Hitler and He thing caused a big bang.

Vacuums suck!

Ha!

As I understand it the positive pressure causes flow to lower pressure. The vacuum has no energy, therefore it cannot do shit. Just sit there and wait for energy. So sad really….

Actually, vacuum doesn’t suck.

Now, consider

Chamber A, has a nearly perfect vacuum. It is connected to chamber B with the help of a valve (V) in-between. Chamber B has a finite amount of air.

Consider the valve (V) is closed at the beginning of time.

If valve (V) is opened at instant ‘0’ , air in B will flow towards A

Therefore, in other words,

The vacuum in A will SUCK the air from B

Hence,

Vacuum SUCKS

Disclaimer:

The above text wah just for fun. Please Do not find any personal interest in it. I shall not be held accountable for any unforeseen consequences

Love the disclaimer…but….Chamber B is at a higher pressure (more molecules) and Chamber A at a lower pressure (fewer molecules) opening a valve allows molecules to transition between chambers and the pressure will equalise depending how long the valve is open and how many molecules transfer.

The best part about discussing vacuum is that we are literally and metaphorically talking about nothing ;-)

:)

When is MicroSoft gonna make something that doesn’t suck??? When they make a vacuum cleaner !

B^)

And many farm equipment manufacturers build a product they won’t stand behind…

a manure spreader.

[rimshot!]

Good stuff. While I’ve just totally put it off for nearly a year, there’s some vacuum physics stuff I’ve been wanting to experiment with. I thought I’d have to skip a mechanical pump and go straight to a diffusion style, but that was me just assuming I needed a harder vacuum than might actually be necessary. At the time of my initial interest, I was looking at those cookware-style degassing chambers – I recall them being fairly cheap. I am liking the idea of using jars, especially since they could be pretty cool for classes where the participants get to take the items home (just have to consider a robust and easy way to seal them before removing them from the pump. If I can find an area at my makerspace that would like to host the equipment, I should just bite the bullet and buy a small rig to donate.

One thing I was wondering about those el-cheapo single-stage pumps: can they be attached in series somehow to improve (er, reduce?) their suckiness?

As with his Lighthouse presentation, this one was unique and interesting. Thanks again Alan!

“One thing I was wondering about those el-cheapo single-stage pumps: can they be attached in series somehow to improve (er, reduce?) their suckiness?”

Depends. Read up on pump curves, try to find the curve of the pumps (datasheet) and then determine if the second one actually gives any improvement, or if the first one just sucks “through” it.

Staging of pumps is used for reaching higher vacuums, but in that case the pumps are different types with different curves.

Tying a bunch of cheap mechanical pumps together will get you to a 100 mTorr vacuum faster, but not to a lower pressure. The fluid in the chamber switches from a viscous flow regime (particles interact with each other), to a molecular flow regime (no interactions) in the 10s of mTorr range. Different pumping technology is required to go lower.

A diffusion pump only works in the molecular flow regime, so a roughing pump is required to get from atmospheric pressure to a crossover pressure where the diffusion pump can be used. This same roughing pump can then be used as a backing pump for the diffusion pump.

You’re on the right track with choosing a diffusion pump. They are cheaper than other pumps (cryo, turbo, ion) and are very simple (no moving parts). Get a good rotary vane roughing/backing pump (Leybold Trivac for example) since they can be rebuilt and will take years of abuse if properly maintained. It’s worth spending money there to avoid any hassle. A hackerspace with a CNC and a welder shouldn’t have much trouble building a decent chamber. I’ve seen DIY chambers made with aluminum tooling plate, viton o-rings, and a welded stainless internal frame. An advantage here is that walls can be removed to machine holes for ports/windows. Remember, it’s only 14.7 psi pushing on the walls, so it doesn’t need to be over engineered unless you need really flat surfaces. Focus on keeping things vacuum clean and your chamber should work (dish soap, then acetone, then methanol works great or dish soap, then isopropanol).

Yates mentions gauges, and does go over the types, but there are some really compact setups available that do everything. The Granville Phillips/Brooks Micro Ion Atm series is not too expensive on ebay (~$100), and they work great for everything. They are basically 3 gauges in one and go from atmospheric to UHV.

If you are interested in thin films, “Materials Science of Thin Films” by Ohring has a decent short primer on vacuum systems plus a lot of info on thin film deposition and metrology.

Hope this helps get you going. A hackerspace vacuum system sounds like a great way to introduce people to a huge part of physics and engineering.

Thanks for the suggestions!

I didn’t expect displacement pumps to go beyond a certain quality of vaccum, but was wondering more about whether 2 $50 units in series would pull a vacuum similar to a $250 unit. Though thinking back about the experiments I’d like to eventually do, I would need something to pull a harder vacuum. Then again, since I’d need a displacement pump anyway, I could start off with experiments possible in that realm until I could add a diffusion pump.

That gauge you recommended looks like a quality part. It never ceases to amaze me how cheaply lab-grade equipment can be purchased on the used market.

Can anyone recommend how/where to get one of those furnaces Alan mentioned? Searching for “muffle furnace” on the usual places (Ebay, Aliexpress) yield few results that cost <$1k